WASHINGTON — On a frigid morning in February, Jason Fuentes found himself in a hole.

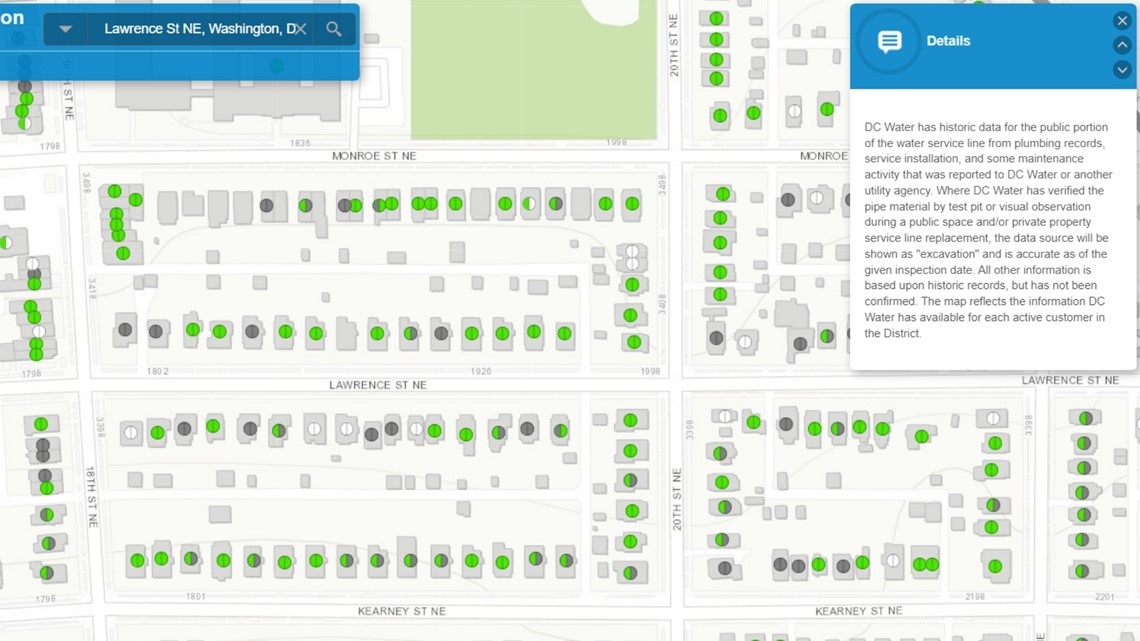

It was just after 10 a.m., and his New York Giants sweatshirt was already crusted in a layer of dirt and mud. That hole sat in the middle of a front lawn on Lawrence Street, N.E. in the district. By his feet, a tool called a "bullet," akin to a jackhammer, was roaring as it paved a tunnel from this hole to another one on the sidewalk.

All of this was being done to make room for a brand new copper pipe, which will replace a potentially dangerous lead one.

Later, they'll cut through the asphalt to the concrete and connect the new pipe to the water main.

"Parálo! Parálo!," he yelled, Spanish for 'stop it.'

The noise of the bullet came to a stop. Fuentes was one of about a dozen crew members working to replace this lead pipe. It's a laborious process that will take half a day to complete.

"This is what I do every day," he said while shoveling. "I’ve been doing it for 12 years."

This process has been replicated thousands of times across the country. Teams donning yellow safety vests have been working for decades to counter an epidemic of lead pipes, sometimes in the 'service lines,' which connect the water main to houses. Lead can cause medical problems if it gets in the water.

The EPA estimates up to 10 million lead pipes still remain, buried underground in communities big and small. But before any work can be done, utilities need to know where the lead pipes are.

Does D.C., Maryland and Virginia know where their lead pipes are?

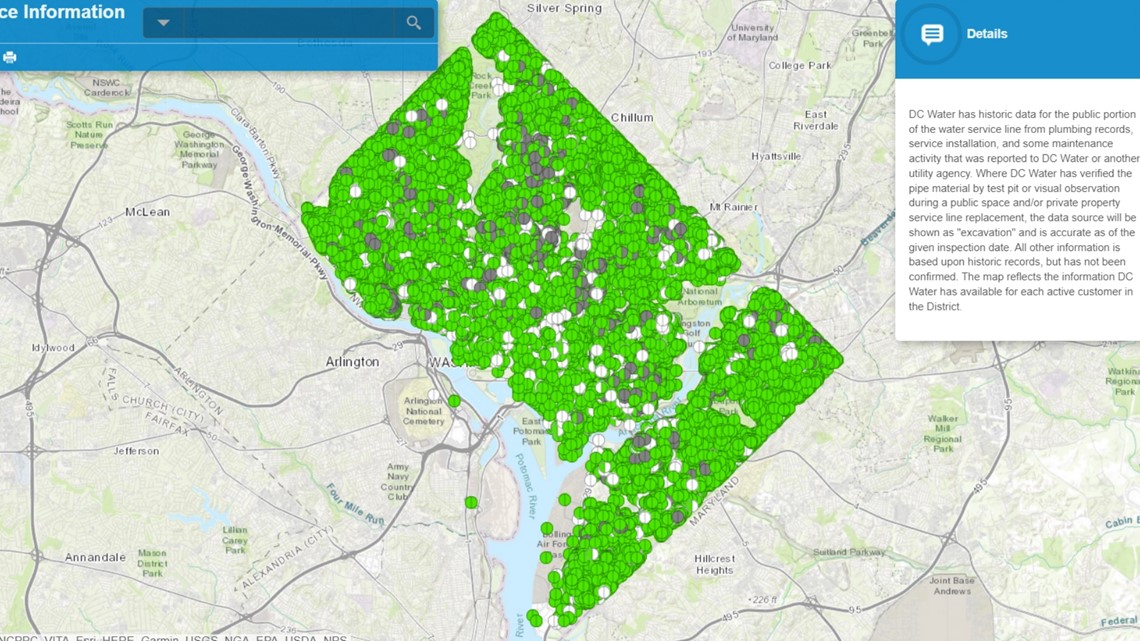

Our Verify researchers brought this question to the people in charge of water quality in all three jurisdictions. We discovered D.C. has the best handle on the quantity and location of lead pipes.

"We have a lot of historic documentation that has a good indication if there's [a] lead pipe," Schmelling, a 17-year D.C. Water veteran, said. "We also have excavation records—but essentially, we have to come to the block and we dig down to the service line in the yard space, and then we can see the pipe. And that's how we determine whether they have [a] lead pipe."

D.C. Water has a block-by-block map showing where they think lead pipes are. While the map is robust, it is not complete: there are several addresses marked with a white dot, representing "no information."

Click here to access DC Water's lead pipe map.

According to Schmelling, there are about 30,000 lead pipes in the District, 10,000 of which are on the public side and 20,000 which are on the private side. She said the cost to replace just one ranges between $10,000 and $15,000.

You can see how the cost easily adds up: paying for a crew, excavating the street, sidewalk and yard, then refilling the concrete and asphalt ripped up to reach the water main.

"In addition to that, there's all the management of the project and making sure we meet all of DDOT's (Department of Transportation) permit requirements and all of our signage, and making sure that everybody is safe on the job site, and pedestrians and cars are safe," Schmelling said.

D.C. Water is well aware of the problems lead pipes can cause.

In the early 2000s, D.C. Water changed the chemicals used to treat water, causing lead pipes in the city to corrode.

"Nobody realized at that time that changing our disinfectant would actually cause the lead to leach into the water," Schmelling said.

The more water utilities, the harder it is to create an accurate inventory

Meanwhile, finding statewide numbers in Virginia and Maryland is not as easy.

"The reason we don't know how many lead service lines there are is because it wasn't tracked," Dwayne Roadcap, the Director of the Office of Drinking Water at Virginia Department of Health, said.

Unlike D.C. where there is one major water supplier, Virginia has 2,830 water utilities, according to Roadcap. He said utilities are not required to track lead pipes or report their location to the state.

“I think some of the utilities have better information than others," Virginia's top tap water official said.

Roadcap said testing remains important, since lead is out there.

"Even though we know that we have lead service lines, we also know that the drinking water is safe, because we're doing a good job of monitoring the water quality, and making sure that the lead is not leaching from the pipe," he said.

You might be wondering, 'doesn't the federal government require utilities to track lead pipes?'

Not really.

Under the Safe Drinking Water Act, the law that governs tap quality, there are two main parts that apply to lead.

The first part involves the use of lead pipes.

In 1986, the SFWA banned water systems from installing lead pipes and solder containing lead, or using it for repairs.

The second part pertains to testing for lead: it's called The Lead and Copper Rule.

In 1991, the EPA created a limit—what they call an "action level"—on how much lead could be in drinking water before corrective action is needed. That limit is 15 parts per billion.

The Lead and Copper Rule requires utilities to sample tap water in their distribution area, and if more than 10% of the samples collected exceed 15 parts per billion, utilities do certain things like corrosion control, reaching out to customers, and if the levels are high enough, lead service line replacements.

Those samples must be collected from sources with known or suspected lead pipes.

"Systems had to do materials inventory to identify those sampling locations. Those weren't comprehensive," a senior EPA official said. "There's also the situation where if a system exceeded the action level previously, they had to have an inventory because they were triggered into a lead service line replacement requirement...and they needed to replace a certain percentage."

Up until Dec. 2021, there was no federal requirement for states to compile an inventory of lead service lines owned by utility companies. More on that later.

Lead is more common in houses built in the early 1900s

While Roadcap said there is no statewide total, he said older places like Richmond, Newport News and Alexandria are known spots to find lead.

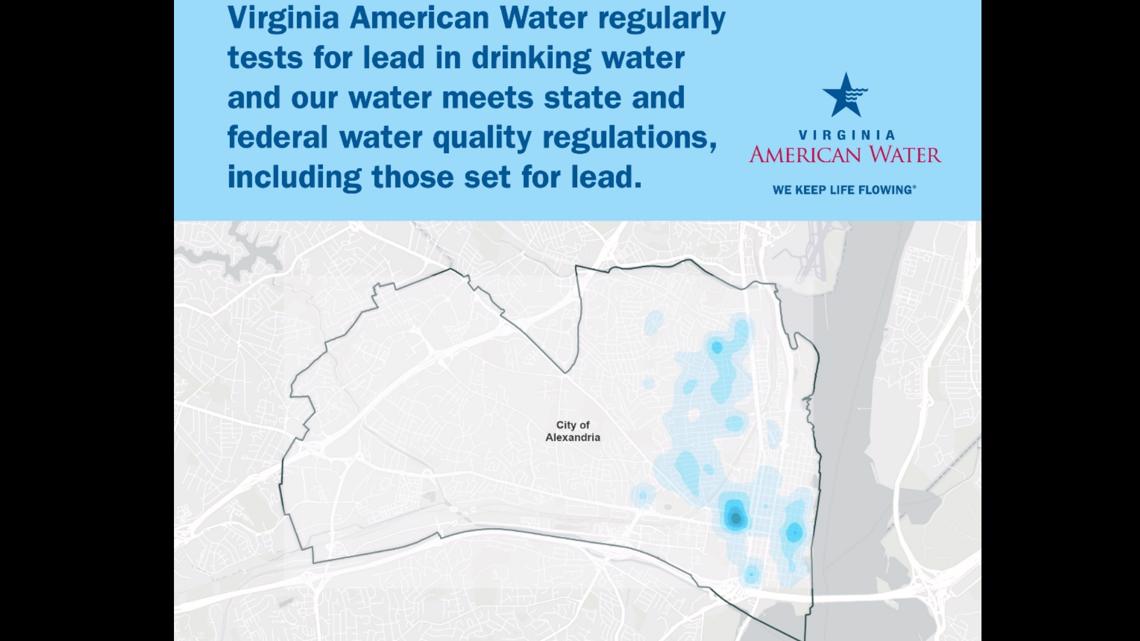

Our Verify researchers contacted Virginia American Water Company (VAWC), the sole water distributor in Alexandria.

In 2018, there were 2,641 utility-owned service lines classified as "potentially lead, unknown or presumed lead" in the city, according to a VAWC spokesperson.

Since then, she said the utility has reduced lead pipes by 25 percent, and that, statewide, about three percent of VAWC's service lines contain lead.

The company provided a heat map of where they believe lead pipes may be.

What about Maryland?

Similar to Virginia, Maryland also doesn't keep a record of lead pipes used for drinking water.

"We don't know how many lead pipes there are. We don't know how many lead-infused fixtures there are. It's a priority for us," Ben Grumbles, Secretary of the Environment, said.

Maryland has about 470 community water systems, and while Grumbles said they did do an inventory of lead pipes five years ago, they got sporadic answers.

They’re also doing regular testing at schools.

As of Feb. 7, the state had received 70,640 water samples taken at schools. It found that lead levels exceeded 20 parts per billion, which is over the EPA limit, in more than two percent of the drinking water outlets.

“This is a manageable problem that we can help fix," Grumbles said. "So it was not— it's not an overwhelming crisis.”

Lead pipe inventories are now required under a December 2021 amendment to the Safe Drinking Water Act

So as of right now, D.C., Maryland and Virginia don’t know where all the lead pipes are.

That’s because the EPA’s focus has been more on testing for lead rather than replacing pipes. But that will soon change.

Under a new amendment to the Safe Drinking Water Act, all states must submit a full inventory to the EPA by Oct. 2024, which means states and utilities must work on compiling all that data now.