FAIRFAX COUNTY, Va. — When people call 9-1-1 during an emergency, they typically expect a police officer to rush in and help. But who do police officers call for help?

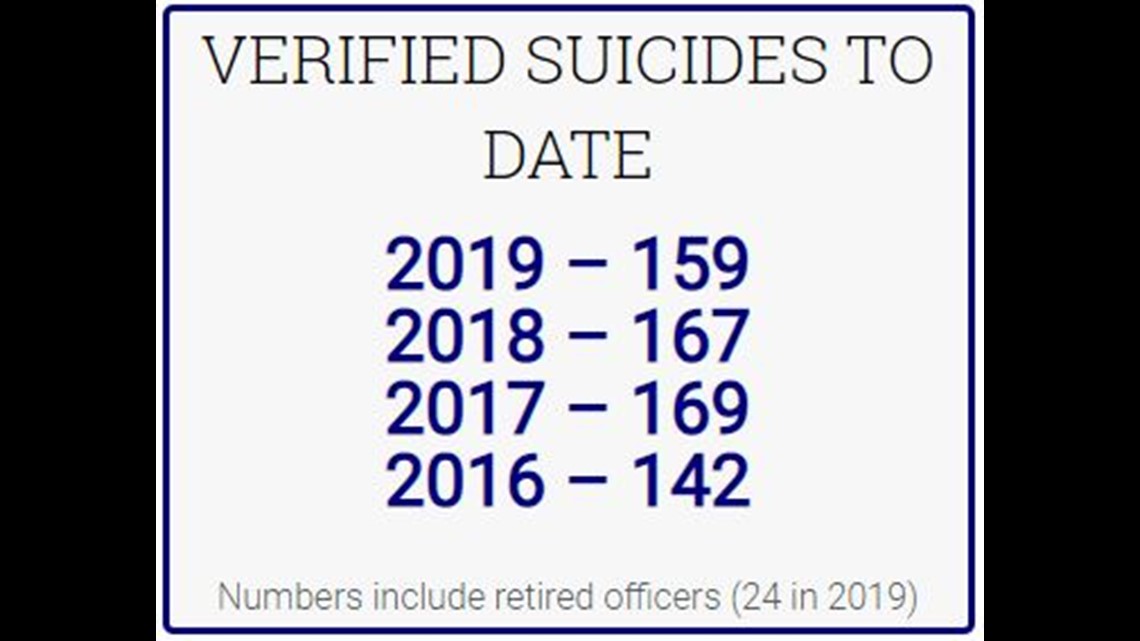

Across the country, there’s an epidemic of police officer suicides. An estimated 167 officers took their own lives last year. Steve Casstevens, the president of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, said this year is on track to be even worse.

"Every day is a recovery," Master Police Officer Adam Stone, who has been a cop in Arlington for 30 years, said.

Stone loves his job, and he’s doing his best to help others by telling his story After contemplating suicide, Stone is on medication and receiving counseling -- and still on patrol.

The 9/11 terrorist attacks were a trigger for his mental crisis. Stone rushed into the Pentagon parking lot to help save lives. But he said the destruction, personal problems and the sexual abuse he faced as a child left him struggling.

"I walked into the bathroom with a pistol," he said. "I can almost feel the end of the pistol at my head, and visually see myself pulling the trigger and falling to the floor."

Stone said he stopped himself and his wife rushed in and wrestled his gun away. He voluntarily checked himself into a hospital for a five-day stay.

Police officers right now are far more likely to die at their own hand than at someone else’s. They're far more likely to die by suicide than by heart attack or traffic accidents, according to police suicide data from Blue H.E.L.P, a prevention group, and other police death statistics from the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund.

It’s the number one issue for the new president of the International Association of Chiefs of Police.

"I have more confidence in a police officer who asks for help and gets it than a police officer who needs help and doesn’t ask," Chief Steven Casstevens said.

Suicide rates have been climbing for all Americans. But experts say police officers' chronic exposure to death, trauma and crisis may make them especially vulnerable.

Of about 18,000 police agencies around the country, fewer than five percent have suicide prevention programs for their officers, according to a 2018 study from the Ruderman Family Foundation.

After the suicides of several of his officers, Fairfax County’s police chief made prevention a huge priority: With full-time, in-house counselors and a commitment that a broken brain will be treated much like a broken bone.

"Back in 2010, I realized certain things in my life have accumulated, and I went and sought help and treatment," Fairfax County Police Chief Edwin Roessler said.

Roessler struggled with mental health issues, but it didn't keep him from rising to the top of his department.

"Every day is a struggle," he said. "Everyone struggles. You just have to admit it. There’s no shame in it."

New York City is among the communities hit hardest. Its suffered nine suicides so far this year -- including a deputy chief. But psychologist and retired NYPD detective Thomas Coughlan remembers how reaching out for help saved one of his patients.

"And he said, ‘If it wasn’t for you and it wasn’t for this program, my son wouldn’t have a father. He would never know me,'" Coughlan said, describing one counseling session.

Retired Norfolk investigator Chris Scallon was in D.C., getting an award for National Police Officer of the Year when he considered suicide. Years of crime scenes and shootings had pushed him over the edge. Scallon changed his mind just before pulling the trigger -- ashamed of what his friends might think of him if he’d gone through with it.

He said the message here is clear: With peer support, police chaplains and psychologists, police departments can save lives not just of the public, but of their own officers.

"I’m no more embarrassed by my diagnosis than I would be if I had cancer," Scallon said. "It's just a health issue, and you can recover from that."

In Arlington, Stone said his police department has done a lot to help him too. He’s convinced his crisis has made him a better, more empathetic police officer.

"The biggest message I can put out is number one, there is help available," Stone said. "Number two, you’re going to get through it."

It’s a message more and more departments are working on. Advocates said the only way to deal with this issue is for police chiefs and their departments to make it a priority: To fight the stigma, the sense that troubled officers are letting everyone down and to send out a message that help is available.

You can reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-TALK (8255).