ABERDEEN, Md. — Since the beginning of the pandemic, scientists have been researching COVID-19 to better understand symptoms, detection methods and containment/mitigation strategies.

But many people may not know, science has been lent a helping hand (or should we say paw?) from some four-legged aids.

Last fall, a team of researchers at the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command Chemical Biological Center (DEVCOM) partnered with the University of Pennsylvania and various canine training facilities to determine if dogs can be trained to detect the odor of COVID-19.

The Verify team looked into the science of COVID-detecting dogs.

THE QUESTION:

Can specially trained scent detection dogs sniff out COVID-19 positive samples?

THE SOURCES:

Dr. Patricia Buckley: Supervisory Biologist and Chief of the Biochemistry Branch at the DEVCOM Chemical Biological Center

Dr. Michelle Maughan: Contract researcher for the DEVCOM Chemical Biological Center.

The American Kennel Club

THE ANSWER:

Yes, dogs can sniff out COVID-19 with impressive accuracy, according to new studies.

WHAT WE FOUND:

The Verify team met up with several experts in a large, steel testing facility inside a secure building at the DEVCOM Chemical Biological Center on Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland.

"This is a very highly specialized building at DEVCOM CBC and it's one of the few buildings that is approved for explosives, chemical and biological threats," Dr. Michelle Maughan said. "So, it's highly sophisticated. And it's allowed us to do all sorts of really interesting work. And it's a great place to train dogs."

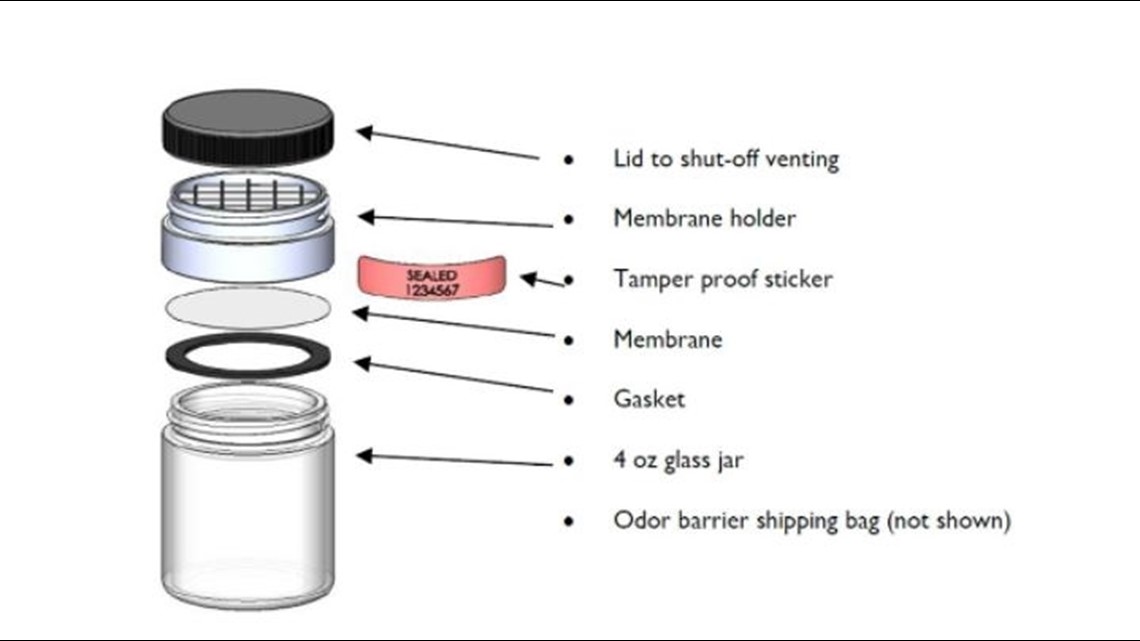

Maughan said the dogs are their number one priority and layers of security have been built in to protect and keep them safe. She explained that any threat being tested is contained in a specialized device inside what's called a TADD, the Training Aid and Delivery Device.

A stainless steel can protects the TADD, which has a specialized gas permeable membrane so whatever is inside cannot get out.

"It can be a powder, liquid, whatever's in here is not getting out, but the odor of it can," Maughan said. "Dogs can still smell, whether it's COVID, explosives, or anything else, they can smell it, but they can't get exposed to it."

Dr. Maughan recently began training Fenton, an energetic 9-month-old puppy that is highly motivated to work. She demonstrated how dogs like Fenton are trained to identify dangerous odors and explained how trainers use a scent wheel and place different odors in the TADD.

She loaded the chemical 1-Bromooctane into one of the TADDs then gave Fenton a "search" command. Fenton sniffed the TADDs, alerted to the correct one and was rewarded with a treat.

"I can recognize that his behavior is different, and when he gets a little bit older, we'll fine-tune that," Maughan said. "We'll make that a little bit sharper so that at the end of his alert for us is in a sit or a down."

Over the next year, Fenton will be trained and could become a bomb-sniffing dog, be trained to identify drugs or he could train to detect the smell of COVID-19.

Dr. Maughan said for dogs like Fenton, it's a game with a reward for each hit. Then it's the human's job to translate that into an operational, diagnostic or detection capability for the real world.

Dog noses have a dazzling sense of smell. In fact, according to the American Kennel Club some breeds of dogs have more than a hundred million scent receptors in the noses making them at least 100,000 times more sensitive than our noses.

In the fall of 2020, Dr. Maughan worked with a team of scientists from the University of Pennsylvania's Penn Vet, doctors and various canine handlers and researched how canines could aid in the fight against COVID-19.

Dr. Patricia Buckley, a supervisory biologist and chief of the Center's Biochemistry Branch led the team.

"Phenomenally successful” was how Dr. Buckley described the overall success of the study. The study she supervised, funded by the Defense Department's Domestic Preparedness Support Initiative, was a proof-of-concept one to see if there was enough odor in COVID that was detectable by dogs.

"Dogs have shown in the past that they could detect a lot of different diseases and that the changes in smell is really what allows them to alert on different diseases," Buckley said.

Dr. Buckley said the dogs were trained to discriminate between the odors of COVID-positive and COVID- negative people based on the volatile organic compounds left on the t-shirts. She noted participants in the "t-shirt" study had to send a COVID-19 test to verify their positive or negative status.

In phase one, dogs were given samples of urine and saliva from COVID patients and detected the illness at a rate of 68%; they correctly identified negative samples at a rate of 99%.

They then moved to phase two giving the dogs t-shirts worn by COVID patients. They were able to detect the virus on t-shirt samples at a rate of 84%, and were able to identify the t-shirts worn by COVID-negative patients 91.9% of the time.

"Dogs can smell a whole array of things that humans can't," Buckley said. "And so they are able to pick up on different odors. And really the difference of these dogs is that they're trained to alert on those differences.”

The study also showed the K9s could detect COVID much earlier than participants were showing any external symptoms like fever, chills or coughing.

"They are definitely able to alert on much lower amounts of the virus," Buckley said. "And so we have found in our studies that some of the negative samples that we received the dogs were alerting on, and then they were later testing positive."

Dr. Buckley said the study still needs to be peer reviewed, but it tracks with what experts currently understand about just how good a dog’s sense of smell really is.

“It's exciting to be able to work on things that actually can people can use out in the field," she said. "A lot of the research you do stays in the lab -- it’s small and contained, but this is something that can have large impacts across the world."