BALTIMORE — Video games and brain surgery are two things not often used in the same sentence. But what if you were able to tweak some of the technology used in certain games to make these tricky surgical procedures safer?

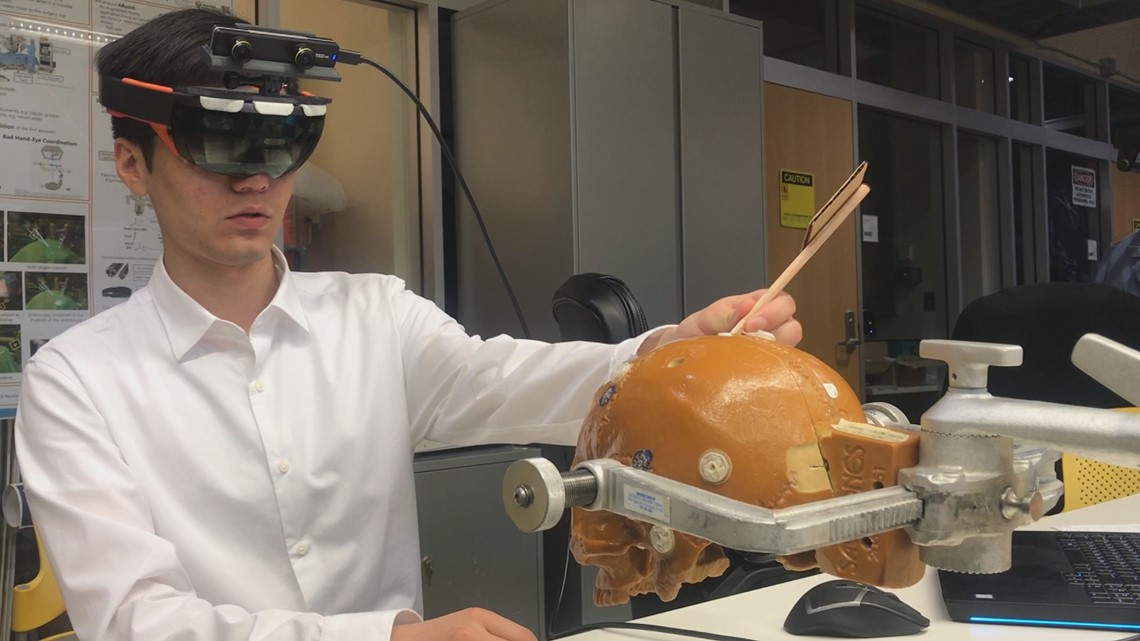

A team of researchers at Johns Hopkins University is creating something to help surgeons perform better. The platform is based on augmented reality and involves taking a virtual reality headset and pairing it for use with image-guided procedures.

"It has cameras, and it has visualizations," said Peter Kazanzides, a research professor in the department of computer science at Johns Hopkins. "The system actually detects where the patient is then overlay medical information on the patient, much the same way a GPS would work to tell you where your car is."

To be clear: It doesn't all of a sudden make brain surgery easier. The AR provides the opportunity to practice. It can highlight certain parts of the brain, showing doctors what they’re looking at, and even put other items into the scene. However, there are a number of challenges.

According to Ehsan Azimi, the leader of the team effort, one of those difficulties is accurately overlaying virtual objects on top of the real scene.

"It is mixed reality, so that involves virtual content and real content... and the very key component of that is to correctly overlay those virtual contents," Azimi said.

"I think the biggest struggle is that it’s much harder than it seems," Kazanzides adds. "I can take an AR headset, put it on, and I can walk the surface of the moon -- so it seems like other things should be easy... but it's actually much more difficult to overlay very precisely on a patient the location of some internal anatomy."

Azimi, who is also a PhD candidate in computer science at the Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering, points out that the team wants this technology to help patients and surgeons. Right now, the project is being used to target ventriculostomy.

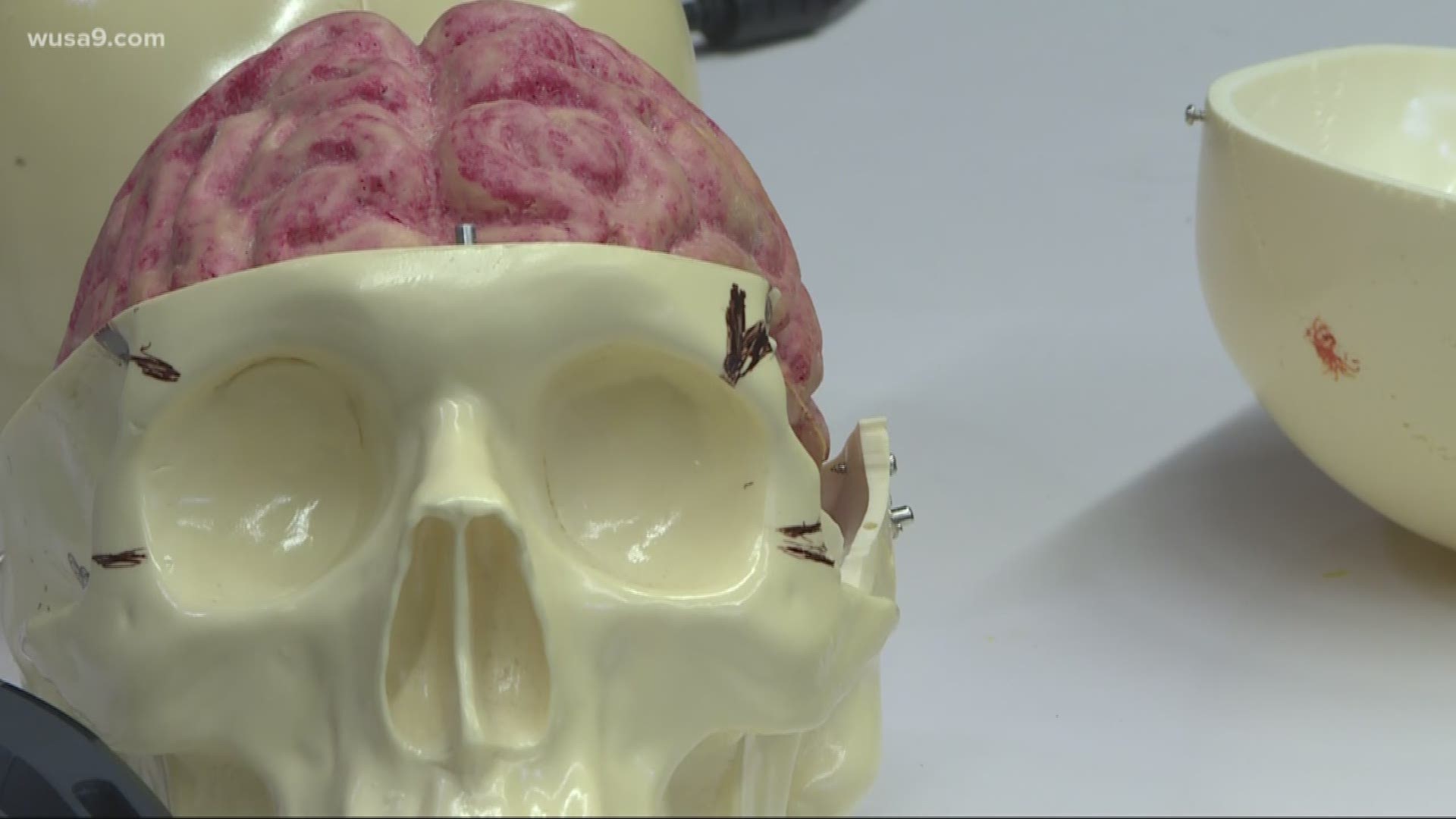

Ventriculostomy is a procedure where surgeons drill a hole in brain and insert a catheter to drain fluid and alleviate cranial pressure. The problem is this procedure can be risky. Surgeons can miss the target because they don’t know exactly what the layout of a patient's head looks like and that can lead to problems like bleeding or infection.

"There is a lot of stress and there is a lot of joy because you feel like you’re doing something useful," Azimi said. "The joy comes from that part, and the stress comes from, 'Wwhat is something goes wrong?' This is not something simple."

The team plans on doing a clinical study on actual patients in about a year, with the hope of eventually turning this platform into a product any hospital can use regularly.