TOPPING, Virginia — Oysters are essential to keep our waters healthy, and they've been around for 15 million years. But the Chesapeake Bay's once-abundant harvest has drastically depleted over the last century. Two cousins in Topping, Virginia are determined to help them make a comeback.

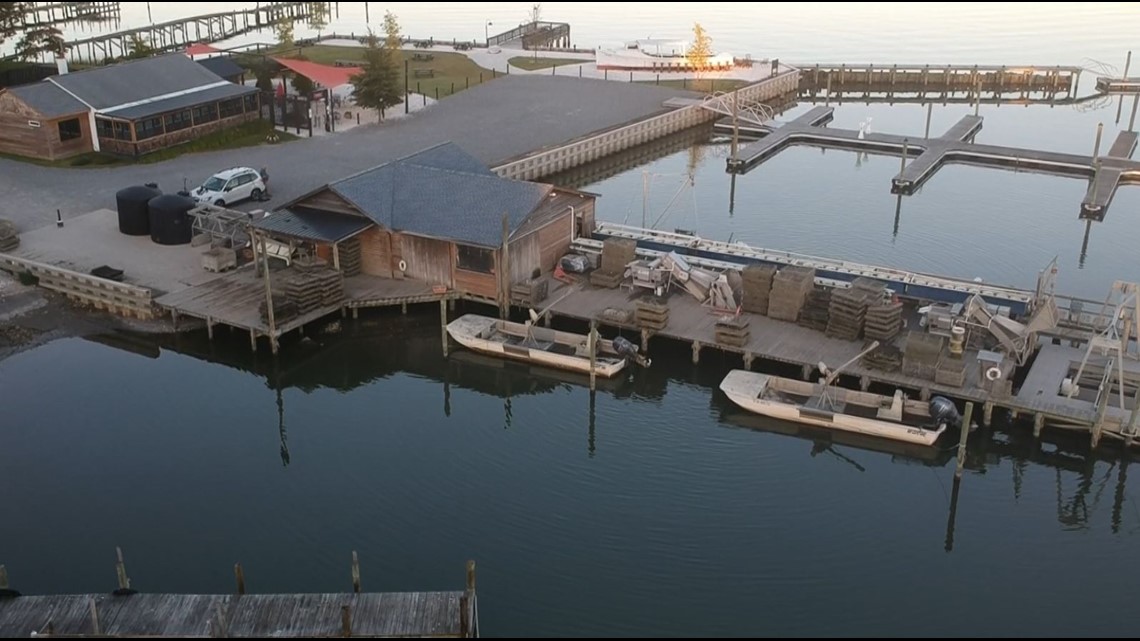

Ryan and Travis Croxton have been running the Rappahannock Oyster Company for the last 20 years. The company is a gift passed down from their grandfathers, but the younger Croxtons have honed in on a new mission: protecting one of the region's most cherished resources.

The Vision

"We’re not taking from nature, we’re actually adding to it," Ryan Croxton said.

How’s that work? The short answer: the oysters the company ships out aren't wild, they're farmed. That means they're still grown in the same waters, but in protected enclosures and with a broader vision.

"The idea is while we’re farming these, the wild population has a chance to rebound," Patrick Oliver, one of the company's oyster farmers, said.

Oliver is responsible for helping the bay's native oyster population rebound from decades of disease and overharvesting that have winnowed down the Chesapeake’s oyster harvests to less than one percent of what they were in the 1800s, according to the Chesapeake Bay Foundation.

"Without the oyster, you don’t get these effects that allow for a healthy ecosystem," Oliver said.

That's because adult oysters filter up to 50 gallons of water a day. Each.

With fewer of these natural cleaners, all aquatic life was at risk in the Chesapeake. But thanks to oyster farming, that’s starting to change.

RELATED: Report: Groundwater near the Chesapeake Bay is contaminated with harmful cancer-causing chemicals

The Operation

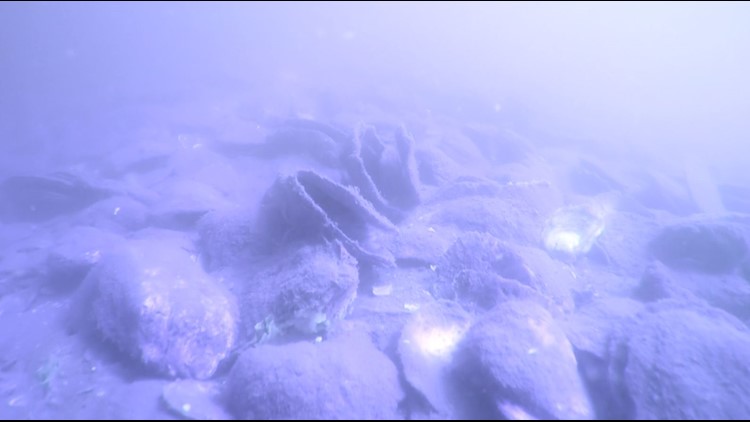

Rappahannock’s operations unfold across 150 acres of the Chesapeake. Most of the action happens beneath the surface.

That’s where more than 10 million oysters of all different sizes live in nearly 5,000 cages lining the bottom.

Oyster farming in the Chesapeake Bay

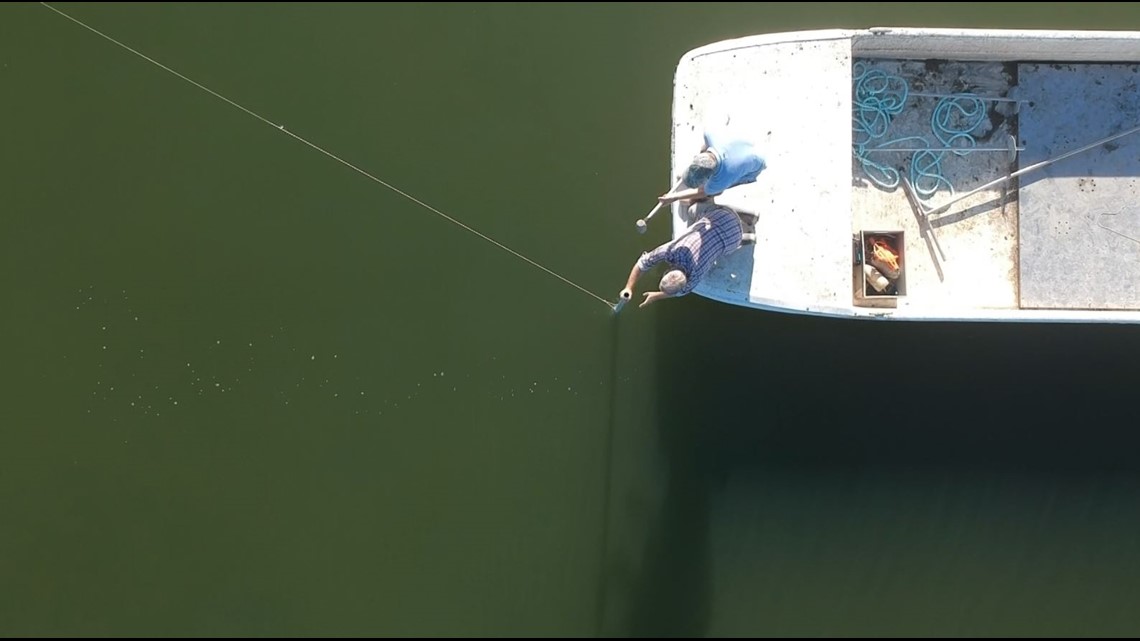

The oysters arrive from hatcheries tiny and full of potential. By the time they leave, they are a lot bigger and a lot tastier. What happens in between is a complex process that’s closely monitored by Oliver and other staff.

The oysters are grown, removed, sorted by size and left to grow a little more, all over the course of a year and a half. Rinse and repeat until they’re ready for market.

Oliver says it’s a high bar to get picked. Only the best oysters make it to market and to Rappahannock’s own tasting room, right across the street.

To the well-trained tongue, Oliver says it’s obvious these oysters are from the Chesapeake.

The Impact

After twenty years spent carefully honing their farming techniques, the Rappahannock Oyster Company has a lot to show for it. They put out between six and eight million oysters a year.

Some years, farm production in the Chesapeake actually exceeds the wild oyster harvest. For Croxton, that’s a sign of success.

"We’ve definitely seen an explosion of interest both in consuming oysters and in growing them so I think it’s here to stay," Croxton said. "I wouldn’t call it a fad 20 years later.”