WASHINGTON — Before Washington Football Team legend Doug Williams became the first Black quarterback to win a Super Bowl, he received numerous racist hate mail -- some of which he can still vividly describe decades later.

"I got a box that was nicely wrapped," Williams said of one package he received. "When I opened it up, it was a rotten watermelon with a letter that said 'throw this to the N’s. They can catch this.'"

In 1978, Williams became the first Black quarterback to be drafted in the first round of the NFL draft. He went 17th overall out of Grambling State University, a historically Black college. But over the course of Williams' nine seasons in the NFL, the racist letters continued to come.

"I learned early, when you got a letter without a return address it probably wasn’t a good letter to read," Williams said. "Every time I received a letter with no return address, I threw it away."

Thirty-one years after playing in his last NFL game, Williams regrets throwing the letters out.

"I hate the fact that I did not keep them," he said. "If I had known what was going on with the racial injustice, those letters would have resonated more today than they did back then."

Unfortunately, the hate from outside the NFL was not the only racism Williams would face.

During Williams' first NFL career football game, a reporter asked him, "What were you thinking during the national anthem?" Williams responded that he was counting to see how many Black coaches were on the sideline.

The quarterback was ridiculed the very next day for his comments.

"I met with the head coach and the editor from The Tampa Tribune," Williams said. "They told me 'those kind of statements can’t be said down here,' that the people wouldn’t take kindly to me trying to find out how many black coaches were on the sidelines."

At his start in Tampa, Williams said he was being paid $120,000 annually, which he learned was the lowest salary for a starting quarterback in the league at the time; 12 backup quarterbacks were making more than Williams.

"I was the 54th highest paid QB and I was the starter," Williams said. "My backup on my team made more money than me."

After the 1982 season, Williams asked for a contract extension making $600,000 a year. Williams said longtime Buccaneers owner Hugh Culverhouse refused to pay him what he asked for. According to Williams, he felt the denial was insensitive, especially since his first wife, Janice, had just died of an aneurysm.

Williams stopped playing football completely at that point and went back home to his hometown in Zachary, Louisiana. He became a substitute teacher at a middle school where his brother was the principal.

But Williams couldn't stay away from the game.

When the United States Football League (USFL) was formed in 1983, Williams saw an opportunity to get back into football. The league only lasted three seasons before it folded.

At the time, Joe Gibbs, who was the offensive coordinator for the Buccaneers when Williams was there, was the head coach for the Washington Football Team. Williams agreed to return to the NFL signing with Washington as their backup quarterback.

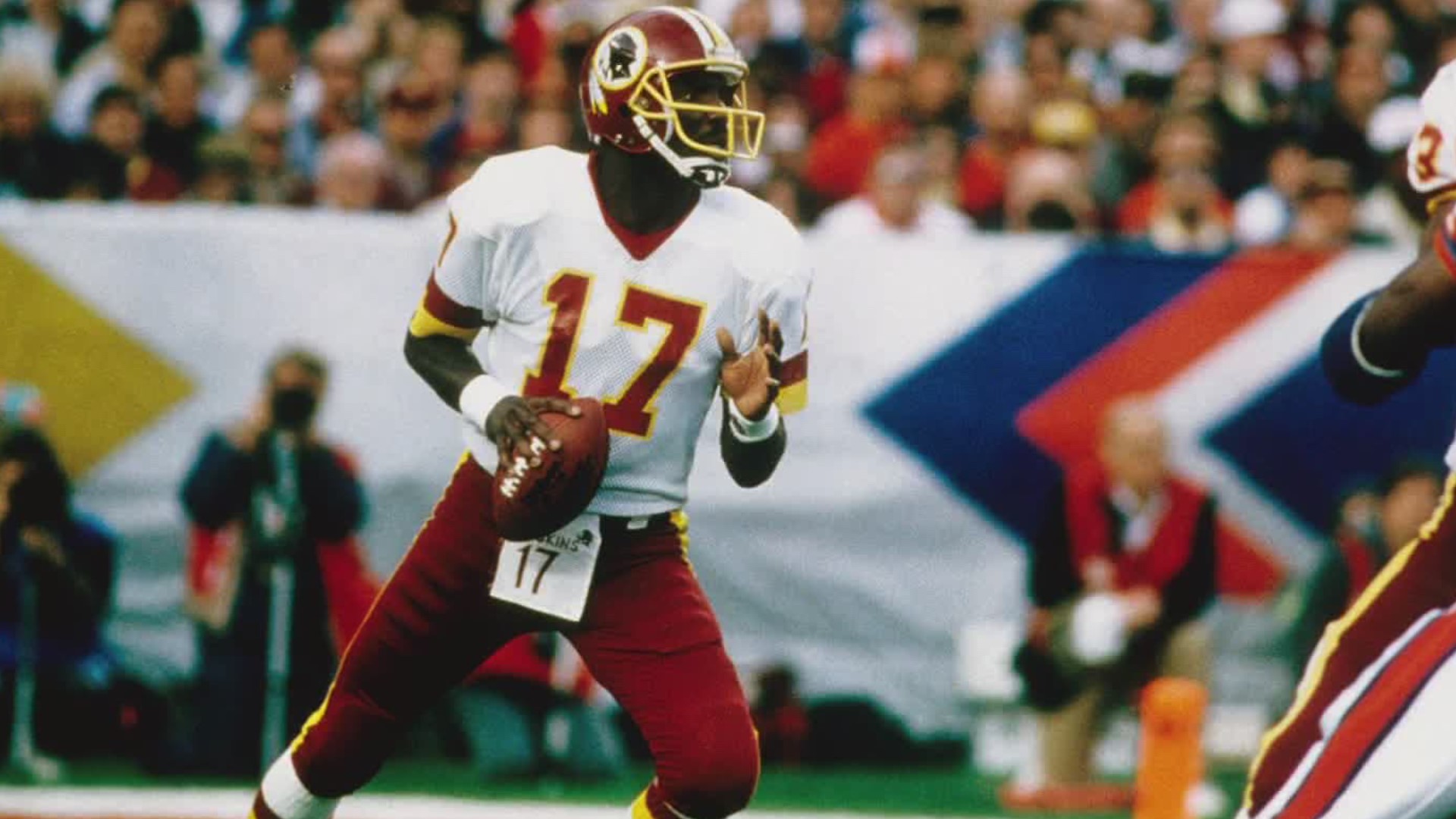

Williams went on to play four seasons in Washington, eventually leading the team to one of their three Super Bowl wins in 1988.

"I felt like I was at the mountain top," Williams said. "Growing up in the south, I didn't think the world was ready for a Black quarterback. This was an opportunity for a Black man and I proved to the world that a Black man can play quarterback on the NFL's biggest stage."

After Williams retired in 1989, he was inducted into the Tampa Buccaneers "Ring of Honor" and Washington's "Ring of Fame." He is now the senior vice president of player development for the Washington Football Team.

"If the people [who wrote the racist letters] looked at the journey and where I am today and remembered what they did in the yesteryears, they would probably say, 'he’s not that bad after all,'" Williams said with a smile.

Williams hopes his journey from seeing burning crosses and members of the Ku Klux Klan knocking on his car window to a Super Bowl-winning quarterback who endured despite facing near-constant racism will inspire others to never give up.

"We can’t stop here, we have to keep marching forward," Williams said. "I hope that when I’m not here, someone will pick up the baton and keep doing it in my name, or keep doing it the way I was doing it."