WASHINGTON — Among the VIP’s of the National Football League that are in Tampa for Super Bowl LV will be a lifetime Washingtonian that grew up in Maryland who is a powerful force in professional football.

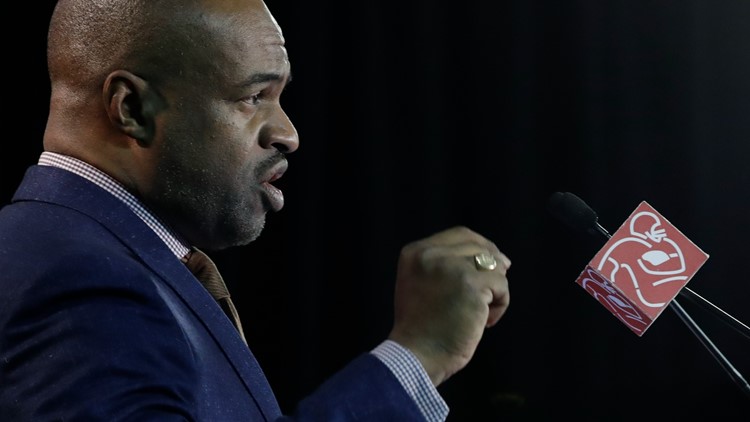

He’s not a star quarterback or powerful lineman. Nor is he a well-known coach or owner. DeMaurice “De” Smith is the Executive Director of the NFL Players Association (NFLPA) -- one of the oldest and most influential labor unions in sports.

And while the name “De Smith” may not be a household name outside of the NFL, there is no mistaking Smith among the wealthy -- mostly white -- owners of all 32 NFL franchises he is called upon to stand up to during negotiations.

“I've probably said things to NFL owners that would have gotten either one of my parents killed back in the day,” Smith told WUSA9's Eric Flack in a one-on-one interview at NFLPA headquarters in downtown D.C. “And I know for a fact, there are people in the league and NFL owners who probably won't be sending De any birthday presents during Super Bowl week. But that's the job.”

Smith has led the NFLPA for nearly 12 years, demanding justice for Colin Kaepernick and supporting players' right to kneel during the National Anthem. He continues to encourage his players to speak out amid nationwide calls for social justice and police reform.

“The years that we've been dealing with our players, taking strong stands on social justice, those have been the best years that I've had in this job,” Smith said.

Humble Beginnings

Smith was raised in Upper Marlboro, Maryland, by his parents, Arthur and Mildred Smith. Arthur Smith grew up in a sharecropper’s family, farming land for other people to make a living before joining the Marines.

“When looking at my life he didn’t want to go through what I had to go through,” Arthur Smith said of his son. “It seemed like to me, anything that he wanted, I don’t know how, but he just gets it.”

Mildred Smith was a twin whose father abandoned her and her sister at a young age. She quietly put herself through a segregated nursing school to get her license.

“I was so interested in him accomplishing things and not being afraid to speak up,” she said of her son. “Like I was afraid to speak up.”

DeMaurice “De” Smith impact on NFL, NFLPA

“He gave me the jacket off his back."

Smith was a leader from his early days at Riverdale Baptist High School in Upper Marlboro. His former football coach Jim Beckett said Smith was the captain of the high school football team and class/student body president during college.

Smith has remained close with his former football coach and has continued his involvement with the school, helping raise money for a new football stadium. The coach remembered running into Smith at a store in Bethesda, Maryland, after Smith had taken over as Executive Director of the NFLPA.

Beckett complimented the NFLPA jacket his former player was wearing.

“And he immediately took it off and goes 'here,'” Beckett recalled, motioning that Smith handed him the jacket right off his back.

“I said 'really, I was just playing with you,'" Beckett said, laughing. "'I don't really want your jacket. But if you want to give me your jacket, I'll take it.'"

“I never thought I would be in a place like this.”

After graduating from a small Christian college in Cedarville, Ohio, Smith appeared destined to use his voice as a Baptist preacher, as a number of his family members had before him. But after taking a year off and studying philosophy at the University of Maryland, Smith decided to enroll in law school at the University of Virginia.

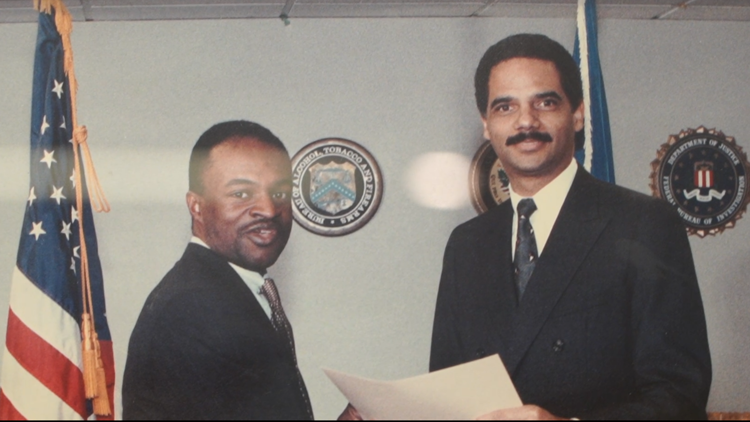

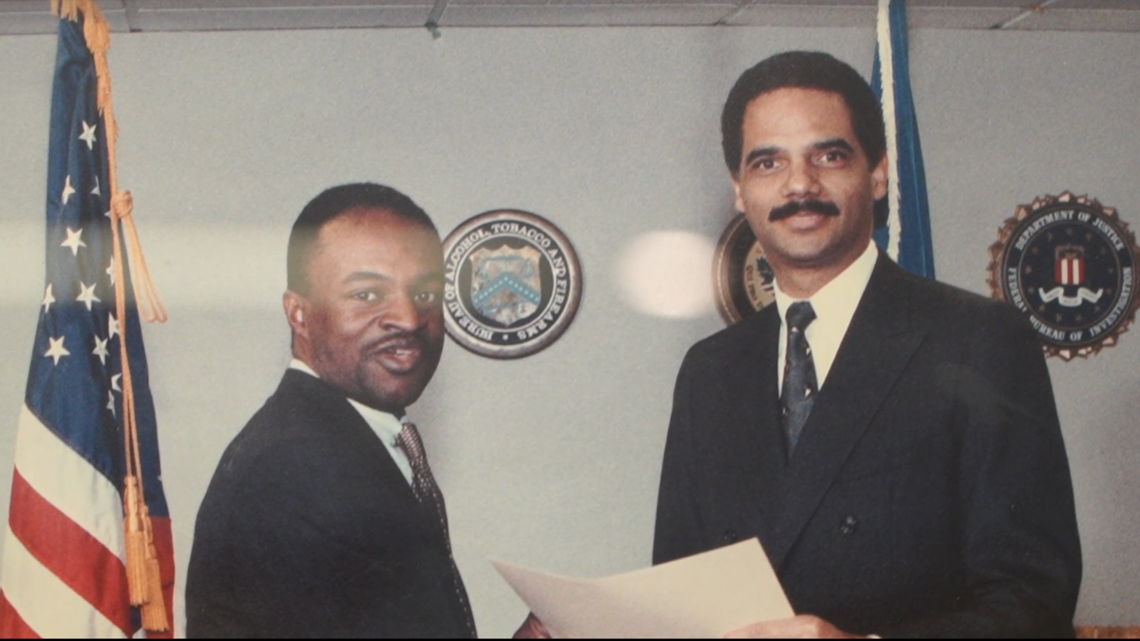

He started out in private practice for a white-collar law firm in downtown D.C. and spent nearly a decade working as a federal prosecutor alongside then U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia Eric Holder.

“At the time that I was the U.S. Attorney, people tend to forget [DC] was called the homicide capital of the country,” Holder said. “We had the highest per capita murder rate in the country. And so, people like De and the other people he served within the homicide section were essential parts in our fight to get the homicide rate under control.”

Smith and Holder remain friends to this day.

“While I was there it was exhausting, it was grueling and, in some respects, it was the best job I’ll ever have,” Smith said.

After returning to private practice, Smith thought he was headed for a reunion with Holder after his former boss was tabbed to be President Barack Obama’s attorney general.

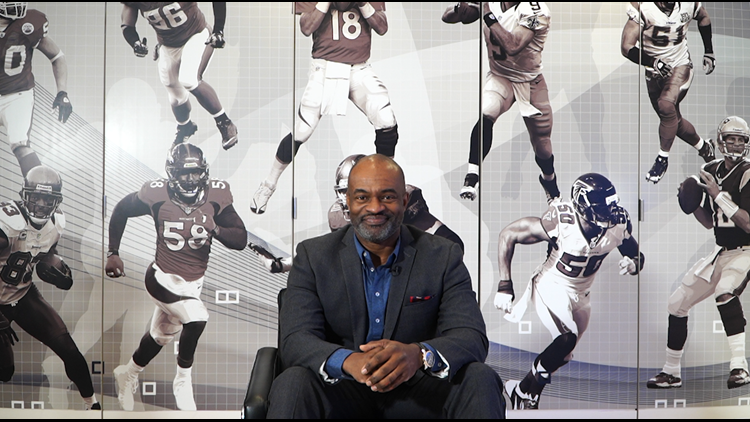

But while working on the Obama transition team in 2009, Smith got the call he was on a shortlist of candidates to be named the new Executive Director of the NFLPA. And Smith once again called an audible on his career.

“It's just sort of that point where the opportunity comes to you and you just sort of feel like it's time for a change,” Smith said. “I never thought I would be in a place like this.”

Smith followed in the footsteps of legendary NFLPA executive director Gene Upshaw, whose duct tape-covered game helmet, the same one he used for his entire 15-year career, still sits behind Smith’s desk.

Smith said it’s a reminder of the enduring struggle players face on and off the field.

“If there has to be a battle for what's right, we have to step up to that battle," he said.

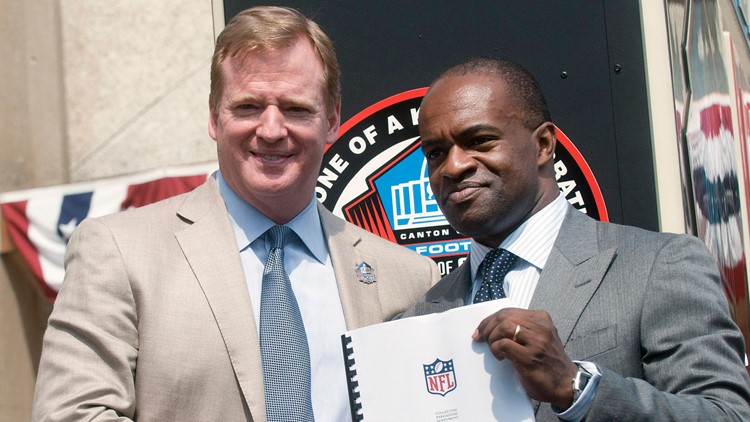

Smith led the players union through a four-month work stoppage in 2011 and helped negotiate two collective bargaining agreements between the NFLPA and the owners. His work helped win concessions on health and safety protections, pensions and salary guarantees.

DeMaurice “De” Smith impact on NFL, NFLPA

But it was the Colin Kaepernick story, and accusations NFL owners were blackballing him from the league for taking a knee during the national anthem, that thrust Smith into the national spotlight.

Now, amid continued social justice protests by many of the players he represents, Smith must once again guide NFL players on how best to use their influence when speaking out about race, inequality and police reform.

Smith said seeing tens of thousands of protesters marching through the streets of the District demanding change in the wake of the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, and then the violence at the US Capitol on Jan. 6, only further highlights the need for change.

“It's been hard to watch, hard to digest,” Smith said. “But these cycles of conversations about race, class, and power, those are things that have always existed in our country. And, and in the worst moments, you saw that explode on Capitol Hill.”

“Grow up in a house with a lawyer, you learn how to argue.”

In his home life, Smith doesn't shy away from bringing his knack for spirited conversations to the dinner table with his son Alex, a Division 1 lacrosse player at the University of Maryland, and his daughter Elizabeth, a small business owner in Bethesda.

"I mean, if you grow up in a house with a lawyer, you learn how to argue,” Elizabeth Smith said. “You learn how to present a defense and you know how to endure cross-examination.”

Alex Smith said any differences of opinion are usually settled by their mother Karen, who eventually leaves the dinner table rather than listen to his continued back and forth.

“When it comes down to it, he is a service worker for the players,” Alex Smith said. “And I think it gets kind of lost, because obviously, you see these young kids signing multimillion-dollar contracts, and you don't think of them too much as workers in a job rather than just performers or athletes. But when it boils down to it, they're putting their body on the line for entertainment for the rest of the country.”

“It's important for them to know how significant their choice is.”

Despite the time spent on family and his leadership role at the NFLPA, DeMaurice Smith has remained focused on the community where he grew up.

In 2018, The Georgetown Lombardi Cancer Center honored Smith with the Margaret L. Hodges Leadership Award for Smith’s multi-year support of the Lombardi Gala, the cancer center’s flagship fundraising event.

But it is Smith's continued work on behalf of more than 2,400 active NFL players that remains his driving force.

“Football is a great game, but there is nothing that our men or their families do that I think should remove them from the issues that are compelling in their community, and the issues that are compelling in our country,” Smith said.

He understands there will be criticism against NFL players that take part in on-field demonstrations supporting social justice, but sees those moments as teaching opportunities.

“Again, I know because I've heard it firsthand from not only some of our fans but at times in my extended family,” Smith said. “Why can't we just have football without politics? Well, what happens in this country that isn't in some way, shape, or form touched by what's happening in our communities? I think it's important for them to know just how significant their choice is, but also to realize, and hopefully draw strength from the fact that you weren't the first. And you probably sure as heck won't be the last. But do it because it's the right thing to do.”