WASHINGTON — Between an upcoming inauguration and a violent breach at the Capitol, topped with a tumultuous election cycle and dozens of protests, even more attention has been brought to the District of Columbia lately.

To help break down the powers of D.C. and how they came to be, as well as how statehood might impact them, here's a cheatsheet:

Is DC considered a city, a state, or neither?

By definition, D.C. stands for the District of Columbia, meaning it's not quite a state but you guessed it, a district. It's also the capital city of the United States.

So how did it end up as the District? That answer is tricky, requiring a look back into the city's diverse history.

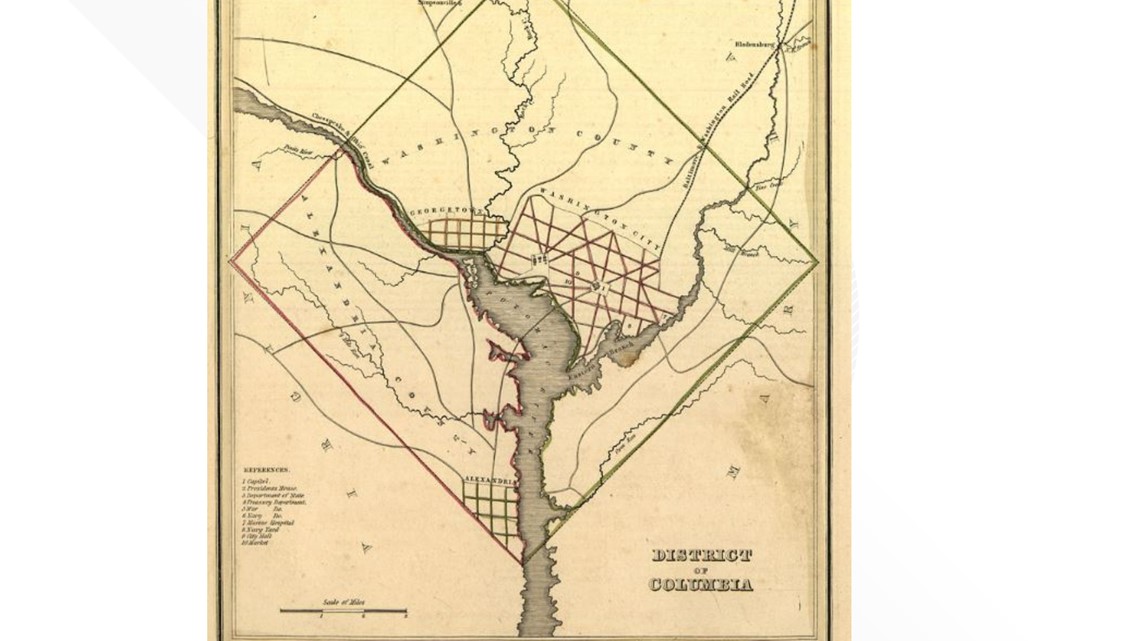

Back in 1790, Congress first established the federal district by taking land belonging to Maryland and Virginia to re-apportion for what would become the nation's capital.

Originally, D.C. consisted of five different areas:

- Washington County, the more eastern and northern parts of D.C. that are closer to Maryland

- City of Washington, the main core of the city with those federal buildings

- Alexandria County, the south and west part of D.C. closer to Virginia

- City of Alexandria, pretty much the same territory we know today

- Georgetown, area similar to the neighborhood today

The Organic Act of 1801 officially gave control of D.C. to Congress and organized the District into two counties: Washington County, north and east of the Potomac, and Alexandria County to the south and west; the existing cities of Alexandria and Georgetown were left alone.

Back in the 1830s, residents in Alexandria County -- then a major market in the slave trade-- grew frustrated with economic concerns that Congress would block slavery in the District. In 1846, they petitioned Congress who then voted to "retrocede" the Alexandria County and city of Alexandria back to the state of Virginia.

What was left was Washington County, Georgetown and the City of Washington, who combined together to form one area: the roughly 177-square kilometer land of Washington, D.C we know today.

Who governs D.C.?

D.C. has its own set of legal codes, like states, but unlike states, doesn't have a governor presiding over it. Instead, the District has a mayor, a title currently held by Muriel Bowser.

Like a state, there are three branches, all with different titles. Instead of governor, a mayor. Instead of a state congress, a council.

D.C. also operates a District-run police force and a public school system, with its own unique laws on liquor control, unemployment compensation and even food and drug inspection. It has its own legislature, the Council of DC, and an Attorney General, Karl Racine. This is why you might be able to buy specific alcohol or marijuana within District limits but not within neighboring states like Maryland or Virginia.

And as mentioned earlier, D.C. does have one member in Congress -- Eleanor Holmes Norton, who isn't able to actually vote. She can sit on committees and influence decisions but doesn't hold the actual power to place a vote like other states.

D.C. also has two 'shadow' senators, currently held by Paul Strauss and Mike Brown. Neither Strauss nor Brown are officially sworn or seated by the U.S. Senate, meaning they get no voting power, but can advocate for issues on behalf of their D.C. constituents.

Why is statehood all that important if D.C. already has so much of its own authority?

While D.C. does have autonomy in certain aspects like its own police force or its Council, it's still overseen by Congress.

There are four Congressional subcommittees, both chambers of Congress (House and Senate), four regular committees and the president who all can oversee the ins and outs of D.C.

It's Congress who can modify and review D.C.'s budget, and also overrule any law it doesn't like. Whoever is president appoints D.C. local judges, who then help run D.C.'s court system and even its jail -- some of the core benefits that states enjoy that aren't available to D.C. officials.

"When the federal government shuts down because Congress can’t agree on a spending bill, the District is required to shut down as well," reads a budget explainer from DCVote."During those periods, basic local functions like education, trash collection, and permitting cannot be carried out."

So D.C. doesn't truly enjoy the same benefits a state would. Federal decisions that are often heard as "leaving it to the states" for enforcement don't apply the same way here in D.C.

What would change under statehood?

D.C. has roughly 700,000 residents who currently pay federal taxes and who do not have equal voting representation, so statehood would help protect those residents.

D.C. becoming the 51st state would also mean the District would have two voting senators. D.C. also has the option to undergo retrocession, which would put a majority of the District into a new county in Maryland, where they would be represented by that state's leaders.

June 2020 marked the first time that either house of Congress has passed legislation that would allow D.C. to have full statehood and congressional representation.

The bill would shrink the federal government territory to a two-mile radius (dubbed the "National Capital Service Area" ) that would include the White House, Capitol, Supreme Court and other federal lawmaking buildings that would still stay under congressional control.

It would still need to be passed by the Senate —where a filibuster and potential kill may occur — before actually allowing D.C. to become a state.

Just this month, Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton, who authored the bill, re-introduced the statehood legislation to the new members of Congress.

"The Constitution does not establish any prerequisites for new states, but Congress has generally considered three factors in admission decisions: resources and population, support for statehood and commitment to democracy," Norton stated in her January update of the bill's cosponsors.

"D.C. pays more federal taxes per capita than any state and pays more federal taxes than 22 states," she continued, advocating that D.C.’s population of 712,000 is larger than those of two states and that the new state would be one of seven states with a population under one million.

Hasn't D.C. tried to be a state before?

The short answer: Yes.

Critics of D.C. statehood argue that the framers of the Constitution never wanted the nation’s capital to be its own state. They say creating a new state would call for a constitutional amendment and the new state -- with a proposed name of Washington, Douglass Commonwealth -- would have a disproportionate amount of influence over what the federal government can and can't do.

House bills H.R. 810 & H.R. 381 proposed the idea of D.C. retroceding back into Maryland for voting rights purposes back in 2001 and 2003 and failed. And in 2004, the District of Columbia Voting Rights Restoration Act proposed considering D.C. residents as Maryland residents strictly for congressional representation purposes. It never came out of committee.

Republican lawmakers have pushed back on the fight for D.C. statehood with legislation as recent as October 2020, proposing bills that limit the number of senators a new state could have or push heavily towards Maryland retrocession.

Retrocession means D.C. residents would still get Congressional representation by technically becoming Marylanders for voting purposes, but it would avoid adding additional seats to the House and Senate.

Regardless, D.C. statehood still needs to pass the Senate before actually being rolled out. And with a newly adjusted Congress, you might see that happen sooner rather than later.