MANASSAS, Va. — Wilmer (Billy) Fields, Jr., pulls his jet-black Ford Tundra into the driveway, past the For Sale sign in the front yard of the two-story home with the fresh white paint. His father died in 2004.

"Mom passed just four months ago at 90," Billy said. "It was time...but it was still hard."

Deciding to sell the house wasn't easy. He grew up in this house, the only one his parents knew, the home his father bought with money earned playing pro baseball.

But a man can only hold on to so many material possessions before they go from sentimental to just ... stuff.

And Wilmer Fields, Sr., Billy's father, had a lot of "stuff."

- A duplicate of the Homestead Grays scratchy wool jersey he wore in the 1948 Negro League World Series.

- A candy dish full of valuable, signed baseballs -- yet to be given away or sold.

- Yellowing game programs featuring the Kansas City Monarchs and the Baltimore Black Sox, with names of men who have been gone for decades

- Grainy black-and-white team photos taken at Griffith Stadium some eight decades ago -- autographed by Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Luke Easter and other Negro Leagues stars of the day.

And the closer, a flat-out baseball artifact, replete with a written letter in blue ballpoint from Wilmer Sr.

"In '48, I forgot my jacket on a day I pitched against the Birmingham Black Barons," the artifact reads. "I borrowed [Willie} Mays' jacket. At one time the jacket had Mays' name taped to it. After the game I forgot to give it back to him. The jacket has remained in the attic for years..."

After some prodding, Billy brought out the all-black, satiny warm-up that once belonged to the Say Hey Kid. If one can creep any closer to a religious experience in baseball, it would have to be at a ballpark or an Iowa cornfield.

"This was just some of Dad's things -- he has more," Billy said, pulling the framed jacket from the bedroom, pulling out a piece of history we've unintentionally forgotten this week.

Seventy-one years ago, the Washington Homestead Grays won their own National League pennant.

They held off the Baltimore Elites to advance to the last Negro League World Series, where they beat the Black Barons to claim their 10th Negro League title in 12 years. This was before the Major League money became too lucrative for African-American players to thumb their nose at, when baseball began fully integrating -- 15 years after the Washington Senators last played in a World Series.

From the Washington Post to MLB.com, the sport's official website, the year is always reported the same: 1933. And if we're talking strictly the Major Leagues, the answer is correct. These resilient, get-off-the-mat Washington Nationals, who are playing in their first World Series, are the first Major League ballclub in D.C. since the '33 Senators to win the pennant.

But if we're talking pro baseball, we're talking Wilmer Fields and the Grays. It's more than semantics or a technicality; it's important -- especially given the segregated world they not only played in but very much lived in.

Wilmer was bi-racial, a fact that actually helped his black teammates in towns that wouldn't serve people of color in the 1940s, even if they were famous people of color, whom tens of thousands cheered for at games.

"He had blue eyes and he was very light-skinned," Billy said. "The story was, he'd go into places where blacks weren't allowed during that time period and buy food for the bus while they were traveling between games. But there was one time when he went into a restaurant to order food and one of the ballplayers wanted him to place more orders for food. So when the ballplayer walked in, the owner of the restaurant looked up and saw the bus that said Grays. And [the owner] told them, 'We don't serve blacks.' "

Gas was 16 cents a gallon. A new home cost less than $8,000. Harry Truman was in the White House. 1948 -- the year that should rightly be championed as the last time this town won a pennant. The Nationals haven't forgotten; they erected a statue of Josh Gibson in the summer of 2009 at Nationals Park along with statues of Frank Howard, their own Sultan of Swat from 1965 to 1971, and Walter "Big Train" Johnson, who pitched the Senators to their only World Series victory in 1924.

I became aware of this story in 2012 when the Nationals made their first postseason. I spoke to Billy's mother and Wilmer's wife, Audrey, then 82, about Major League Baseball and media organizations needing to acknowledge the fact. Like her son, she didn't worry herself about such things. But Audrey Fields added, “Well, that would be nice if they did [acknowledge the Grays]. Because a lot of family members remember those players and that team. Wilmer very much liked playing for them.”

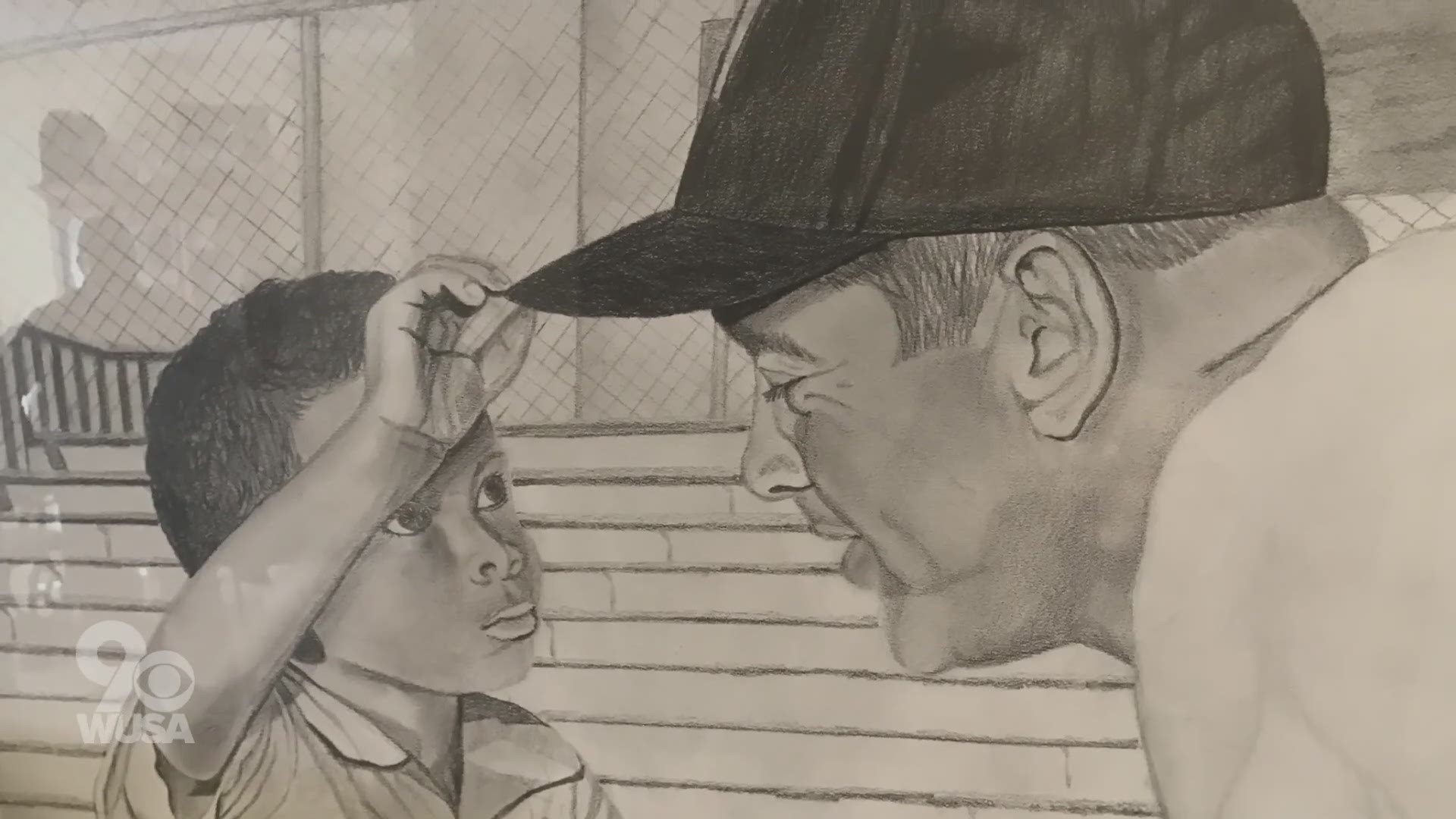

Wilmer had a vicious, tailing fastball and also played third base for the Grays. Billy knew none of this as a child until he began going to reunions with his father and found out from conversations with other Negro League players: "Dad wasn't just good; I kept hearing time and again how great he was," he said.

"I was at one reunion game in Canada and Dad was over 50 at the time," Billy added. "I saw him hit a ball, like, 385 [feet]. And it got out in seconds. Then I was in Puerto Rico where he pitched against the Puerto Rican all-stars in Ponce, and I was warming him up. And he was throwing this knuckleball and it was dancin' all over the place."

"I knew when he was throwing batting practice to us, when he coached us, that he could strike any of us out when he wanted," Billy said. "So, yeah, I knew there was something there."

The Grays played before full houses at Griffith Stadium, where Howard University Hospital now sits. The Senators were the main tenant, and no one was made more acutely aware of that than the Grays; they had to play all their playoff games to get to the '48 Series in Baltimore. Why? Because their home ballpark was already rented.

Griffith Stadium was 405 feet down the line. It had a huge right-field wall (ala Fenway Park's Green Monster in Boston) and it measured 457 feet to dead center. Josh Gibson, the greatest home run hitter of his era -- white or black — hit 11 balls over the wall to left and center for the Grays in 1943. That same season, the entire American League, encompassing roughly 300 players, hit just 10 home runs over the left and center field walls of Griffith Stadium.

The stadium held 27,000 but newspaper accounts at the time, according to Brad Snyder's 2003 book "Beyond the Shadow of the Senators," said almost 32,000 crammed into Griffith in 1942, the day Gibson, Buck Leonard, Luke Easter, Satchel Paige, and Cool Papa Bell were all on the same field.

"Dad and I would always sit around and talk about, 'What would Josh [Gibson] hit in the majors?' Billy said. "When we would talk about Satchel [Paige], I would ask him to compare him to someone in the majors. He would always say Nolan Ryan because of his velocity on his fastball."

The Senators did not integrate until 1954, a full seven years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. In Washington, the price of passing on some of the best black players of that era was steep. Robinson, Roy Campanella, Paige and Larry Doby were plucked by the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Cleveland Indians between 1947 and 1954. The Senators missed out on an entire generation of African American superstars that would come to dominate the major leagues -- among them Mays, Henry Aaron and Frank Robinson, baseball's first African American manager who became the Nationals' first manager in 2005.

You could probably make a decent argument that any of those players would have enraptured baseball crowds in Washington, where some of the sorriest Senators' teams (.378 winning percentage) engendered the saying, "Washington, first in war, first in peace and last in the American League." Would the Senators have left for Minnesota in 1971 if they had built up more of a reservoir of goodwill among local baseball fans, especially black baseball fans? Hard to say.

Either way, Billy, 59, said his father never harbored resentment, that he was happy to be important to people after he retired:

"He was never bitter about it," he said. "I think when the Negro Leagues started getting the recognition, I think that was a big thing for him."

Wilmer Sr. became president of the Negro League Association in his later years. Part of his legacy involves procuring health benefits and pensions for surviving players at the time.

What is not generally known is that he had five offers from other Major League teams. He turned them all down to raise three children and be a husband in this home.

"Dad, through the record books and everything, was a great baseball player," Wilmer said. "But I think he was a greater father."

Wilmer coached his kids, fished with them, encouraged them in all their pursuits. And when the day came when Billy had to decide between baseball and basketball in his senior year in high school, he accepted a basketball scholarship to Providence with his father's blessing.

"Toward the end of his life, we had this one day out on the [Chesapeake} Bay that was just totally incredible," Billy, Jr. said. "I think we caught 30 big stripers (striped bass). He talked about that day ever since it happened until he passed."

Somewhere near that body of water, in an area called Point-No Point near Solomons Island, Maryland, Wilmer Fields' Jr. took the ashes of his father -- the old Homestead Grays pitcher -- and, learning over his boat, spread them in the current.

"I think it should be acknowledged," he said of the Grays being Washington's last World Series team. "It's everybody's opinion and I could go one way or the other. But, yeah, I think it should be acknowledged."

This story is part of a new show called The Q&A. If you’ve got questions, we want to answer them. Each night at 7pm and at wusa9.com/theqanda, we’ll tackle everything that you want to know. Just use #TheQandA on social media, email us at TheQandA@wusa9.com or make a comment/mention on any of our Facebook/Twitter/Instagram pages. The author is @MikeWiseGuy on Twitter, MikeWiseGuy44 on Facebook and MikeWise319 on Instagram.