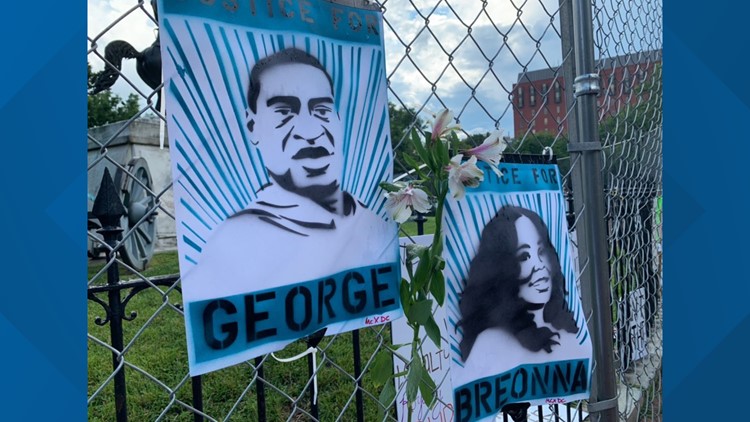

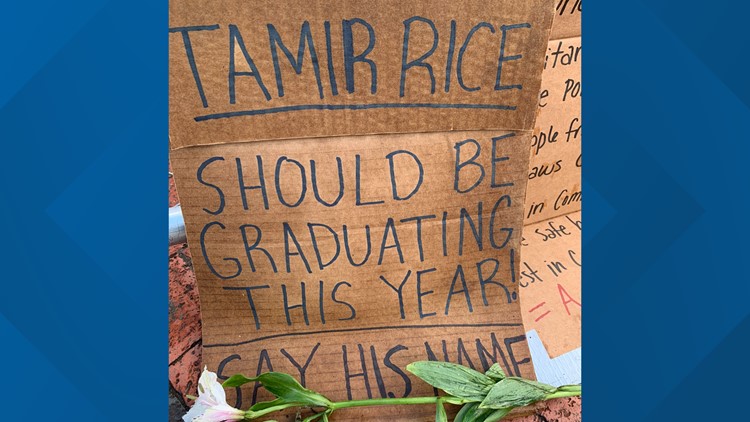

WASHINGTON — It's been exactly five weeks since the initial protests against police brutality began in the District, exactly one month and one day since George Floyd died under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer.

On that Friday, May 29, the streets of D.C. were busier, entangled with construction signs demanding police accountability and chants shouting 'No Justice, No Peace". But it was just past 11:30 p.m. when the tensions would bubble over, ultimately turning the night into the first of many where Lafayette Square would be filled with tension and standoffs between police and protesters.

As the weekend carried on, chaos erupted. Pellet bullets, pepper spray and confrontations between law enforcement and demonstrators lasted past 4 a.m on both nights. The Third Amendment, the one that prevents soldiers from quartering inside your home, would trend on social media after a D.C. resident sheltered dozens of protesters in his K Street home.

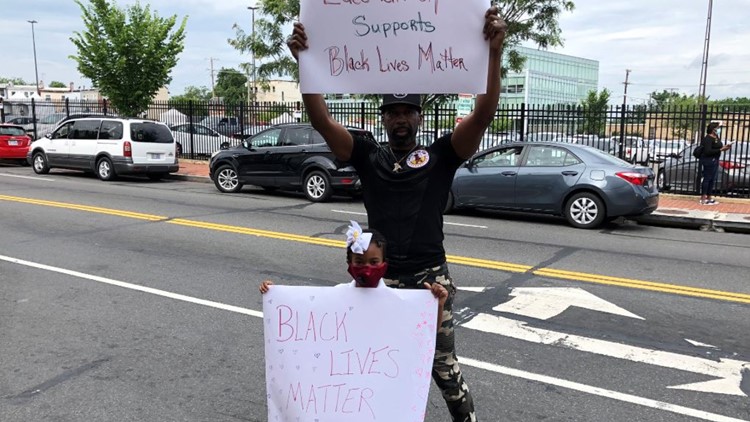

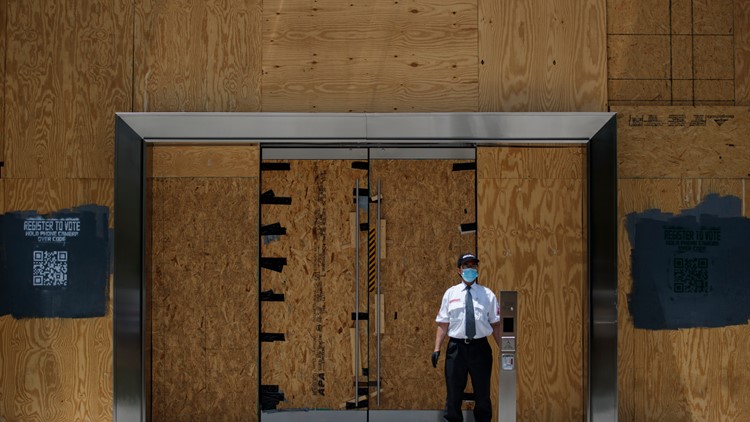

In the weeks that followed, life in the District was far from quiet. More than 5,000 National Guard troops would be called in to patrol Pennsylvania Avenue and other areas of the city, low-flying helicopters were heard despite a city no-fly zone. Protests became the daily norm wavering between highway shutdowns and tear gas to prayer vigils and peaceful singing.

Protests and demonstrations aren't unusual in D.C. They're the backbone of what makes the District so vastly unlike any other spot in the country. It's not just the capital of the nation, but the backdrop to where demands for change carry, then land, at the stairs of the Supreme Court, in the hands of lawmakers, and on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The 68.31-square mile place that takes the frustrations of the country and mirrors it back in capital letters and toe-to-toe standoffs with the White House.

While the number of protesters has dwindled, the focus seems to have shifted away from the volume of people gathered to the restored energy emanating from those who are left.

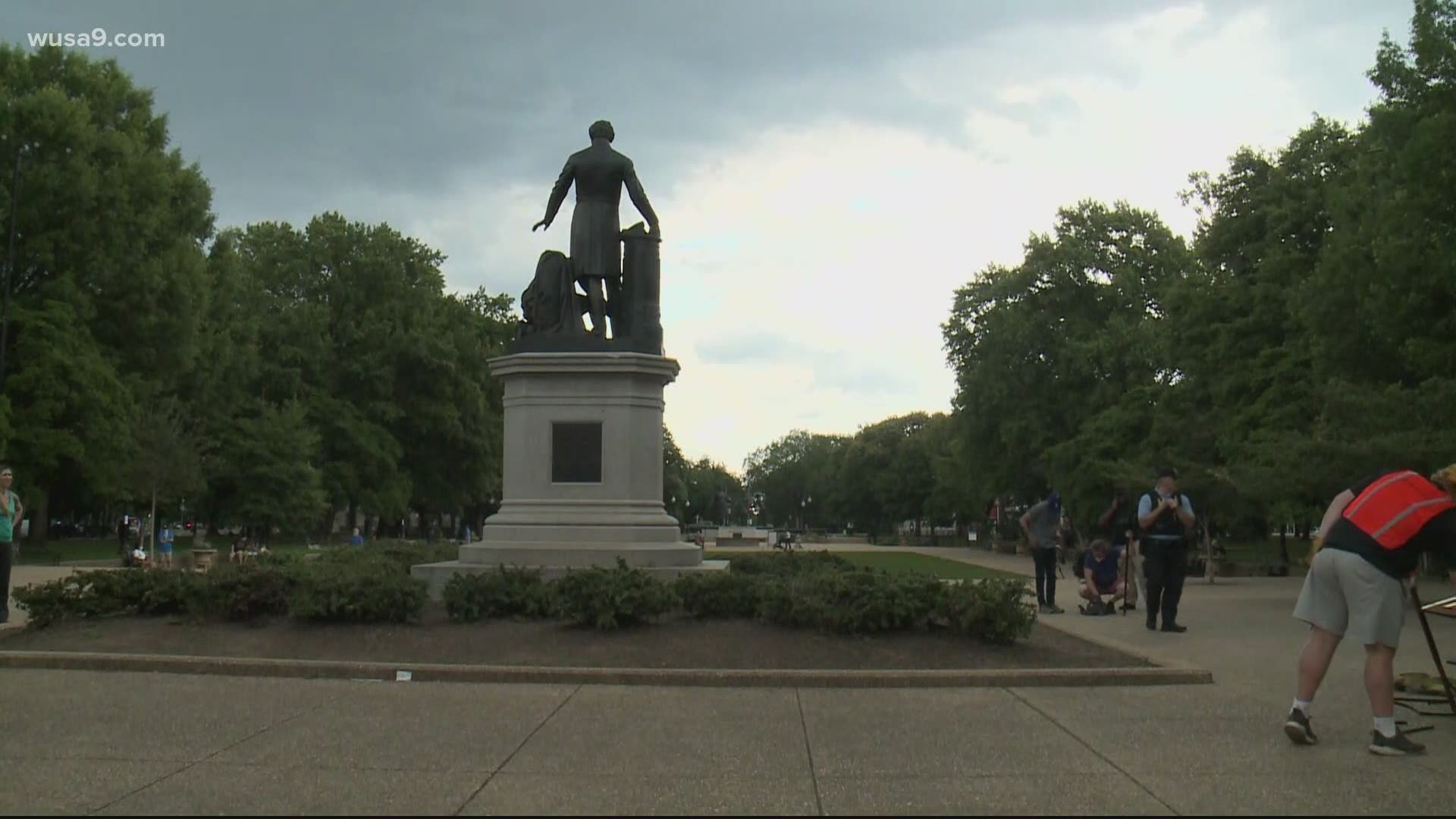

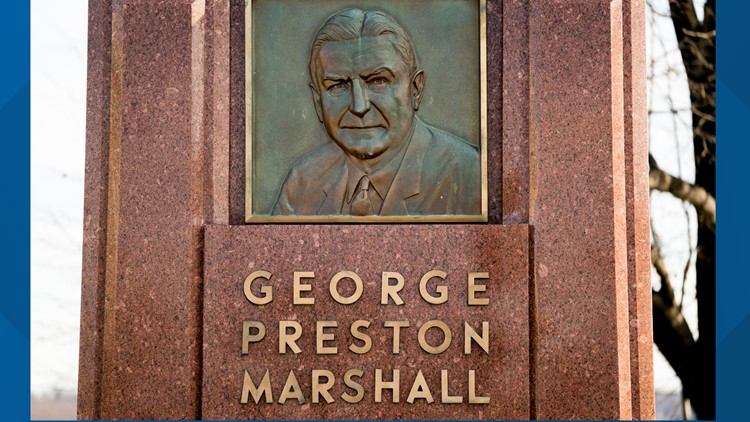

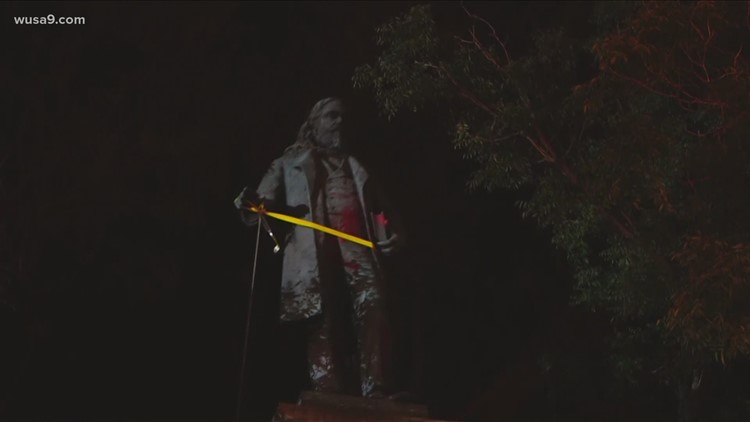

Tonight, a group of demonstrators rallied at the Emancipation Memorial to engage in a conversation on race. They stood in Lincoln Park to call for the removal of the statue depicting Lincoln and a freed slave. It's one of many memorials that activists say need to come down, including the recently torn down statue of Confederate General Albert Pike.

Rather than protesters with ropes and gasoline ready to topple and torch, tonight we see a Frederick Douglass impersonator who stopped by to "give historical context" to the conversation, and an artist painting side by side portraits of Abraham Lincoln and Archer Alexander, finally meeting on the same level.

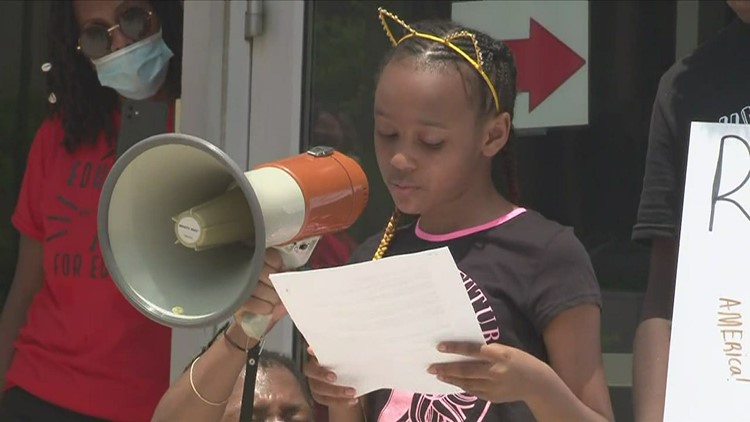

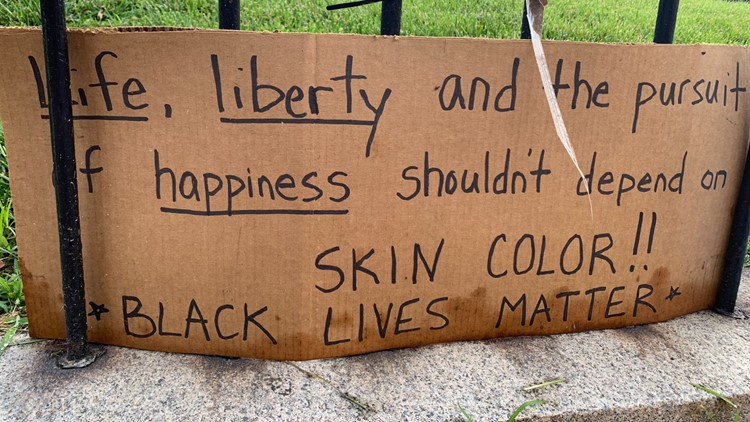

"I would not put these people on pedestals, I would bring them down here," one man says into the microphone, pointing towards the crowd gathered at the base. "I would tell the story in this park. Have you all been listening to the stories? That is the thing that I think has been missing through all of this -- why Black Lives Matter. And that conversation is so important."

"Because it is a conversation," he continued. "And we should be listening, all of us. Are you?"

Perhaps all of that, the protests and the gathering for change, the month of renewed passion and clashes of violence on District streets is in of itself a temporary, unofficial monument. One created in repeated attendance and photographed for years to come, both a historical commentary and a culminated vestige of a turning point in the country.

RELATED: From unrest to joy, DC's week of George Floyd protests made space for a spectrum of emotions