WASHINGTON — You want to know who Frank Robinson really was, beyond one of the Grand Old Game’s greatest players, beyond the title he will have for eternity – first African American manager in baseball?

He originally turned down membership in the NAACP, figuring the public speaking the organization wanted him to would conflict too much with his career.

But after being traded from the Cincinnati Reds to the Baltimore Orioles in 1966, he and his family could not find housing in many parts of the city. Never mind that he had won the National League’s Most Valuable Player award five years earlier and had already forged a reputation as one of baseball’s most feared hitters and intimidating players. Uh-uh.

White landlords in Baltimore didn’t want black tenants. Simple as that.

He called back the NAACP and joined, becoming active in the Civil Rights Movement, speaking out on racial issues whenever asked, especially on segregated housing and discriminatory real-estate practices in Baltimore.

The dye was cast.

“I wasn’t Jackie Robinson or anything,” Frank Robinson once said in his office at RFK Stadium, downplaying his historical importance, imploring you to take the conversation back to baseball.

“Jackie was the original pioneer. I just wanted to follow his lead, is all. Make things better for black folks. Make things better for everybody.”

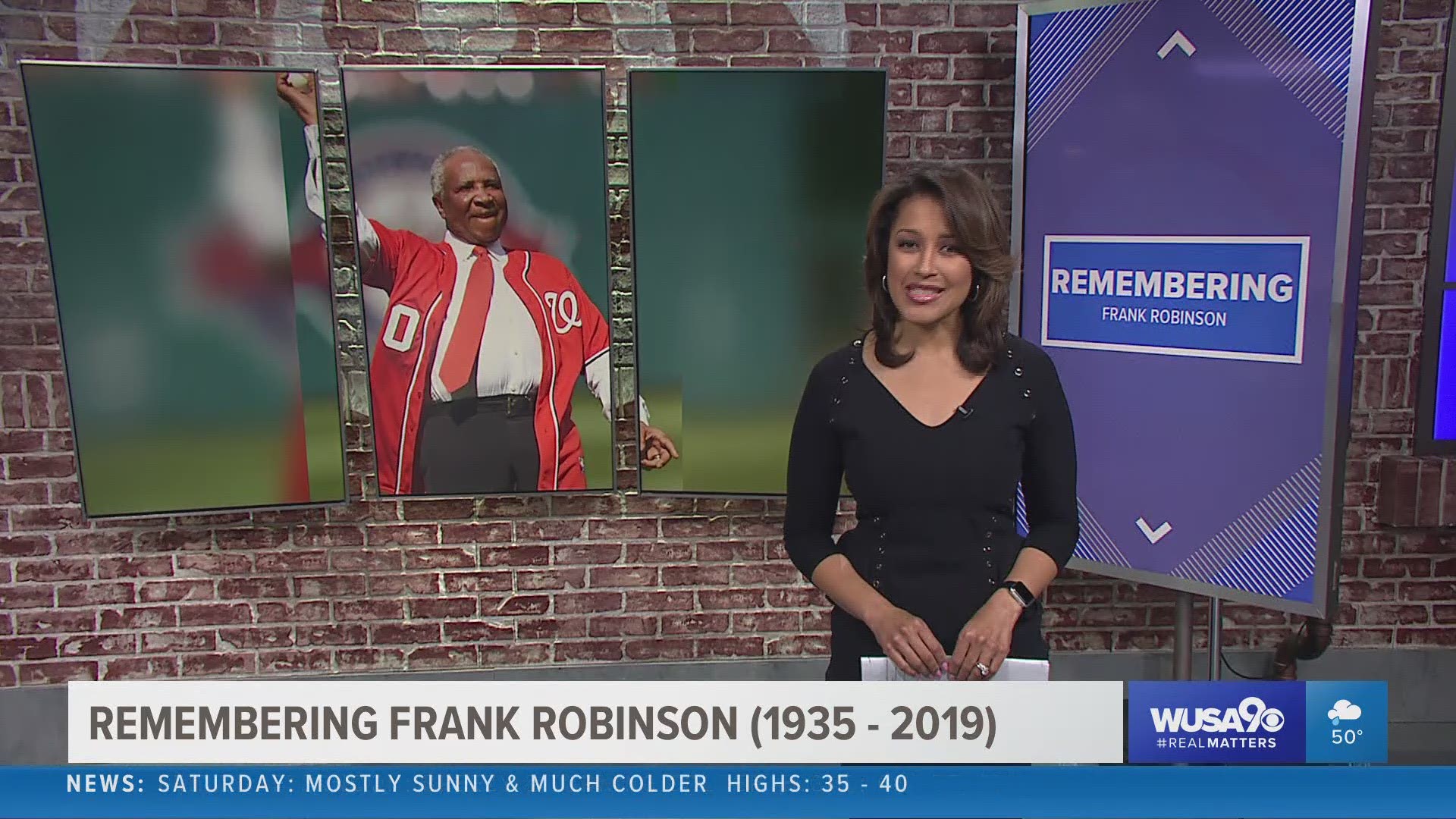

Robinson died Thursday at 83 years old after a battle with bone cancer. Tributes and condolences came from everywhere, his legend emboldening people from baseball and beyond to pay their respects. When you hear the stories and see the numbers, it’s only right.

Some American lives you can’t make up. Frank Robinson’s was one of them. What are the chances of Major League Baseball’s first black manager and the NBA’s first black coach growing up in West Oakland, Calif. together, winning a state basketball championship at McClymonds High School?

Frank Robinson and Bill Russell did that.

What are the chances, of all the Hall of Famers and Hall of Famers to be, just one of them would ever win the Most Valuable Player award in both the American and National League?

Frank Robinson did that, too.

He started his career in 1956, winning Rookie of the Year in Cincinnati. His last game was in 1976. He is still 10th on the all-time home run list with 586. If you exclude four players on that list either connected directly to performance enhancing drugs or banned from baseball because of them, Robinson is sixth on the all-time list.

He is the only player to have hit a ball out of Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium. A sign that read, “Here,” where the home run landed, was there until the stadium was demolished and Camden Yards was built.

After the trade, he eventually rented a home on Cedardale Road in the city’s Ashburton neighborhood. Six months later, he won the Triple Crown (leading the American League in hits, batting average and home runs) and led the Orioles to the A.L. pennant. For the entire 1966 World Series -- the Orioles would go on to sweep the Los Angeles Dodgers in four games -- Baltimore’s then-mayor Theodore McKeldin, the state’s former governor and a moderate Republican, rechristened Cedardale Road, “Robinson Road.”

Before he became the Nationals first manager in 2005, when baseball returned to Washington, he was the only player to wallop two grand slams in one game – at RFK Stadium.

“Frank was one-of-a-kind,” said Mark Lerner, the Nationals’ managing principal owner and vice chairman. “A trailblazer throughout his career, he was steadfast and courageous in his defense of justice and diversity in the game of baseball… He was an ambassador for both the Nationals and the game throughout the city, but was especially fond of sharing stories with children from a nearby elementary school about his time in the big leagues.”

I had no special relationship with him, having covered maybe 20 games he managed for the Nationals. The longest time I ever spent alone with Robinson was 30 minutes at LAX airport in 2009; I was heading back to D.C.; he was coming home from the MLB offices in New York.

Robinson was still bitter the Nationals had fired him three years earlier, how the Jim Bowden-Stan Kasten regime strung him along before dumping -- before anyone knew Bowden and Kasten were just passing through. The Nationals tried to honor him the following season in 2007. But he was too proud for that. He didn’t want to pretend his scars had healed. They finally gave him his day, putting him in their Ring of Honor in 2015.

Tom Boswell, my former colleague at the Washington Post and the dean of American baseball columnists, knew him well – or as well as any person who covered him could. He paid homage to Robinson with some beautiful prose this afternoon.

“For several days, the death of Frank Robinson had been expected,” Boswell wrote. “Editors called reporters to prepare appreciations. But Frank, no respecter of deadlines or demise, didn’t depart on schedule. Some of us who covered him for years enjoyed the thought of Death trying to cope with Frank…’You know you can’t beat me,’ the Grim Reaper says. Frank, silent, just glares and digs in. Robinson didn’t just crowd the plate; he crowded life.’”

There is a classic Robinson anecdote on his Hall of Fame page in Cooperstown: “When asked by a fan how he would pitch to Robinson, All-Star pitcher Jim Bouton replied, ‘Reluctantly.’”

He genuinely lived baseball. There was the night he walked out of RFK Stadium in his manager’s uniform, cleats and all. When Charlie Slowes, the team’s play-by-play announcer, saw him get into his car in the parking lot, Robinson simply rolled his window down: “I’ve got to be back so early tomorrow, why even bother changing?”

Pioneer, unapologetically black in a white-dominated sport, hovering over the plate, daring fire-balling pitchers to hit him (they did, 198 times), salty as hell when things weren’t going his way – heck, Lakers season-ticket holder since the Magic days -- Robinson was a lot of things.

To me, though, his humanity stood out. In 2006, a journeyman catcher named Matt LeCroy started for the Nationals. He had not thrown out a baserunner all year. The Houston Astros knew this and ran on him. And ran on him. Seven steals and two throwing errors later, Robinson took a slow walk to home plate and did what he had to do: pull him in the middle of the seventh inning.

But it was how Robinson reacted afterward that said everything.

"I wasn't trying to embarrass him in any way," he said to reporters. He suddenly welled up. And tears began to come down his cheeks on both sides. "It was just a move at the time, at that moment, I just felt like I had to do it.”

Wrote Barry Svrluga in the Post the next day, “His right hand obscured part of his face. He all but chewed on his pinkie. As he pushed each phrase through his lips, he sighed deeply, all because he asked a grown man to perform a task he is ill equipped to perform.”

Robinson kept crying, feeling for that kid more than he did himself.

I called Matt LeCroy late Thursday night at his home in Belton, South Carolina. In three days he was off to West Palm, Fla., for spring training with the Nationals. He’s the manager of the team’s Class AA Harrisburg Senators.

“Sad day for me and sad day for baseball,” he said through a thick drawl. “I remember the day he pulled me out. Everybody thought Frank was just hard and old school. And he was. But that was a side to him no one expected. I think me and him sort of bonded after that."

“He’d open up to me about his life and the game. Told me I could be a manager one day. We just hit it off. Who’d a thought a redneck from South Carolina and an African American man from California would do that? But we did.”

I asked LeCroy what Robinson taught him about baseball and life.

“I could talk to you all night about all the baseball wisdom he gave me – the responsibility of starters to play every game, all the hitting knowledge you could imagine. But the most important thing was, Frank Robinson taught me that if you don’t care for your kids and your players, you’re not going to have any success as a manager. That moment, when he took me out, he cared about me. He cared.”

The Robinson family has asked that in lieu of flowers, contributions in his memory can be made to the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis or the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

He is survived by his wife, Barbara, his daughter, Nichelle, and baseball.