It emerges from tissue cells in the brain itself, spreading like an interlocking network of tiny fingers with such speed that pinpointing treatment is chasing a moving target.

It stimulates the abnormal growth of blood vessels around itself to assure it is well fed. And even if the main body of cancerous tissue is removed and the patient is treated with radiation or chemotherapy, a few hard-to-reach cells multiply, divide and grow stronger.

Then the whole process starts again.

This is glioblastoma, the most aggressive of all tumors originating in the brain.

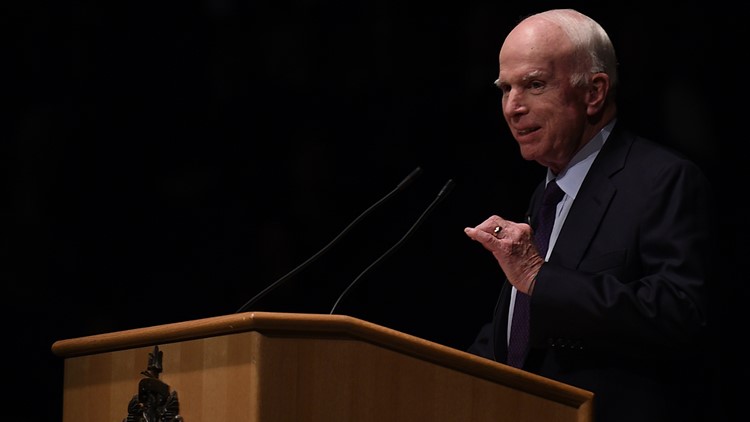

And though researchers have moved forward during the past decade in understanding this deadly brain tumor, the type Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz. died from, remains incredibly difficult to halt.

Understanding improves, but progress slow

There has been little progress in developing new U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs since McCain’s former Senate colleague, Ted Kennedy, succumbed to the same type of brain cancer in 2009. And it remains deadly: Half of patients with glioblastoma die within 15 months.

Nonetheless, doctors are constantly testing new drugs and drug combinations to slow the growth of these tumors after standard treatments of radiation and chemotherapy have failed.

“I think our understanding is better than it’s ever been,” said Nader Sanai, a neurosurgeon at Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix and director of its Brain Tumor Research Center. “Obviously, this (McCain's) is a similar situation to Senator Kennedy's. That was 10 years ago and the field has advanced, though in this day and age, it’s still difficult.”

Medical researchers are pressing ahead with clinical trials testing dozens of drugs, drug combinations and unique methods of delivering therapies to tumors. In Arizona alone, there are 13 clinical trials recruiting patients with glioblastoma, according to the federal government’s ClinicalTrials.gov website.

One of the foremost problems: Finding a workable drug that can reach the tumor. The brain is protected by a membrane called the blood-brain barrier that protects it and the central nervous system.

“Most experimental drugs are ineffective in reaching the area of the brain that you need to reach,” said Sanai. “The brain is designed to keep drugs out.”

Using the immune system to fight tumors

One emerging area, immunotherapy, includes therapies that prod the body’s immune system to attack the tumor. This type of therapy has been used to fight other types of cancer, and researchers are testing whether it would work in the brain.

A type of immunotherapy is chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells that are genetically engineered to attack glioblastoma. Duarte, Calif.-based City of Hope last December reported in the New England Journal of Medicine that doctors used this therapy on a 50-year-old man with glioblastoma.

The man's brain cancer had returned six months after being halted by an initial round of surgery, radiation and the chemotherapy drug temozolomide.

"When he came to us, he had many tumors on his brain," said Behnam Badie, City of Hope's chief of neurosurgery and director of its brain tumor program. "Survivability was really, really dim. You are talking weeks."

Doctors injected genetically engineered CAR T-cells into the patient's brain, and his tumors regressed for nearly eight months. However, tumors later spread and the patient died this spring.

City of Hope, which is affiliated with the Phoenix-based Translational Genomics Research Institute, or TGen, has enrolled about 20 patients in the study, Badie said.

"It's not curative," Badie said. But, he added, "We are definitely seeing changes in the biology and extending lives."

'Cautiously optimistic' about 'poliovirus' study

Other approaches that have received widespread attention include Duke University's "poliovirus" study that uses a modified version of the polio virus to enter glioblastoma and attack the cancerous cells from within.

Duke's first clinical trial enrolled 61 people with the brain tumor after initial radiation and chemotherapy failed. Of those, 20% have survived at least two years and two people have survived more than five years.

Duke's study team is "cautiously optimistic" about the phase one study's results, considering half of all patients with glioblastomas that return after initial treatment die within eight months, said Henry Friedman, a neuro-oncologist and deputy director of Duke University's Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center.

"Obviously, we are not going to jump up and down when we have an 80% failure rate," Friedman said.

Duke has launched a follow-up study of the poliovirus treatment combined with the chemotherapy drug lomustine.

'Phase zero' trials address barriers

Barrow Neurological Institute, meanwhile, has launched a “phase zero” study that aims to rapidly test drugs on patients whose brain cancer tumors have returned after standard treatment.

While conventional clinical trials study drugs over several years, Barrow’s program seeks to quickly test experimental drugs within months.

In this regimen, doctors give patients drugs hours or days before a surgery. When a tumor is removed, doctors analyze the genetic profile of the tumor and evaluate whether the drug penetrated cancerous tissue and slowed its growth.

Sanai said the phase zero trials seek to address two of the main barriers to developing new therapies: verifying that drugs have reached the tumor, and ensuring that the tumors have responded to the drugs.

The latter is an obstacle in brain-cancer research because experimental drugs that are first tested and show promise in animals might not work in humans. Scientists often assume that a tumor should respond to a drug based on success in early tests in animals. But human brains, brain tumors and genetic signatures are far more complex than what scientists are able to study in animals, Sanai said.

Barrow has tested multiple drugs as part of its study, which has enrolled fewer than 100 patients.

"Currently, what you are hearing about most is immunotherapy," Sanai said. "These trends come and go. In the end, the fundamental problems always boil down to those two issues" — drugs reaching the tumor, and the complexity of human tumors compared with animal tumors.

'Just never give up'

The Ben and Catherine Ivy Foundation in Arizona has funded several brain-cancer research efforts at TGen and other research institutions. Catherine Ivy launched the foundation in 2005 after her husband, Ben Ivy, was diagnosed with glioblastoma and died four months later.

Ivy said her foundation remains committed to supporting brain-cancer research efforts, including new diagnostic tools that can improve treatment.

She said she was saddened by McCain's diagnosis, though she also had some advice for the Arizona senator and his family.

"Just never give up," Ivy said. "There's a strong community of people working very hard to conquer this disease."

This article was originally published in 2017.