WASHINGTON — On Friday, the Justice Department said it was focusing on the events at the U.S. Capitol Building on Wednesday, and that it had not yet charged anyone with incitement or seditious conspiracy charges connected to the “Stop the Steal” rally that immediately preceded the attack on the Capitol.

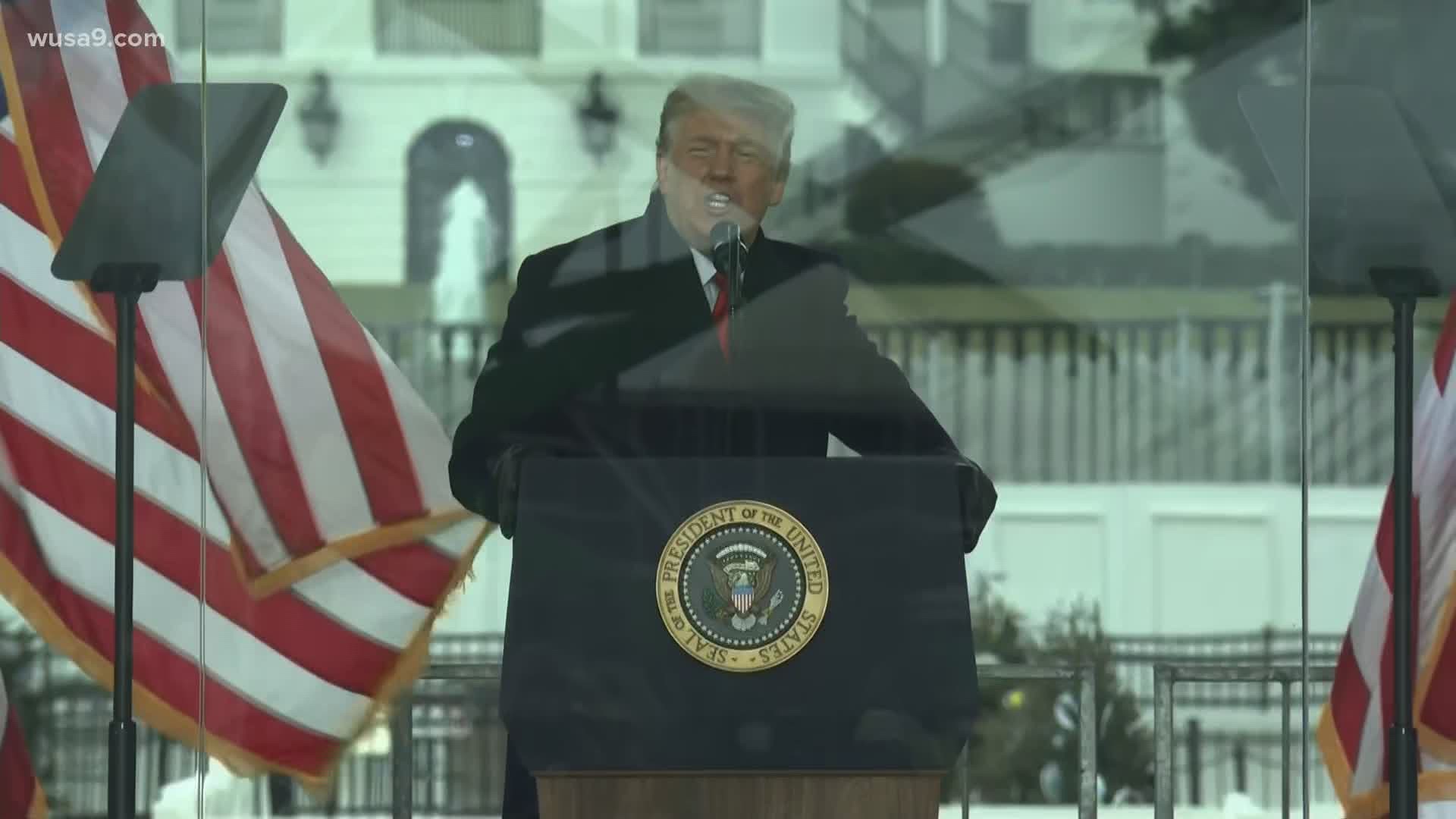

Those speakers included President Donald Trump’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani – who disputed the results of the November presidential election without evidence and called for “trial by combat” – and Trump himself, who vowed in front of the crowd of thousands of his supporters to “never concede," then urged them to walk down to the Capitol with the exhortation, "You'll never take back our country with weakness."

Thousands of those supporters then did walk to the Capitol Building, where a short time later they clashed with Capitol Police and ultimately breached the building, prompting the suspension of a joint session of Congress and a lockdown of multiple federal buildings. In the ensuing chaos, at least five people were killed, including a Capitol Police officer who died Thursday evening of injuries sustained during the event.

Although neither Trump nor Giuliani participated in the breaching of the Capitol, a George Washington University law professor said their involvement and speeches at the preceding rally could potentially amount to incitement and even seditious conspiracy under a memorandum written in September by then-Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen, now the acting attorney general.

The memo, sent Sept. 17 to all U.S. attorneys, was titled “Charging in connection with violent rioting, including 18 U.S.C. § 2384” – which is the portion of the federal code defining “seditious conspiracy.” At the time, Rosen said he sent the memo to re-emphasize instructions from then-Attorney General Bill Barr that prosecutors should consider sedition charges for individuals who committed violent crimes at protests. The memo, and Barr’s statements, were a response to months of Black Lives Matter protests across the country in the wake of the death of George Floyd.

The memo lays out in explicit language the sorts of actions that could warrant a sedition charge, including conspiracies “by force to prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law of the United States” or to seize, take or possesses any property of the United States. The memo makes clear that Section 2384 “does not require proof of a plot to overthrow the U.S. Government.”

The memo tells prosecutors specifically that they should consider a charge of seditious conspiracy “where a group has conspired to take a federal courthouse or other federal property by force.”

As of Friday afternoon, federal prosecutors had filed charges against 13 individuals in connection with the breach at the Capitol – none related to the rally.

According to George Washington University Law Professor Stephen A. Saltzburg, a former deputy attorney general with the Justice Department and an associate independent counsel during the Iran-Contra investigation, that’s not surprising.

“This Justice Department isn’t about to indict the sitting president,” he said. “Now, come Jan. 21, it’s a new Justice Department.”

The failure to quickly and aggressively employ the seditious conspiracy statute, as the memo suggests federal prosecutors should, is evidence, however, of unequal treatment by the department, Salzburg said.

“I actually think Bill Barr meant what he said. And I believe that if Bill Barr were attorney general, he would not say that we’re not bringing charges,” Saltzburg said. “On this one, I think he’d say charges should be brought. This is outrageous. I think most of his tenure was a great disappointment, if not a disaster, but the inconsistency here is that he meant what he said when all he could see were anti-Trump, anti-police, Black Lives Matter protestors. But now the Justice Department, just like the Capitol Police, treated this so much differently than they would have Black Lives Matter protestors.”

Saltzburg called the treatment of the June 1 Black Lives Matter demonstration in D.C. and Wednesday’s breach of the Capitol “night and day.” He’s not alone. As WUSA9 reported in June, federal police showed their willingness to use everything from grenade-launched chemical irritants to unmarked Bureau of Prisons riot control officers, and even a National Guard helicopter, to control and disperse crowds. DC Police arrested more than 300 people during a single night of protests.

By comparison, the Capitol Police arrested little more than a dozen people among the mob that broke into the Capitol Building. Tennessee Rep. Jim Cooper (D) has even suggested Capitol Police might be “complicit” in allowing the Capitol to be breached.

Even if the Justice Department – either this one, or a Justice Department headed by President-elect Joe Biden’s nominee Judge Merrick Garland – does decide to pursue incitement charges, it could be an uphill battle.

For one thing, the bar, set by the 1969 Brandenburg v. Ohio case, is high. That ruling established the imminent lawless action test, which says speech is not protected under the First Amendment if the speaker intends to incite a violation of the law that is both “imminent and likely.”

The bigger obstacle could be an unprecedented move by Trump to pardon himself.

“Many of us assume by then the president will pardon himself,” Saltzburg said. “I think he’ll not only pardon himself, but also family members as well. I think he’ll potentially pardon the other inciters, Rudy Giuliani, Michael Flynn… interestingly, he’d have to pardon Flynn again, because Flynn’s pardon is only good up to the day he accepted it.”

The possibility of a self-pardon has been broached by Trump himself, who tweeted on June 4, 2018, that he has “the absolute right to PARDON myself.” Trump was permanently banned from Twitter on Friday after the company determined his account posed a “risk of further incitement of violence.”

If Trump does pardon himself – and Saltzburg said he expects to see a “slew of pardons” in the coming days – the Justice Department would have to make an unprecedented challenge to that power, which would require adjudication by the U.S. Supreme Court. Ultimately, Salzburg thinks the Supreme Court would rule against Trump.

“I think most scholars believe that a president cannot pardon himself," Saltzburg said. "That has certainly been the Justice Department’s position. It would mean the president is totally above the law. But I think he’ll try.”

The most likely scenario, Saltzburg said, is that the Justice Department will wait to make its decision on incitement charges until after the Congressional investigation into the Capitol breach is complete and until the cases against Trump pending in New York have resolved.

“I expect that they won’t do anything until the New York matters have a chance to play out,” Saltzburg said. “As I read it, (New York County District Attorney) Cy Vance is looking at bank fraud, tax fraud, lying and campaign fraud like the Michael Cohen thing. So, there’s a lot of stuff there.”

If no one is ever charged with inciting the Capitol breach, however, Saltzburg said it will assuredly repeat itself.

“The idea that nobody will be prosecuted for inciting this means that it’s an invitation for it to happen again,” he said. “And this country, I think, can’t readily afford to go through this another time.”