WASHINGTON — It's green and itchy and it's getting more potent. We're talking about poison ivy, and if you've ever come across it, you know it's one of the worst itches there is.

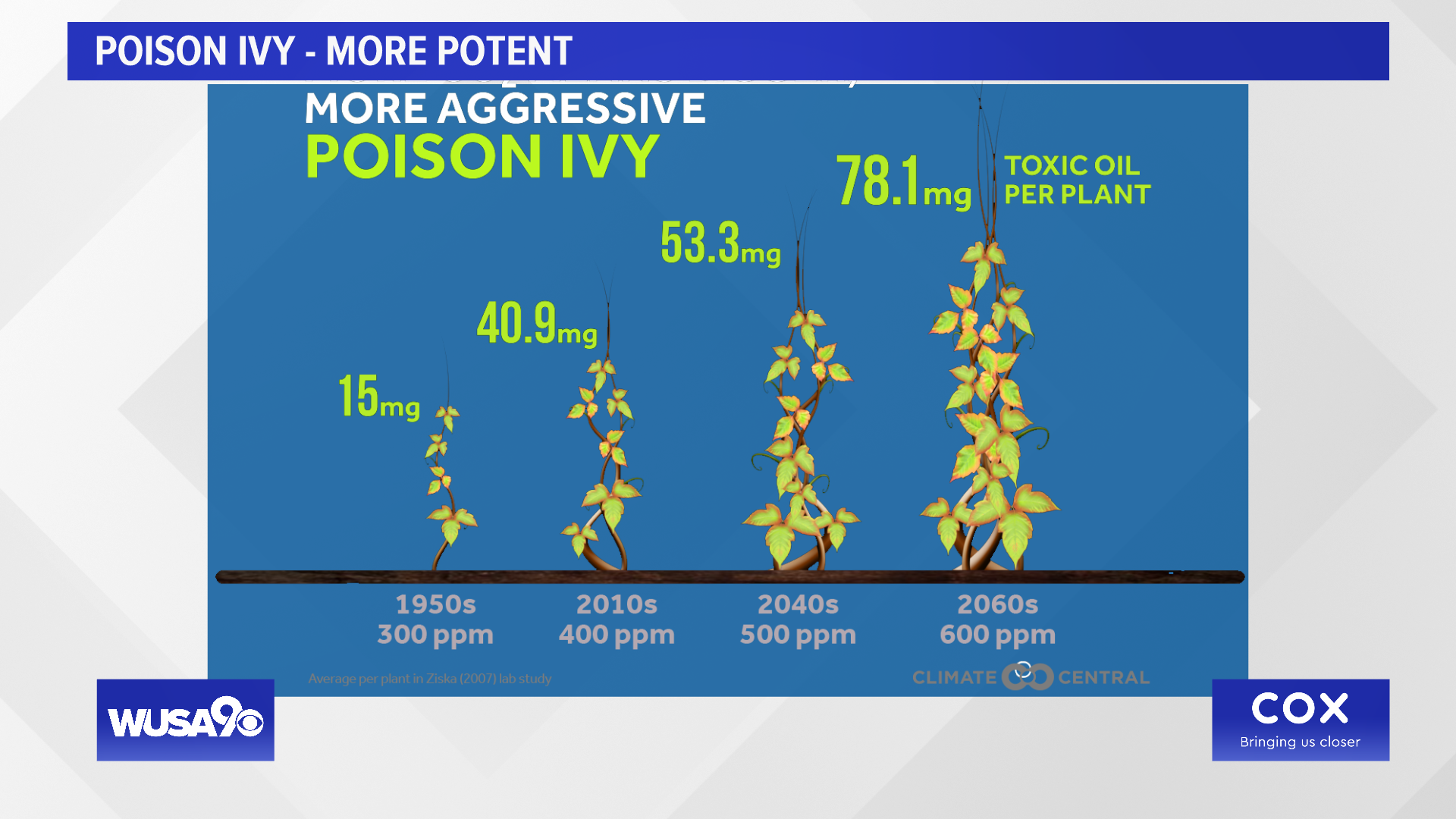

Scientists said that since the 1950s poison ivy is growing bigger and contains more of its' signature toxic oil, urushiol.

From the 1950s until now, the leaf size of poison ivy has doubled, according to Climate Central. An analysis showed that the urushiol in the plants is 173 percent higher compared to the 1950s, from an average of 15 mg per plant to 40.9.mg per plant.

So what's feeding all of this? The main driver is carbon dioxide.

Like most plants, poison ivy thrives on carbon dioxide because it enhances photosynthesis, the process in which plants use sunlight to make food.

Carbon dioxide levels are higher than they have been in 800,000 years according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. NOAA's climate.gov reported that carbon levels in 2018 were at 407.4 parts per million (ppm).

In a 2006 study out of Duke University, scientists found that poison ivy under higher carbon dioxide levels grew at a faster rate and vines were bigger. Also, the levels of the toxic urushiol increased by 153%.

During this 6-year study, researchers exposed the poison ivy to higher levels of carbon dioxide.

Urushiol is what causes the itch when people come in contact with poison ivy.

Some interesting facts on poison ivy: a little goes a long way.

Illinois Wesleyan University stated that only 1 nanogram (billionth of a gram) can cause an allergic reaction. The university wrote that most people are exposed to 100 nanograms of urushiol.

- 500 people could start feeling itchy by the amount of oil covering the head of pen.

- 1/4 of an ounce of urushiol can cause a rash on everyone on earth.

- It is normal for urushiol to stay active on any surface, including dead plants for 1 to 5 years.

- The name urushiol is of Japanese origin, from the Japanese word urushi which means lacquer.

The researchers also expressed concerns that other species in the Anacardiaceae family, including mango, cashew, and pistachio may also cause allergies. Scientists believe that those plants may also become more problematic in the future.