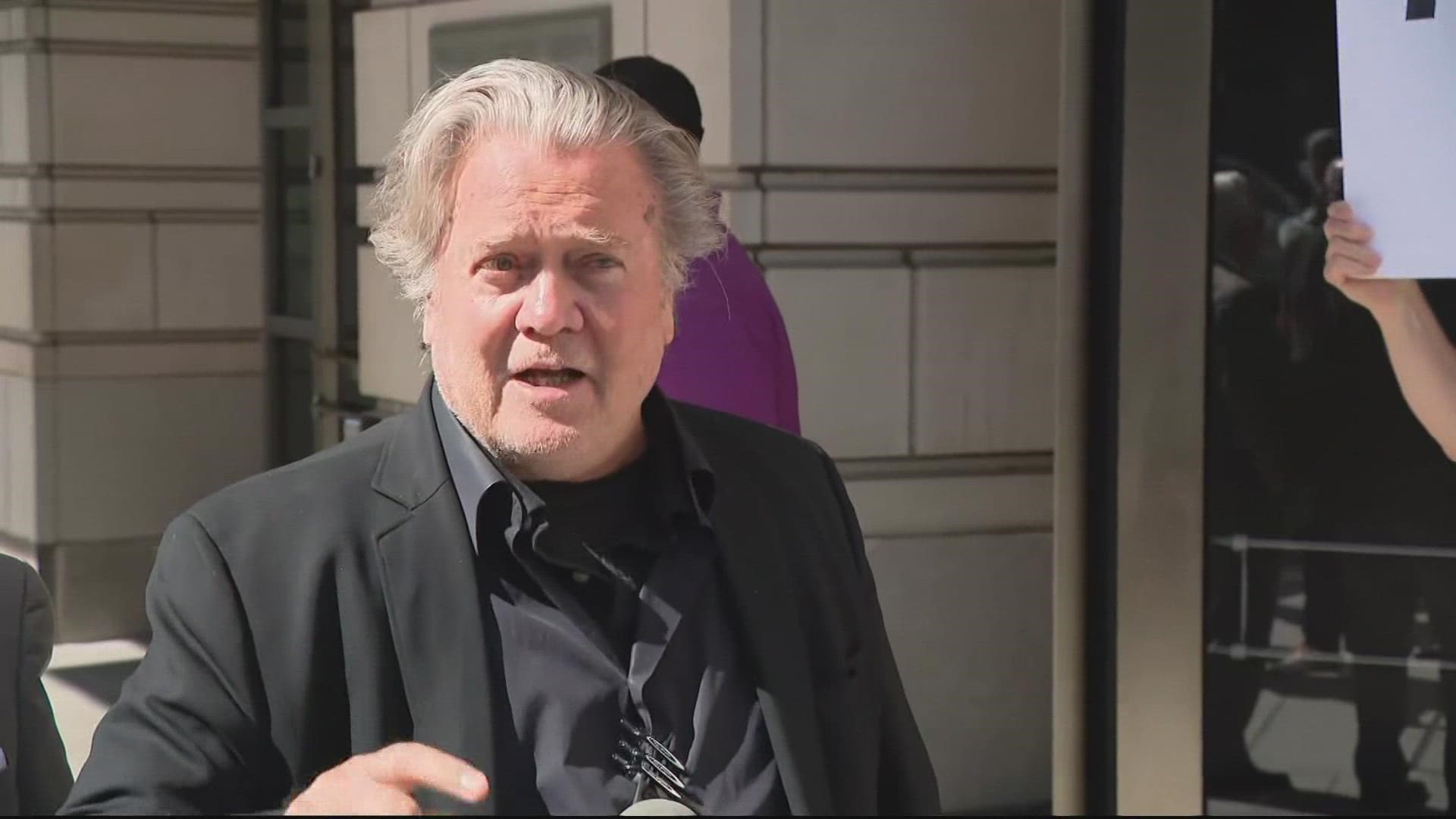

WASHINGTON — After months of legal wrangling and fiery public statements – and hours of last-minute arguments in court – Steve Bannon appeared for the first time before a jury Tuesday to face two misdemeanor counts of contempt of Congress.

Bannon, 68, is accused of failing to appear for a deposition and failing to turn over documents subpoenaed by the January 6th Committee last October. Following his indictment in November, Bannon promised to make his case the “misdemeanor from hell.” But last week the judge overseeing his case, U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols – who was appointed to the federal bench in 2019 by former President Donald Trump – quashed subpoenas his attorneys sent to House Democrat leadership and barred him from telling jurors he ignored a subpoena from the committee because the former president invoked executive privilege on his behalf.

In their opening statements Tuesday afternoon, prosecutors told jurors the allegations before them were straightforward.

“This whole case is about a guy that just refused to show up,” assistant U.S. attorney Amanda Vaughn said. “Yes, it’s just that simple."

Vaughn said Bannon received the subpoena, through his attorney Robert Costello, in late September compelling him to appear to testify and to turn over documents about his alleged involvement in the Jan. 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol Building. In a letter attached to the subpoena, both of which were submitted into evidence Tuesday, Select Committee Chairman Rep. Bennie Thompson (D-MS) highlighted Bannon’s alleged presence at the Willard Hotel “war room” on Jan. 5 “during an effort to persuade Members of Congress to block the certification of the election the next day.” The committee also wanted to question Bannon about comments made on his podcast on Jan. 5 in which he promised “all hell is going to break loose tomorrow” and to examine any communications with the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, Three Percenters and InfoWars host Alex Jones. Jones spoke at a rally on Jan. 5 and has said he was in communication with “Stop the Steal” organizers, but has not been charged in connection with Jan. 6.

Vaughn said Bannon, who served for a time as Trump’s 2016 campaign manager and then as a senior adviser in the White House, knew he had to comply and chose not to.

“The defendant decided he was above the law and decided he didn’t have to follow the government’s orders like his fellow citizens,” she said.

Bannon is being represented in the case by civil rights attorney David Schoen and Evan Corcoran, a former assistant attorney with the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia – the same office now prosecuting Bannon. Barred from presenting their preferred line of defense, Corcoran’s opening statement suggested instead Bannon’s team will seek to cast his subpoena as politically motivated. Corcoran described members of the House of Representatives as “perpetual candidates for office” and said more than 200 of those members had voted not to refer Bannon to the Justice Department.

“Ask yourself, is this piece of evidence affected by politics?” Corcoran said.

Bannon’s defense team did not note that nine Republicans joined Democrats in the 229-202 vote to refer him for contempt of Congress, or that all of the nay votes were from the GOP side of the chamber.

Corcoran also told jurors “no one believed Steve Bannon was going to appear on Oct. 14” – because, as he said, congressional subpoenas involve a negotiation and accommodation process. That argument will be central to Bannon’s primary line of defense, which is that he believed the date on his subpoena was not fixed, but rather “malleable.”

After opening statements, prosecutors called the first of two witnesses expected to testify in the government’s case: January 6th Committee general counsel Kristin Amerling. Amerling spent approximately an hour on the witness stand testifying about the basics of how Congress and congressional subpoenas function before Nichols called a recess for the day.

Jurors were instructed to return to court at 9 a.m. Wednesday for the rest of Amerling’s testimony.

Off to a Contentious Start

Tuesday morning was consumed by arguments over excluded testimony that had largely been litigated in a hearing last week – as Nichols pointed out by reading a transcript of his ruling from that hearing. The most contested point was a set of letters between January 6th Committee Chairman Bennie Thompson and Bannon’s attorney Robert Costello in October of last year.

In the letters, according to a motion filed by defense attorney David Schoen, Thompson told Bannon his position on executive privilege was “inappropriate” and without an “legal basis.” In its exhibit list, the government described the letters as Thompson “rejecting noncompliance and directing Defendant to comply.” Prosecutors want jurors to see the letters because, they said in court Tuesday, they show “no reasonable person” would have received them and believed Bannon’s congressional subpoena was “malleable.” Bannon’s attorneys wanted the letters kept out of court because Nichols barred them from subpoenaing Thompson and other members of the House Democrat leadership.

“Mr. Bannon has a full story for why he didn’t show up,” Schoen said. “All of these defenses and his story of the case have been barred by the court at the government’s request.”

Schoen argued if the letters were allowed in, the defense should also be allowed to introduce excluded evidence about why Bannon thought he did not have to respond to his subpoena by the date on it. That could include evidence his attorney, Costello, told him the date on his subpoena was not set in stone because of ongoing efforts by the committee to enforce it.

Assistant U.S. attorney Amanda Vaugh flatly rejected that argument in court.

“That’s like someone who willfully doesn’t pay their taxes for 10 years can’t be charged with a crime because the IRS, once they find out, tries to get them to file their taxes,” she said.

Nichols eventually ruled the letters were admissible in their entirety, although a ruling on a second set of letters will wait until after Amerling’s testimony. Those letters – one from Trump, claiming to waive executive privilege over Bannon, and a second from Bannon offering to testify before the committee – were made public with a little more than a week to go before Bannon’s trial was set to begin. Prosecutors have described them as an effort by Bannon to avoid consequences and as “a different kind of contempt and obstruction.”

We're tracking all of the arrests, charges and investigations into the January 6 assault on the Capitol. Sign up for our Capitol Breach Newsletter here so that you never miss an update.