A year in the life of a Capital Gazette shooting widow

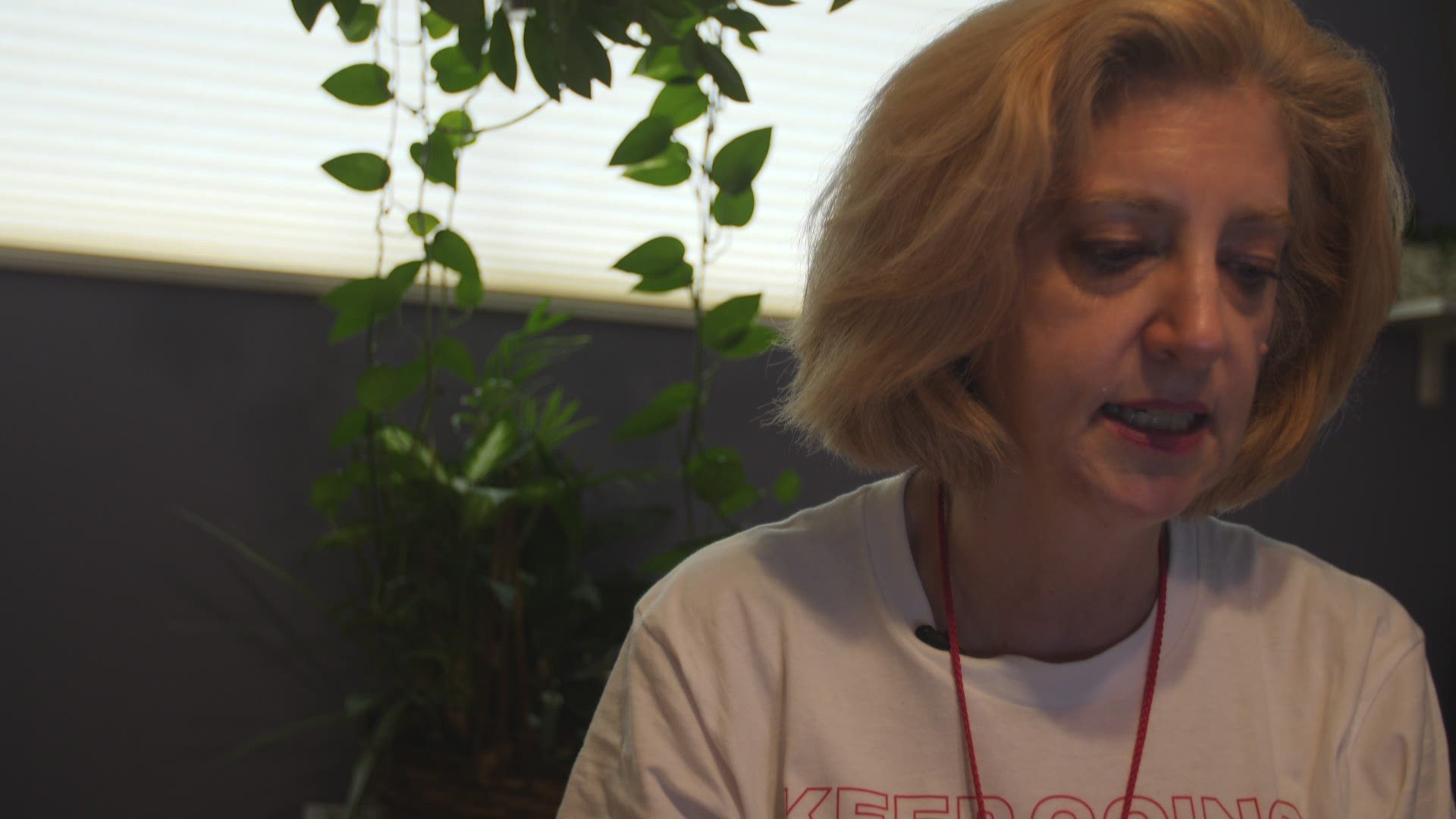

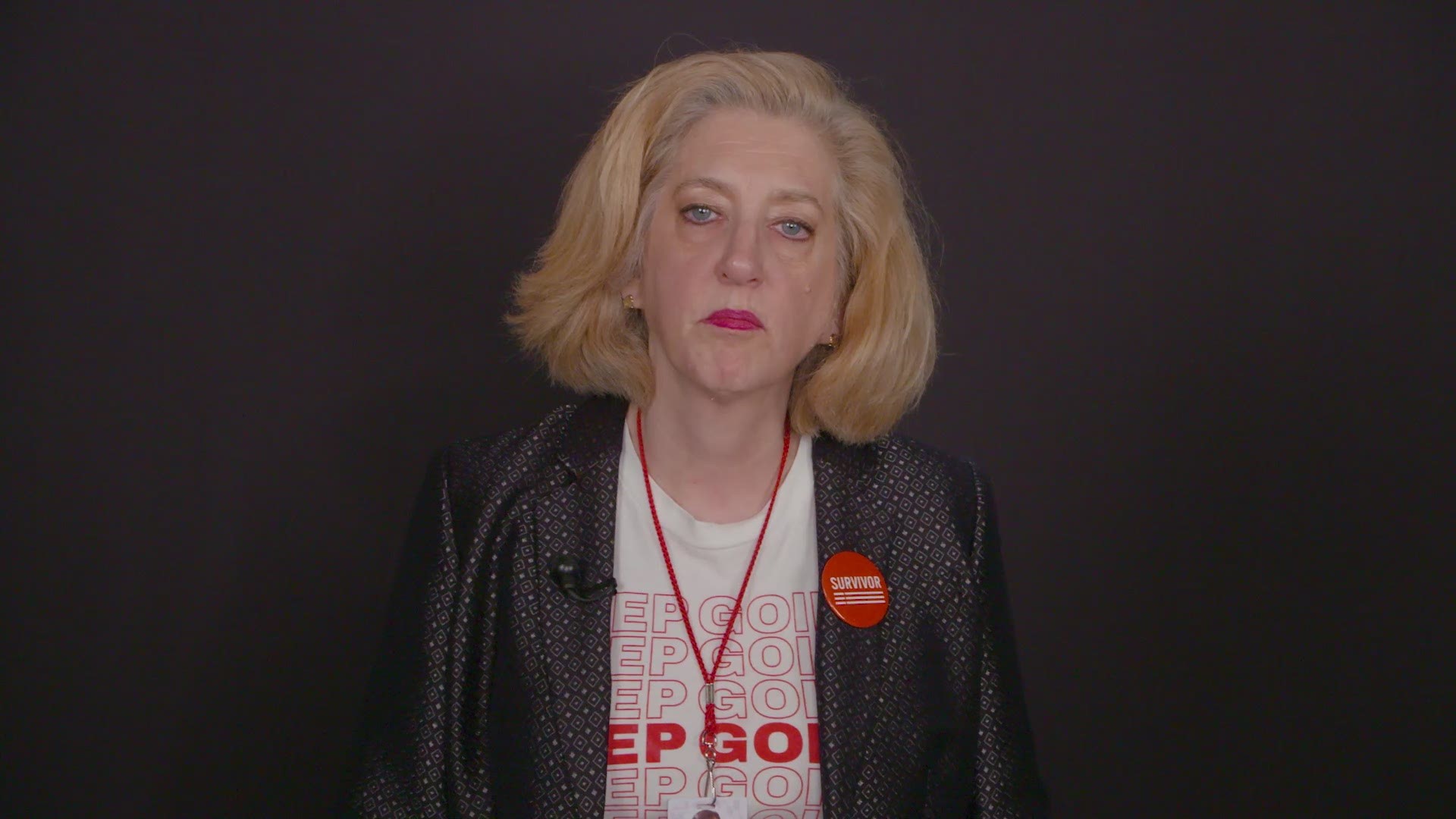

Andrea Chamblee was married for 33 years to John McNamara. Until the day she took on a label she never wanted: another mass-shooting trauma survivor, trying to make sense of the senselessness amid an empty home.

In March, when she got back from Havana, Andrea Chamblee figured it was time to have a talk with her husband.

She pulled into the carport in the Subaru Forrester, the one they bought in 2003. She leaned over the gear shift, into the passenger seat. She began to speak.

“Did you like Cuba, John?” Andrea asked. “Are you proud of me? Am I doing the things you want me to do?”

No answer.

The only sound came from the car speakers: "I'll be seeing you in all the old places."

Damn. John's sister sang that song. At the memorial. Andrea began to weep.

She walked inside, dumped her swimsuits and vacation clothes in the washer at the back of a cluttered basement, where their bikes still sit beside one another seat-side down.

Andrea microwaved a hot pocket, laptop at her side.

She journaled on Facebook. By 11 p.m., she turned off the television, lights and walked upstairs.

It’s been 10 months, but she still gets in on the left side. Her side, so she doesn’t disturb his gray house slippers, which remain as they did on June 28, 2018, the morning John McNamara left for his job at Annapolis’s Capital Gazette newspaper.

"He's not really a bathrobe and slippers guy, but I didn’t know what to get him one birthday – and I got him the slippers and he said he really liked them," Andrea said. "So, you know, they’re there when he comes back."

She is certain she's seen him in ghostly form. Mental-health professionals call this "defensive delusion," comforting the mind to believe someone is alive when someone is dead. Either way, coping with the reality your life partner of 33 years is never coming home burrows deep into the hole, forcing Andrea to ask John the most difficult question of all:

“Why didn’t you listen to me? Why didn’t you work from home that day?”

Why did he have to die and send her spiraling into what felt like her own afterlife -- a hellish world of multiple 75-mile round trips to Annapolis and back, where she tells her story and hopes beyond hope of moving Maryland lawmakers to do something about gun violence besides sending her form letters of recognition and achievement, as if living after your husband is killed is something she wanted to accomplish?

Why does her last love letter to John have to be 312 pages, a posthumous book about D.C. basketball she's finished and found a publisher for -- on top of her regular full-time job as a government lawyer? Why couldn't John have written his own last chapter?

Damn, she keeps thinking. This is what all those other spouses that lost the love of their lives felt. This is the hollowed-out feeling coming home and poking your head in an empty office den, where the urn of your husband's remains sits next to a press-row portrait of him, on the happiest night of his sports writing career, atop a bookcase.

This is what it feels like to try and continue to make your life meaningful after all the meaning is gone, how to search for specks of old joy in a junkyard of sorrow and, really, how to hold two things that don't belong together inside yourself and make a whole person again.

Some days Andrea can't do it; the grief is still too much. And the one-year anniversary since it it all happened is but a month away.

Stepping into the Silence

There were five of them shot and killed in the newsroom – John, a longtime sports writer for the paper who’d been moved inside the office, knower of all things basketball in Maryland and D.C.; Rob Hiaasen, the editor and a columnist for much of his career; Rebecca Smith, a recently hired sales assistant; Gerald Fischman, the editorial page editor and a beloved Gazette employee of 25 years; and Wendi Winters, a community correspondent and mother of four, whom the six survivors in the office credit with saving their lives after she charged the attacker with a trash can and recycling bin.

Those five casualties don’t include Rebecca Smith’s fiancé or the three wives and the eight children. They don’t include the six co-workers who hurdled bodies on the floor and the co-workers not in the office during the shooting, who came back to an active crime scene to put out a paper for the next day. Or the law enforcement officers and EMTs, who could never un-see the dead on the newsroom floor.

Andrea joined them all in mourning, joined America’s fastest-growing support group – trauma survivors of a mass shooting, the broken people left behind to walk into the silence of sorrow.

"There's a before and after to my identity now,” she said. “What I really want to say is ‘I am the wife of John McNamara. But there's something about that 'W' word that doesn't come out quite right. I have to say, ‘I am the widow of John McNamara.’ It's changed everything. It's changed my identity, people's response to me, it's changed what I think of myself. It’s a big life change.”

Christmas cards still hang on her living-room wall. Two plastic-potted poinsettia plants from December sit cracked and dried in front of the glass door leading to the patio. It is now May.

Except for bills and other necessities, she's given herself permission to get things done when she feels like getting them done. She rarely goes in John's office, where the urn of his remaining ashes sits atop the bookcase, competing for space and time with a portrait of John looking up from the Georgia Dome’s press row on April 1, 2002 – the night Maryland, his alma mater, won its only men’s national basketball title.

Since July, the covered patio they shared after long work days has been vacant. The top of the antennae on the ancient SONY two-band radio John listened to Nationals and Orioles games on is covered by a cobweb.

“I haven't been able to sit out there,” she said. “Not last summer and not since. Sometimes I come home and I say, 'I hate my house. I hate my house.' But I am going to hate a new one, too."

Before and after dusk are the hardest hours, when the grief deepens and she just feels defeated, sad, lonely. At least once a day she cries, “because I miss John, and I miss my lost vision of our future together. Today, for the first time, I cried just because I'm so tired.”

And yet, on her dining-room table rests her proudest accomplishment since John’s death – a 500-page draft of a manuscript. He had worked on his most ambitious project for 13 years, a book titled, "The Capital of Basketball: A History of D.C. Area High School Hoops." Andrea finished it for him, writing a bit of each chapter between 1900-2000, the years chronicled. She captioned all 178 photos and struck a deal with Georgetown Press to publish a 312-page book in November.

Yoga and fitness were part of her life before last June. But they’ve taken on a greater meaning the past 10 months -- half healing balm, half distraction. A temporary tattoo, “Warrior,” is stenciled on her right biceps, and "Keep Going" is spelled out on her left biceps. They are so well-defined, her friends call them "Michelle Obama arms." Turning 58 in March, Andrea can hold a plank – an abdominal/core strength exercise involving maintaining a position similar to a push-up for the maximum possible time – for three minutes.

Balancing grief with getting through daily life, she refuses to acknowledge her own resolve and courage to move forward.

“It really doesn't feel like courage, that feels like the wrong word," she said. "To me, I think of courage as when you have the choice between danger and safety to help someone, and you choose danger. I don't have a choice."

She will get up again tomorrow because, "not getting out of bed in the morning doesn't seem to be an alternative that I can accept. As much as I can use eight hours of sleep in a row, I just… don't know how else to respond to something like this except to beat it at its own game. I am going to beat this tragedy at its own game."

Back from the Abyss

Andrea dubbed the wandering existence of mass shooting trauma survivors, "The Zombie Apocalypse." Becoming a widow, she said, has made her more intuitive in ways she never wanted.

RELATED: 'They were innocent journalists gunned down': Benefit concert held for Capital Gazette victims

When two survivors of the 2018 Parkland, Fla., high school shooting and a father of one of the 26 murdered at Sandy Hook Elementary in 2012 committed suicide in March, unaffected and non-grieving Americans wanted to know why, almost needing a cable-news panelist to mouth the words, “Survivor’s Guilt,” if only because it helps them understand.

Andrea didn't need to hear anything; she knew. She keenly understood the depths of grief, how the unthinkable becomes almost rational. “We know too much about the brain now to blame them for being selfish or awful people,” she said.

"I know I am afraid to think about [suicide]. I know I am afraid to go to that edge, but it's easy to get close to that edge and to say this isn't the life I wanted. But if I hear that voice, I know that it's a lie. That it will get better. I just don't know how long it's going to take."

Last month was another disenchanting, 18-hour day at the Maryland state legislature, where Andrea has partnered with #MomsDemandAction and other groups committed to gun violence prevention.

Legislation that would require background checks on private sales of rifles and shotguns passed the House and was awaiting a third and final vote in the Senate before it moved to Gov. Larry Hogan’s desk. It never made it. Several senators cowered in the face of a group called, "We Will Not Comply," led by a Wicomico County Sheriff convinced his landowners needed to keep their pump-action shotguns and other assorted assault rifles to protect their property.

"There is a danger of getting angry at the wrong people," she says. "I'd like to find something to get angry at. I think that the shooter would be a convenient target for anger. But the world will always be full of mean and dangerous people. I find myself angry at the people who could have prevented it and didn't do anything to prevent mean and dangerous people from getting dangerous weapons."

RELATED: 'He shot people all around me': Capital Gazette article gives readers chilling firsthand accounts

Maryland became the 18th state to abolish the death penalty in 2013; Andrea wouldn't have asked for it anyway.

"If they could guarantee me a swap that if this guy died and John could come back, I think that would be a terrific swap and I would take it in a heartbeat. I would insist on it. But if you are telling me to add one more body to the body count of all of this, I don't see how that helps anybody."

She went to see John for the last time in early July. Her cousin entered the morgue first. After seeing John, she motioned to Andrea from behind a curtain that it was OK to come inside.

"I didn't know where he had been shot. I didn't know what I would see," she said.

John's body was wrapped in a massive ice pack, some four feet wide. He was on his back on a table and there was no hand or arm to hold. She later learned from investigators he was shot in the shoulder and the chest and his clothes were used for evidence.

Closure, she said, is a term used by "the very naïve."

"I don't believe closure exists," Andrea said. "Closure doesn’t exist outside of books that dangle it like it’s something you can achieve if you can just walk through the right hoops."

When a well-intentioned person told her recently that the hole and the trauma will always be part of her -- and the key was to learn to fill it up with healthier things -- she managed a half smile.

"I hope that's true," Andrea said."Sometimes I wonder, though, if it just stays a hole."

#AbsurdityoftheDay

The letter from MetLife and the Office of Federal Employee Group Life Insurance, or FEGLI, came later last summer. She had provided the death certificate and the manner of John's death, but it wasn’t enough. They could not compensate Andrea for John's policy, the letter read, unless she provided a police or coroner’s report, both of which have been under seal since the investigation began.

When Andrea called, the insurance company representative told her that most shootings are done by the romantic partner.

"You have to prove you were not the shooter," he said.

It wasn’t until an embarrassed vice president had Googled her name and called back 15 minutes later to apologize that they had agreed to pay the claim.

"But what about the families they can't just Google? What happens to them?” she thought.

That indignity began Andrea’s calling on Facebook, daily posts that went beyond journaling and toward something more profound – #AbsurdityOfTheDay. Sometimes they were an historical record of her grief; but they also highlighted the tone-deaf and callous ways America handles grief as a nation, ranging from a corporation's coldness to the family member that says or writes something so heinous the person grieving never wants to hear from them again.

"#AbsurdityoftheDay: John's name is on the (phone) bill because (they) won't let me put it in my name. (Funny, I think my name is on all the caller IDs, including his own phone.) His name is also on the gas and the lawn service bills, and every time one arrives, I still gasp."

"For most people, they don't have that experience of people trying to make sure their loved one is remembered," she said, summing up societal attitudes about mourning. "People want their loved one to be forgotten. They want them to get over it. They want them to move on more quickly and they want to know why it’s taking them so long."

The post-a-day goal was modest, Andrea said.

"To write one thing a day so if the fog ever lifts I will be able to look back and try to remember how I feel," she said. "Although part of me thinks I won't want to remember how I feel."

September 22, 2018 · #AbsurdityoftheDay: "To the person who sent me the message of all the ways I have failed in the last 3 months, and how I might perform satisfactory reparations at your earliest convenience, you forgot to say please. Or thank you."

Facebook made itself a major target with its automated videos, complete with cheery music under Andrea’s “great” July, “happy memories” of 2018. Interspersed with a photo her and John were funeral processions and mass-shooting headlines.

They are not all serious – she caught their wedding-gift microwave on fire trying to make popcorn, melting the inside and throwing the smoldering unit in the carport before the smoke alarm went off. But taken as a living document, Andrea illustrates how little frustrations morph into big issues, sometimes destroying her faith that things would be better.

Take a fruitless trip to Annapolis two months ago:

February 28 · #AbsurdityoftheDay: "Don't confuse my tears for weakness. The gun extremists here today can follow me into the building. They can hack my accounts. They can take my picture in the hallway and post it online ... probably with my address. But don't confuse my tears with lack of courage. In fact, they can go ahead and post my picture on the internet to show their ilk what courage looks like."

Every day, another post, another story of how others experience or deny her her grief. Every day, how the hurt of losing her husband doesn't go away:

April 6 at 2:07 PM · #AbsurdityoftheDay: "I don't see John out of the corner of my eye in his desk chair anymore. I haven't seen his ghostly form outside at the spot

where he always contemplated writing and the moon in the evenings. I saw a fading apparition of him near the place he would usually wait for me to join him outside, but he was walking away, not toward me. I imagined trying to ask him why he couldn't have worked at home that day, but he kept getting further away."

Moving Forward, Stepping Back

She stacked four boxes of his shoes – mostly basketball high-tops (at 56, John still tried to play three times a week) – in front of the television recently. They will be given away to A Wider Circle, which helps those transitioning out of homelessness, fleeing domestic abuse or living without basic life essentials. It's where Andrea donated his summer shirts in July and his winter coats in December.

RELATED: 'What we do is seek justice and truth': Capital Gazette staff named Time Person of the Year

She kept the gray slippers and both wedding rings. The one she gave to him she wears on her right hand. A friend told her she'd be ready to date when she stops wearing hers, "but I can't even take his wedding ring off," she said, shaking her head.

His off-beat humor stays with her, too; little mental-embedded vignettes.

“Hey, Andrea, I just texted you my junk," John once told her, urging Andrea to find her cellphone. She panicked until opening the text to see that John had taken a photo of the couple’s actual garbage under the carport.

"He would do things like that all the time," she said, picking out the shrimp and chopped avocado from two flour tortillas in a takeout box. Andrea ate in the same place she does many nights, next to her laptop computer at her dining room table. She was also organizing 8x11 copies of the book's cover and had "Capital of Basketball" business cards printed up for John, as if he could just show up at a signing one day and autograph a copy.

The tacos were leftovers from the night before. Her married friend of almost 10 years had taken her out for dinner at a brew pub, catching up on life over food and craft beer. After thanking him, via text, she typed, “How’s your wife?”

“Who?” he texted back.

Was he harmlessly flirting? She couldn’t be sure. It was the kind of question she hadn’t asked herself in more than three decades.

"My life is just….crazy right now," she said. "I mean, he's a nice guy and all. But homewrecker is not something I want to add to my resume."

Zena, a friend and power-yoga instructor, helped her create an online dating profile last month. Andrea posted it on an over-50 site. More than 125 men showed interest, which was good for her ego but still felt wrong, as if, odd as it might sound, she was somehow betraying John.

Not wanting to troll hopeful bachelors or upset herself any further, she deactivated the profile and account as April came to a close.

Too many memories, too many conversations with John since he died, to give anyone a legitimate shot yet with her heart.

His voice, she remembered, was "so resonant and full of detail and concern," and his eyes, "were just this amazing blue."

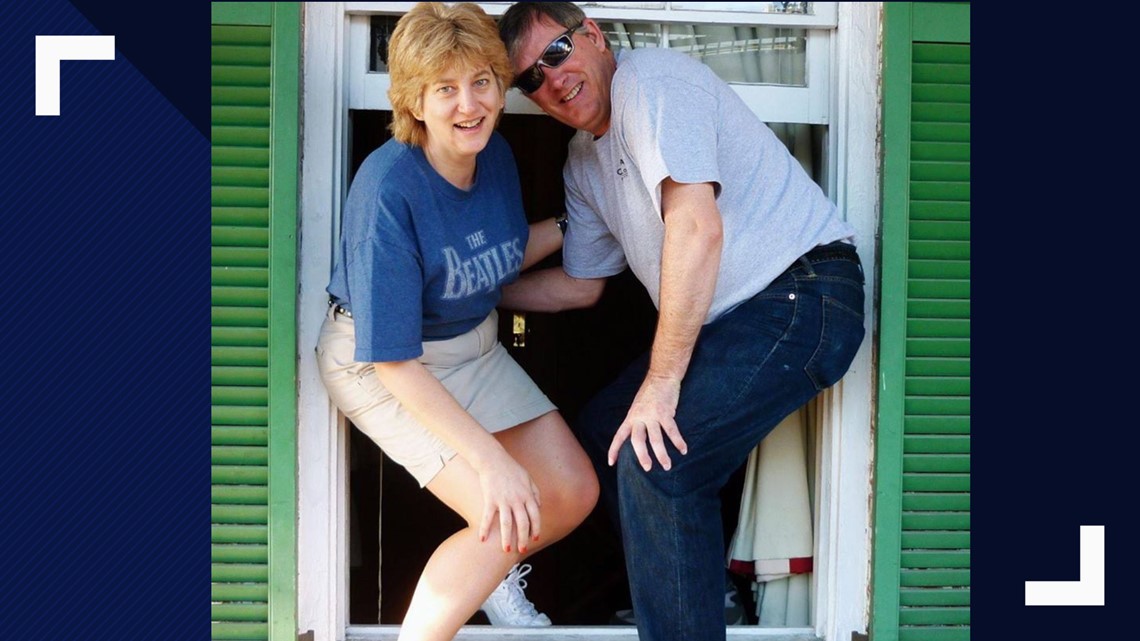

Andrea knew soon after meeting John at Maryland they would end up together.

They were married in 1985 by John’s uncle, a priest, on one of those sun-spackled Memorial Days at St. Louis Catholic Church in Columbia, Maryland. Andrea’s perfect day ended when her mother and other people in the wedding party jumped in the nearby Hilton hotel pool in their full gowns and tuxes.

Within a few years, they wanted kids. They tried for almost two years in the early 1990s and racked up thousands of dollars in debt at pre-modern fertility clinics. They gave up when the medical provider wasn’t sure the amount they would have to write on the check after their last visit.

Andrea was devastated. John was the rock for both in the aftermath, supporting her, accepting their fate and planning a different future.

They lived a frugal lifestyle, mostly because John’s journalism jobs didn’t pay like Andrea’s attorney work. But with only themselves to care for, they were able to see Paris, London, Seattle, Vancouver, San Francisco and whatever Caribbean island they chose each winter – the more magnets on the fridge, the better.

Two days before the shooting, Andrea gave "Alexa" an exact date and asked how many days before their retirement. The answer came out to just over 1,000, less than three years.

"That whole vision of the future is just gone," Andrea said. "I remember at the service, I went to my cousin and I just said, ‘I don't like this movie. Where’s the exit?’ There should be a fire exit somewhere because it feels like this is a fire. And I can’t find it. Maybe I am even in the movie, I can’t tell. I just want to go back to where I was before and there is no exit door. This is it.”

When friends and family call, she doesn’t mince words when asked her state of mind. “Sucks” and “Still sucks" are the go-to replies.

His birthday was hard, but it fell just a month after John was killed; everything was still hazy. Christmas and New Year's were worse. But bookend anniversaries late this month and next – 34 years apart, alternately the best and worst day of her life – will be the hardest.

Andrea hasn’t committed to attend the trial of the man accused of murdering John and his four co-workers. But she’s glad it was moved from June to November, creating some distance between legal proceedings and the one-year mark since the shooting. The only thing she’s certain she doesn’t want to watch is the horror of the security video played in open court.

She has also yet to forgive herself. However inaccurate it sounds, Andrea has taken on a measure of blame for John's death.

John had worked late Wednesday night, June 27, because there was a local election Tuesday night and the returns had come in. On that Thursday, he awoke on just four hours of sleep. "Can’t you just work from home today?" Andrea asked.

The Fourth of July weekend was coming up. He shook his head, no, "I need to go in."

"I just… kick myself for not putting my foot down," she said. "If I had cried and insisted he would have stayed home."

But that wasn't the nature of their relationship. They supported each other in these moments. His credo, in marriage and work, was devotion. "He wouldn’t have not gone in -- that was the devotion he had to journalism and to his co-workers," she said. "It didn’t matter how tired he was, he was going to go."

She pauses, think on it again. No, she's decided she's given herself an easy out: "If I had told him I wouldn't let him go, he would not have gone."

Andrea sits up straight on her couch. John's Maryland press credential mug and red lanyard hang around her neck, the same one she took to Cuba so John could "see" the island with her.

"I always thought that it was possible that I'd never get married when I was in school and grad school and wanting to be a lawyer," she said, voice beginning to crack.. "And I suppose if I stuck with that, I wouldn't be a widow now.

"But if I had the choice of being married to John for only 33 years and never been married to John at all, I want to be married to him for 33 years," she said. "He's the best thing that's ever happened to me."

The tears came and kept coming. "He's the best thing that ever happened to me," she said again, maybe 10 seconds later, with more conviction.

She wiped her eyes with a Kleenex from the coffee table and read her final #AbsurdityoftheDay:

"I don’t want to be brave. I don’t want to be strong. I don't want to be inspiring. I want to be ordinary again. I want to be married to my sweetheart."

The light outside was dying when we left. The house was still.

She had to cook and do laundry, answer emails, revise a draft. Andrea's hardest part of the day was just starting.

Mike Wise can be reached via email at mwise@wusa9.com, on Twitter @MikeWiseGuy, on his Facebook page here and on Instagram.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated Wendi Winters was a mother of three. She was a mother of four.