KENT NARROWS, Md. — Boat captains up and down the mid-Atlantic shorelines are preparing to hibernate for the cold, bleak and unproductive winter months. It's a welcomed respite following a grueling summer of twice-a-day fishing tours, reduced numbers due to COVID-19 and less profit compared to bountiful seasons in the past.

It's an unforgiving job. Only the relentless, experienced and most passionate captains will survive, let alone thrive. This year saw even fewer Black captains among their ranks than in the past.

African-American watermen have seen their numbers in a precipitous decline with few remedies available to turn back a changing tide; one once rich with black culture.

The first African-Americans saw the idyllic waters of the Chesapeake Bay in the 1600's. The history of this bountiful bay is stocked with enormous contributions from its Black inhabitants. They have been watermen, boat builders, cooks and oyster harvesters.

Right now, there's a concerted effort underway to protect this endangered species of Black watermen and women.

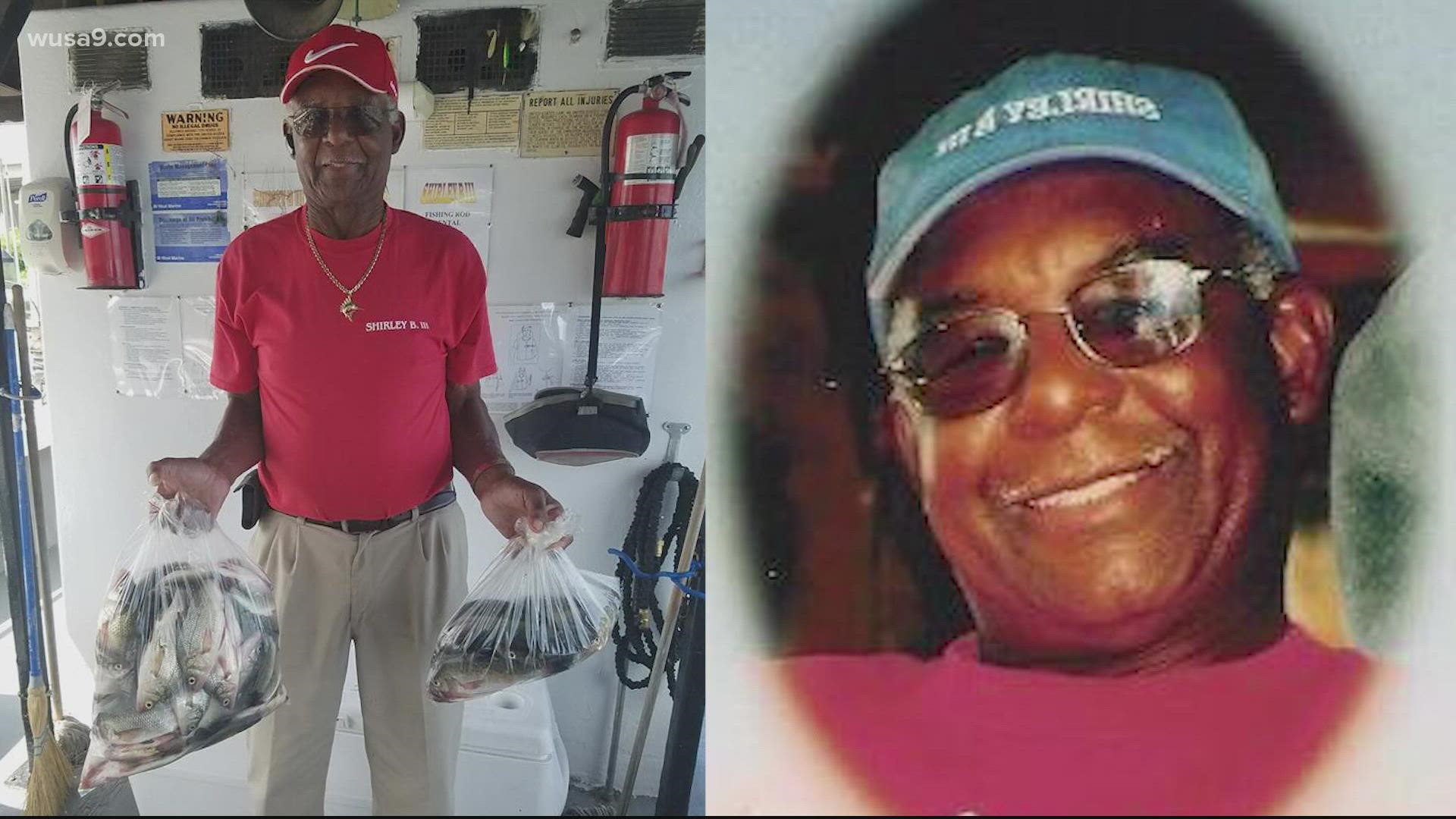

Captain Montro Wright still operates his head boat, the "Shirly B III", out of a slip in Kent Narrows, Maryland. At 84, he is the oldest living Black captain on the Chesapeake Bay today.

"I started coming out with my dad when I was five going on six," says his 63-year-old son Lamont Wright, who operates his own head boat, 'Off Da' Hook', from Kent Narrows.

Now, the younger Wright is baiting hooks to try and lure the next generation of Black captains onto the Chesapeake to prevent his legacy and that of his ancestors from dying in the Bay's brackish waters.

"My goal is to make this a living legacy," Lamont Wright said. "For the Black watermen, and the Black captains of the Chesapeake. If somebody doesn’t step up and do something right now, there will be no Black captains."

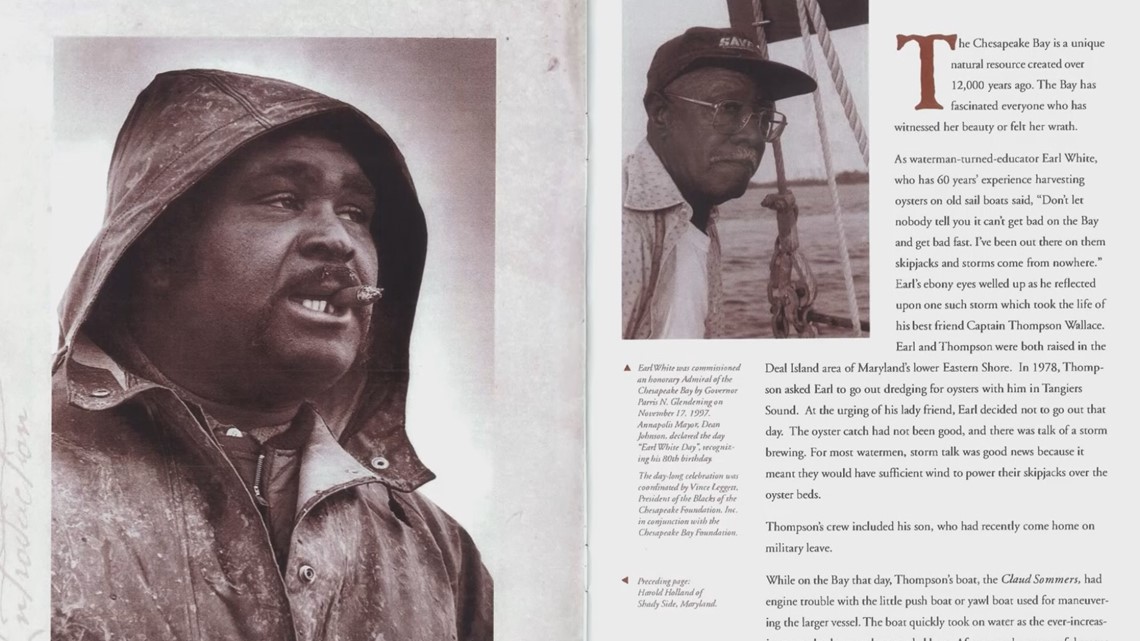

Historian Vince Leggett wrote the book on black contributions to the Chesapeake Bay. Literally.

"African-Americans are an amphibious body of people," the author of Through Ebony Eyes: Preserving the Legacy of Blacks on the Chesapeake' said. "The black watermen of the Chesapeake Bay have the same kind of impact as the Tuskegee Airmen, the same impact as the Buffalo Soldier. But their story is just beginning to be told."

An honorary Admiral of the Chesapeake Bay, Leggett's book is a fascinating journey through the turbulent triumphs and tribulations of African-American history on the Bay.

"Preserve the history and heritage of the Bay," Leggett said. "To show that we weren’t just crab pickers and oyster shuckers, but owners of seafood processing plants. Owners of boats. Sailmakers. Owners of five-star restaurants."

Cedric Cooper is destined to be one of the next black captains of the Chesapeake. It's in his DNA.

"This is something I feel I have no other choice but to get into," says the 27-year-old as he releases the ropes and sets the 'Off da' Hook' free from its dock.

Cooper is Captain Montro Wright's grandson and Lamont Wright's son. He said his grandfather’s work ethic has steered him towards to his destiny.

"He’s worked too hard," Cooper says. "He’s worked so hard that he had my father work extremely hard to become the business owner that he is."

And Lamont Wright is ready to hand over the reins.

"I want my son to go ahead and take over and enjoy and have a good way of life," he said.

Imani Black has spent the past five years as a commercial oyster farmer. Not once, she says, did she ever encounter another woman of color while in the profession.

"This isn’t something we should just talk about," Black said. "We should be active with our engagement."

Black took her own advice. In 2020, she launched a nonprofit organization called Minorities in Aquaculture, or MIA. Quite appropriately, she says, minorities in aquaculture are MIA -- missing in action.

"I was meant to be on the water, I was meant to be an oyster farmer," Black said. "And I was meant to run a nonprofit."

Black's goal with MIA is to entice and enlist African-Americans back into the aquaculture professions.

"It’s not just about internships and mentorships," she said. "It’s about career development skills. Really giving people the tools to create a viable and sustainable career on their own terms."

Together, Black, Leggett and the Wright/Cooper father-son trio are hoping to carry on a proud tradition of Black men and women on the Bay for another 400 years and beyond.