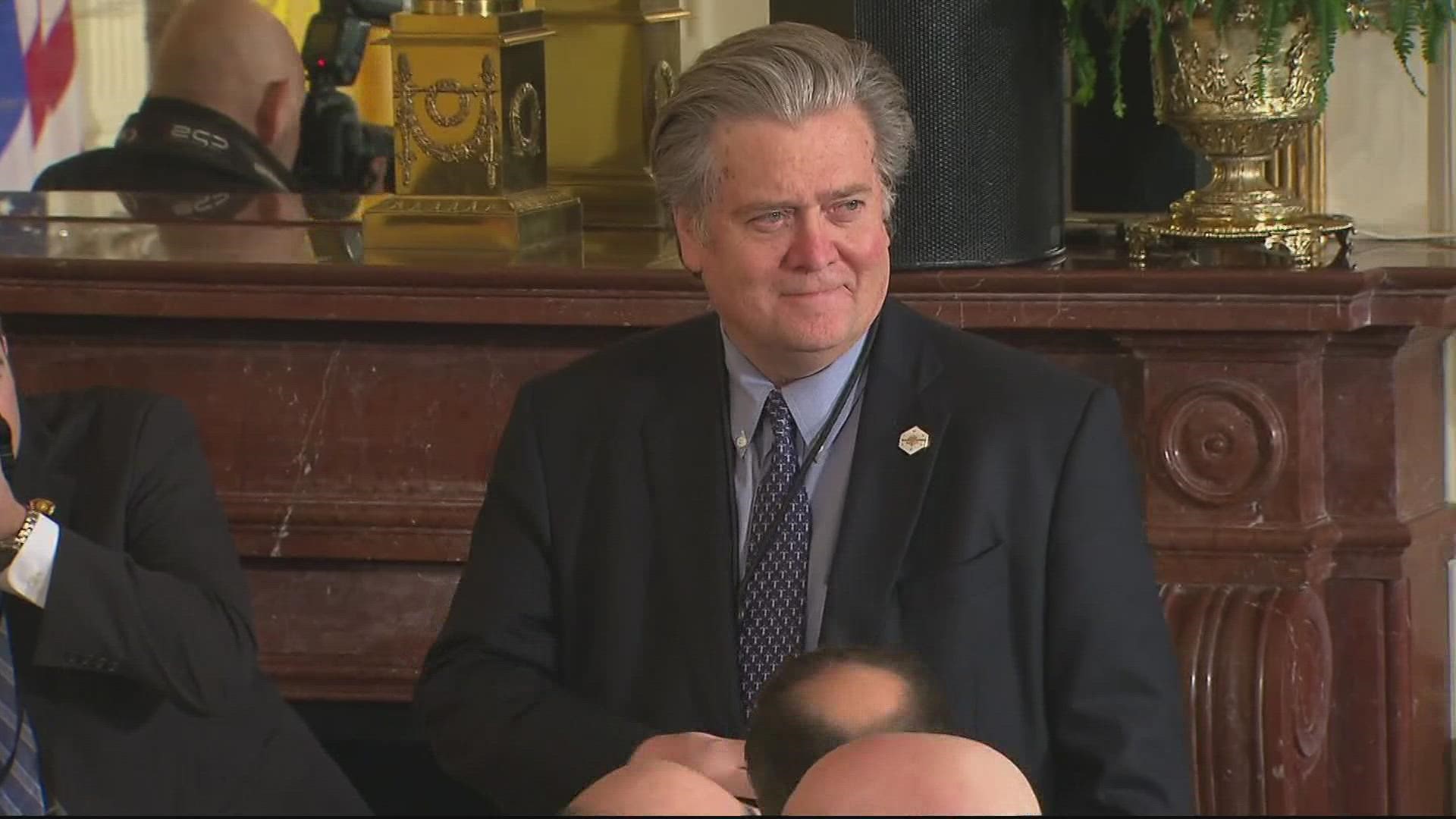

WASHINGTON — A jury convicted Steve Bannon of two counts of contempt of Congress on Friday — finding the former White House senior adviser had willfully defied a subpoena when he refused to testify or provide documents to the January 6th Committee in October.

Bannon, 68, is the first person in former President Donald Trump’s close orbit to face criminal charges in a case connected to the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol Building. Bannon served as CEO of Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign and worked for eight months in the White House as the president’s chief strategist and senior counselor. He left that position in late 2017 and had been a private citizen for more than three years by the time of the attack on the Capitol.

According to a letter from committee Chairman Bennie Thompson (D-MS) attached to his subpoena on Sept. 23, 2021, Bannon remained connected to Trump and others working to overturn his loss in the 2020 presidential election. The committee subpoenaed testimony and documents from Bannon about any communications with Trump in the days before Jan. 6 and also his alleged presence at the Willard Hotel “war room” on Jan. 5 “during an effort to persuade Members of Congress to block the certification of the election the next day.” The committee’s letter also requested information about Bannon’s communications with the Oath Keepers, Proud Boys, InfoWars host Alex Jones and multiple lawyers who were advising Trump, including Rudy Giuliani and John Eastman.

The subpoena required Bannon to submit documents by Oct. 7 and to appear for a deposition by Oct. 14. Assistant U.S. attorney Amanda Vaughn told jurors on Tuesday, the first day of testimony in his trial, that Bannon had defied that order.

“The defendant decided he was above the law and decided he didn’t have to follow the government’s orders like his fellow citizens,” she said.

FULL TRIAL COVERAGE

Bannon maintained in letters to the committee and publicly that he was shielded from testifying by executive privilege, which he claimed Trump had invoked on his behalf. Though his former attorney, Robert Costello, was prepared to testify about that, the claim remains disputed — both the committee and Trump attorney Justin Clark told investigators there was never an invocation of executive privilege for Bannon. As recently as a July 9 letter to the committee offering to testify, accompanied by a letter from Trump purporting to waive executive privilege, Bannon was continuing to claim he was prohibited from providing materials to the committee because of the former president. Prosecutors have called those letters an 11th-hour attempt to avoid trial. Vaughn stressed that to jurors again on Friday in her closing arguments.

“Ladies and gentlemen, when it comes to the defendant’s sudden offer to comply? You know what’s really going on there,” she said. “The only purpose of those letters was so the defendant could come in here and use it to convince you a deadline was not a deadline.”

The committee voted to refer a contempt vote for Bannon to the full U.S. House of Representatives on Oct. 18, and the House voted to refer him to the Justice Department on criminal contempt charges three days later in a 229-202 vote. Nine Republicans joined all Democrats in voting for the referral. Bannon was indicted by the DOJ in November on two criminal counts of contempt of Congress, both misdemeanors.

On Friday, after a four-day trial that saw only two witnesses called to the stand, a jury found Bannon guilty of both counts. Jurors deliberated for approximately three hours before returning the verdict. At sentencing, set for Oct. 21, he’ll face a minimum sentence of 30 days in prison and a maximum sentence of one year in prison on both counts.

‘The Misdemeanor from Hell’

Bannon, a former investment banker and film producer, began carving out a niche for himself as a right-wing firebrand in 2007 when he co-founded the far-right website Breitbart News. Since 2019 he’s hosted his own podcast, titled “War Room.” That persona was on full display in November when, walking out of his initial hearing at the D.C. District Court, Bannon promised to go on the offensive and make his case “the misdemeanor from hell” for the government.

“They took on the wrong guy this time,” Bannon said.

To mount that offense, Bannon brought on an unusually high-powered team for a misdemeanor case. He hired Evan Corcoran, a former assistant U.S. Attorney who served in the same office now prosecuting Bannon, and David Schoen, a civil rights lawyer who represented Trump during his second impeachment trial before the U.S. Senate.

Corcoran and Schoen launched an aggressive campaign on Bannon’s behalf, asserting multiple defenses in a flurry of motions ranging from executive privilege and reliance on Office of Legal Counsel opinions to an effort in June to subpoena House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-CA), Thompson and other members of the January 6th Committee and House Democrat leadership. In court, Schoen argued the case was not, as the government described, about a simple issue of noncompliance. Schoen said the subpoena against Bannon and his indictment for failing to comply with it was evidence the committee was “politicizing” the Justice Department and aiming it at Democrats’ enemies.

Those defenses hit a brick wall last week when Nichols ruled all the government needed to prove Bannon willfully defaulted on his subpoena was that he “deliberately and intentionally” failed to appear or provide documents. Relying on a binding 1961 D.C. Circuit Court decision in Licavoli v. United States – a contempt of Congress case involving former Detroit mobster Peter Licavoli – Nichols said Bannon would be barred from presenting most of his preferred defenses, including that he’d relied on his belief he was shielded by executive privilege or on advice from his attorney, Costello. Nichols also quashed all of Bannon’s subpoenas to House Democrats, finding they were shielded from compelled testimony by the U.S. Constitution’s Speech and Debate Clause.

Nichols’ ruling left Bannon’s defense with only the narrow option of convincing jurors he’d failed to appear because he believed the dates on his subpoena were not fixed, but rather flexible.

Bannon and Costello had initially planned to testify at trial. After Nichols’ ruling, however, both decided not to take the stand. Bannon’s defense team closed on Thursday without calling a single witness or presenting a case to the jury.

Instead, Corcoran used his cross-examination to try to paint the government’s chief witness, January 6th Committee general counsel Kristin Amerling, as a Democrat operative who had issued the subpoena to Bannon out of a partisan vendetta. Corcoran asked Amerling repeatedly about who picked the dates on Bannon’s subpoena – dates he referred to variously as “arbitrary” and “placeholders” – and questioned her about whether she’d seen Thompson sign the document. In his closing arguments, Corcoran implied, without evidence, Thompson’s signature might not have been “legit.” That prompted an objection from prosecutors that was quickly sustained by the judge.

Corcoran also focused much of his questioning about what he described as Amerling’s “relationship” with assistant U.S. attorney Molly Gaston, who served as co-counsel for the prosecution. Under questioning, Amerling said they had overlapped on a committee chaired by former Rep. Henry Waxman 15 years prior and were in the same book club – although Amerling said she hadn’t attended for more than a year and couldn’t recall the last time she and Gaston’s paths had crossed. Vaugh hit upon what she described as the irrelevancy of Corcoran’s questions during her rebuttal argument.

“They want to talk about book clubs!” Vaughn said. “I don’t know what courtroom Mr. Corcoran was in, but all I learned from that testimony was that Ms. Amerling and Ms. Gaston are book club dropouts.”

During closing arguments, Corcoran said Amerling and the committee wanted to “make an example out of Steve Bannon.” That’s why, he told the jury, they wouldn’t accept Bannon’s claim of executive privilege and they wouldn’t “negotiate” with him about a one-week pause in the contempt vote.

Vaughn said on rebuttal the defense wanted to talk about book clubs and politics and who picked the date on Bannon’s subpoena to distract jurors from Bannon’s ongoing decision not to comply with his subpoena.

“You’re not missing anything. This is not difficult. This is not hard,” Vaughn said. “There were two witnesses because it’s as simple as it seems.”

Bannon’s team was expected to quickly appeal the verdict. Schoen spent much of his time during the trial preserving objections for the record about the “willfully” standard Nichols applied in the case and the judge’s decision not to allow Bannon to call in Thompson and other Democrats for questioning on the witness stand.

We're tracking all of the arrests, charges and investigations into the January 6 assault on the Capitol. Sign up for our Capitol Breach Newsletter here so that you never miss an update.