SILVER SPRING, Md. — She thought her uncle vanished somewhere along a faraway and forgotten horizon, an expanse of the South Pacific few have ever seen.

Now, a lagoon with untouched wreckage of war is part of her family’s story, after the Pentagon identified the remains of a World War II pilot lost in a cataclysmic crash.

Janice Hechler, 77, placed four medals on her dining room table, all belonging to an uncle she never knew.

A golden eagle clutches two bolts of lightning, the centerpiece of the Air Medal, awarded for heroic or meritorious achievement in flight.

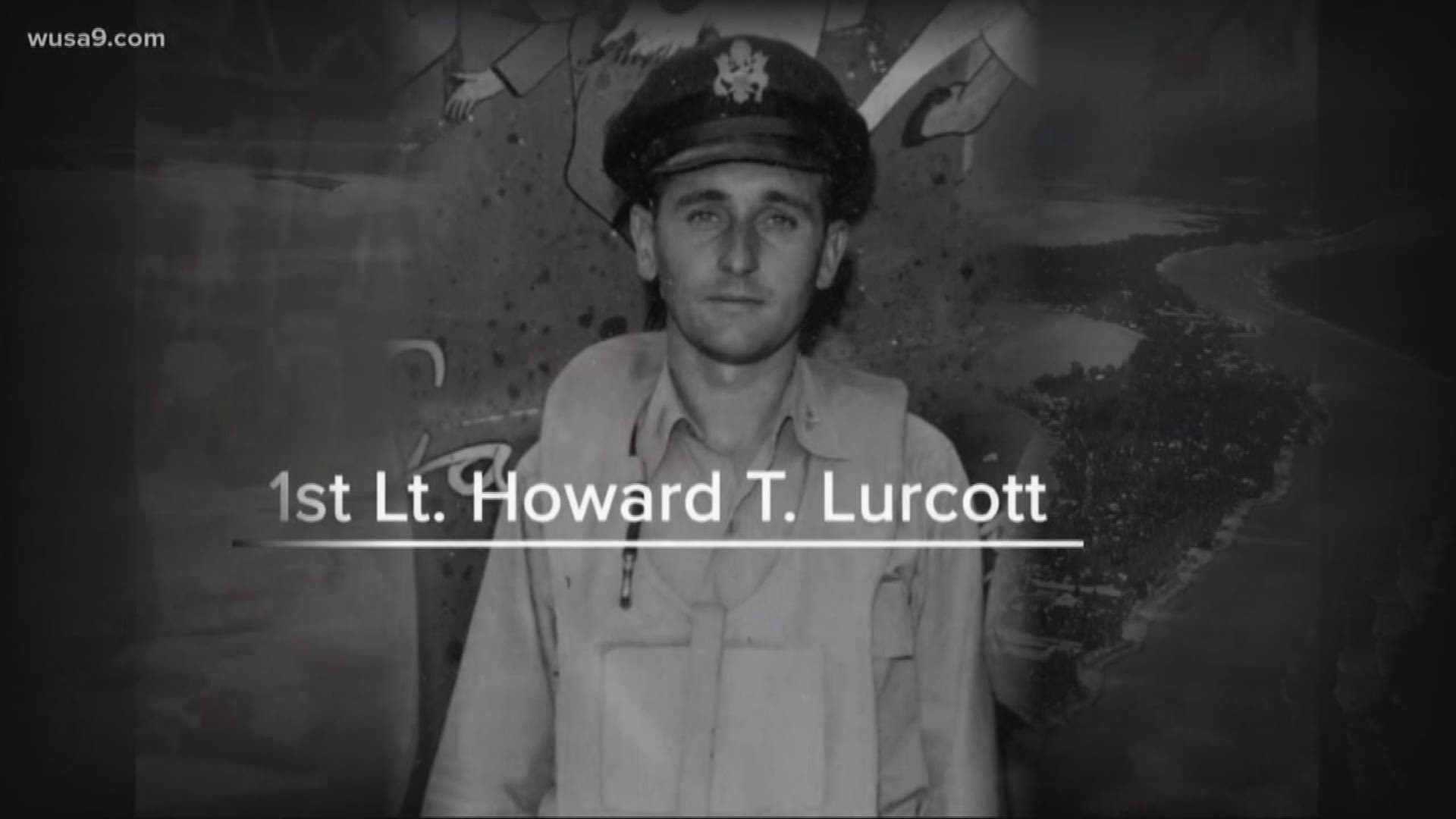

The gleaming medallion is the highest honor given posthumously to 1st Lt. Howard T. Lurcott, a U.S. Army Air Force pilot who fought 7,000 miles from Silver Spring.

He was 26 years old – an unassuming hero who never returned home.

Lurcott died when his chrome B-24 bomber crashed off the remote Tarawa atoll. Hechler was only three.

Family members accepted that he was gone, his fate they thought forever sealed as "missing in action."

But two generations later, anthropologists and military veterans working for History Flight, a non-profit dedicated to finding remains of MIA service members, found Lurcott’s nearly complete skeleton.

He was discovered in a lost grave on Tarawa, where more than 400 Americans are still buried in unmarked plots.

History Flight uncovered Lurcott’s remains in 2017, with the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory definitively linking the skeleton to Lurcott in January 2019.

Hechler received the confirmation phone call less than two weeks ago.

“I felt like the ceiling had come down on me, it was just, it was overwhelming,” Hechler said in an interview.

“I didn't know that there was anything left of him. The pictures of him... I had never seen him, I didn't even know what he looked like.”

WUSA9 visited Lurcott’s Tarawa crash site in June 2017, during the start of a two-year investigation into American repatriation efforts on Tarawa.

In an interview on the island, anthropologist Hillary Parsons said History Flight found coffins within its most recent excavation area.

DNA evidence now shows one of the coffins belonged to Lurcott.

Anthropologists initially realized the 2017 discovery indicated they uncovered service members who were buried after the November 1943 primary attack on Tarawa.

Coffins took time to assemble, and could only be made for the small number of people who died in the relative calm after the main battle.

The timing of the coffin burial matches with the date of Lurcott's crash, January 21, 1944.

The night on Tarawa was nothing short of catastrophic. Seventeen minutes before Lurcott’s flight, an earlier B-24 bomber based on Tarawa also crashed into the lagoon.

Archival documents show engine problems were reported minutes into Lurcott’s mission, with two explosions later heard at 12:38 a.m.

Defense officials reported water most likely mixed with gasoline in Lurcott’s engine, dooming the bomber.

Wreckage of the crashes can still be seen to this day, with locals allowed to walk up to wings and engine parts at low tide.

The bomber flew at least eight World War II combat missions – Lurcott and his nine crew members were on their way to confront the Japanese above Roi Island at Kwajalein Atoll.

It remains unclear how Americans found Lurcott's body in 1944, but defense personnel placed his remains within a Tarawa cemetery for the war dead.

As for why his homecoming was delayed 75 years – his grave was lost largely because of efforts to beautify the area known as Cemetery 33.

Records show white wooden crosses were often moved far from actual graves – as American construction crews in the 1940s attempted to create a more orderly and symmetrical burial ground.

There was no body under the cross marked "Lurcott," and efforts to find his remains ended by 1950.

After more than a decade of research, History Flight excavated Lurcott's coffin and nearly complete skeleton. The non-profit continues to work on Tarawa, excavating the largest number of MIA Americans spread throughout the world.

The Army flew Lurcott’s remains from a laboratory in Honolulu to Arlington National Cemetery this week. Lurcott received a full burial with military honors Wednesday morning - a promise of no man left behind, now fulfilled.

“I think it's terrific, the way they've handled this and have brought him back,” Hechler said. “I really do. I'm overwhelmed by it.”