RICHMOND, Va. — Each election year, Virginia conducts a meticulous audit of its election system to ensure each voter the marks on their ballot are accurately recorded by voting machines.

It’s called a “risk-limiting audit" – the gold standard of election integrity checks nation-wide.

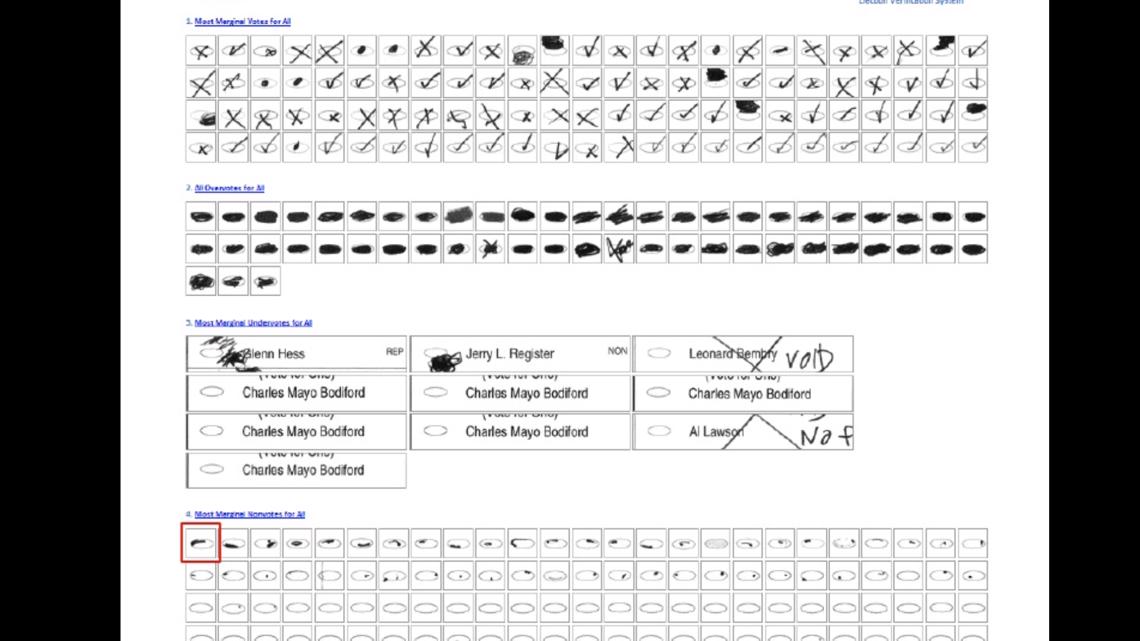

Ballots are hand-examined, and compared against computer records. The process ensures that bugs in election machines, dust-blocking ballot scanners or occasional software glitches are caught and no vote is inadvertently altered.

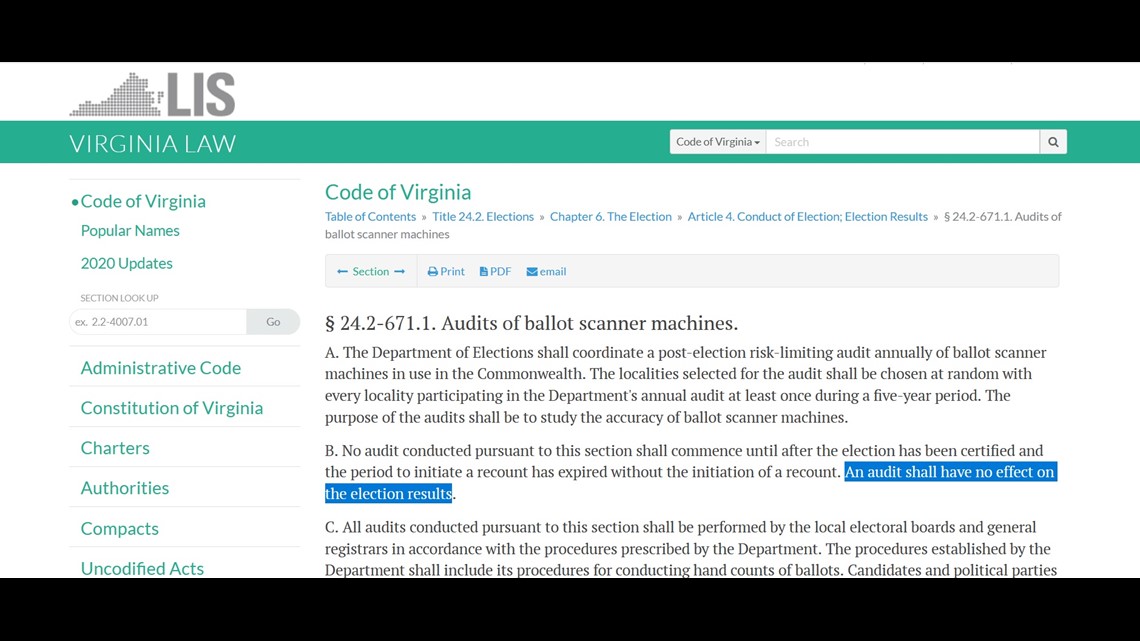

But in Virginia, this meticulous audit takes place only after the results of the November 3 election are certified. That means potentially erroneous election results cannot be changed. By state law, “an audit shall have no effect on the election results.”

RELATED: Voter Guide 2020: Everything you need to know about the elections in DC, Maryland and Virginia

As a worst-case scenario goes, a machine glitch might wrongly record votes –only to be discovered after the state had already certified election totals. For close and consequential races, voters may find machine errors identified too late in the process to be problematic or unacceptable.

By the letter of a law adopted in 2018, Virginia’s post-election audit does not cover the entire state. Localities are chosen at random after the election and after results are certified. The accuracy audit then begins.

Interviews and a review of Virginia’s risk limiting audits showed 1-in-5 localities across the commonwealth have implemented the post-election assessments since 2018.

Considerable resources and training are needed to perform the examinations. Virginia localities are now required to audit their election results at least once every five years.

In an interview, Virginia Elections Commissioner Christopher E. Piper declined to comment on whether risk-limiting audits should be performed when potentially incorrect results are still able to be fixed. Yet he signaled a willingness to move quickly if the state law were to eventually change.

“I take the position that I have to administer the law, and the law states that we don't do risk-limiting audits until after the certification of the election,” Piper said.

“And so, I think that if the General Assembly and the governor were to come together and require that [change], we would certainly work with them to make sure that it was implemented properly.”

Despite an advanced audit now powerless to change incorrect votes, Virginia ballot scanners are new, disconnected from the Internet, and have their functions tested before Election Day.

The commonwealth’s pre-election machine assessments, known as “logic and accuracy tests,” examine whether ballot scanners are operating properly. Yet these tests do not scrutinize how accurately machines scanned hundreds or thousands of ballots after a surge of Election Day votes.

A human error review of results begins when polls close, a process called a canvass. Rather than examining machines, a canvass largely assesses paperwork in order to flag human mistakes and arithmetic errors.

“This is just to make sure that poll workers have the math right, just to make sure that nobody transposed numbers, nobody accidentally added a zero or forgot a zero,” said Liz Howard, senior counsel at the Brennan Center and former deputy commissioner of the Virginia Department of Elections.

“But the canvassing process doesn't go back and look at the accuracy of the machine.”

Howard oversaw Virginia’s effort in 2017 to throw out all paperless voting systems, as the defunct machines were vulnerable to hacking. The hardware also lacked paper ballots, which serve as essential vote copies should an election require a hand recount.

Howard expressed faith in the strides Virginia’s localities have made to gradually implement risk-limiting audits and stressed that states like Delaware, Louisiana and Alabama don’t audit election audits at all.

Yet she said more can be done in the commonwealth; specifically, changes to strengthen the audit law.

“Can Virginia improve its current audit procedure? Absolutely,” Howard said. “And you know, in two ways I think that are very important, which are to conduct the risk limiting audit prior to certification, and to mandate that the entire state, all of the election officials across the commonwealth, conduct the audit at the same time.”

With three weeks before November 3, it remains unclear which of Virginia’s 133 localities will eventually audit their results for the consequential election. Piper said the cities and counties will be randomly selected at a date after the election.

Piper signaled preparations are being made to expand the audit system in time for Virginia’s 2021 elections, when the governor’s mansion and House of Delegates are in contention.

“The law requires that all 133 localities have to have done an audit within five years,” Piper said. “So, we anticipate that in 2021, we'll up that number quite significantly from the 29 that we've done so far. We want to do a lot more going into 2021.”

For comparison, in neighboring Maryland, all ballots and machine results are audited within the weeks before the state vote is certified.

Images of all ballots are sent to the Boston-based election technology company Clear Ballot for analysis in a matter of days. Clear Ballot reports its results to Maryland state officials and discrepancies are examined.

Howard noted the audit backed by Annapolis is not a true risk-limiting audit, since images of ballots are scrutinized, not the original ballots themselves. Digital ballot images run the small risk of being corrupted or potentially altered, Howard said, a technical point that excludes the method from the family of risk-limiting audits.

Like Maryland, Washington D.C. also audits its results before the vote is certified. Yet the audit is less expansive, examining at least 5% of precincts and 5% of votes centrally tabulated by the Board of Elections, including absentee and special ballots.

For Virginia, a WUSA9 Freedom of Information Act request seeking data on the number and magnitude of errors detected by risk-limiting audits is still pending,

Yet, Howard said it remains a matter of if, not when, the practice is more widely administered across Virginia. She described Virginia’s efforts as “ahead of the curve,” and said the efficacy of logic tests, canvassing, and updated voting machines, should see the process through.

“I think that the work that election officials have done and are doing is important,” Howard said. “And there are lots of reasons for Virginia voters to have trust in the election administration system in Virginia.”