WASHINGTON — We’re celebrating two big dates: Black History Month and WUSA9’s 75th anniversary – which we’re marking all year. A profile of legendary WUSA9 broadcaster Max Robinson brings both together.

Max Robinson never wanted to be called out as the first anything. He just wanted to do the job.

“I had a lot of doors slammed in my face by people who were really indignant that someone of my color would even get into something like this, you know," he told an interviewer in 1978.

Robinson was a trailblazer. The first Black local anchor in the country, and later on ABC, the first African American to anchor a national network newscast.

"I’m a little kid, and I wanted to be a newsman, and I look at the TV as a kid and see someone who looks like me," said Wisdom Martin, co-anchor of WUSA9's morning news, Get Up DC, who remembers watching Max Robinson as a child. "Without Max Robinson, there is no Wisdom Martin. So every time I walk in the door, every time I sit in that chair, I think about all that Max Robinson did," he said.

WUSA9 sports anchor Chick Hernandez also watched Max Robinson, as he was growing up in Silver Spring, and remembers asking his mother: "How does that happen? How is there a Black man doing the news?"

Hernandez says it gave him a sense that he could be on the news too.

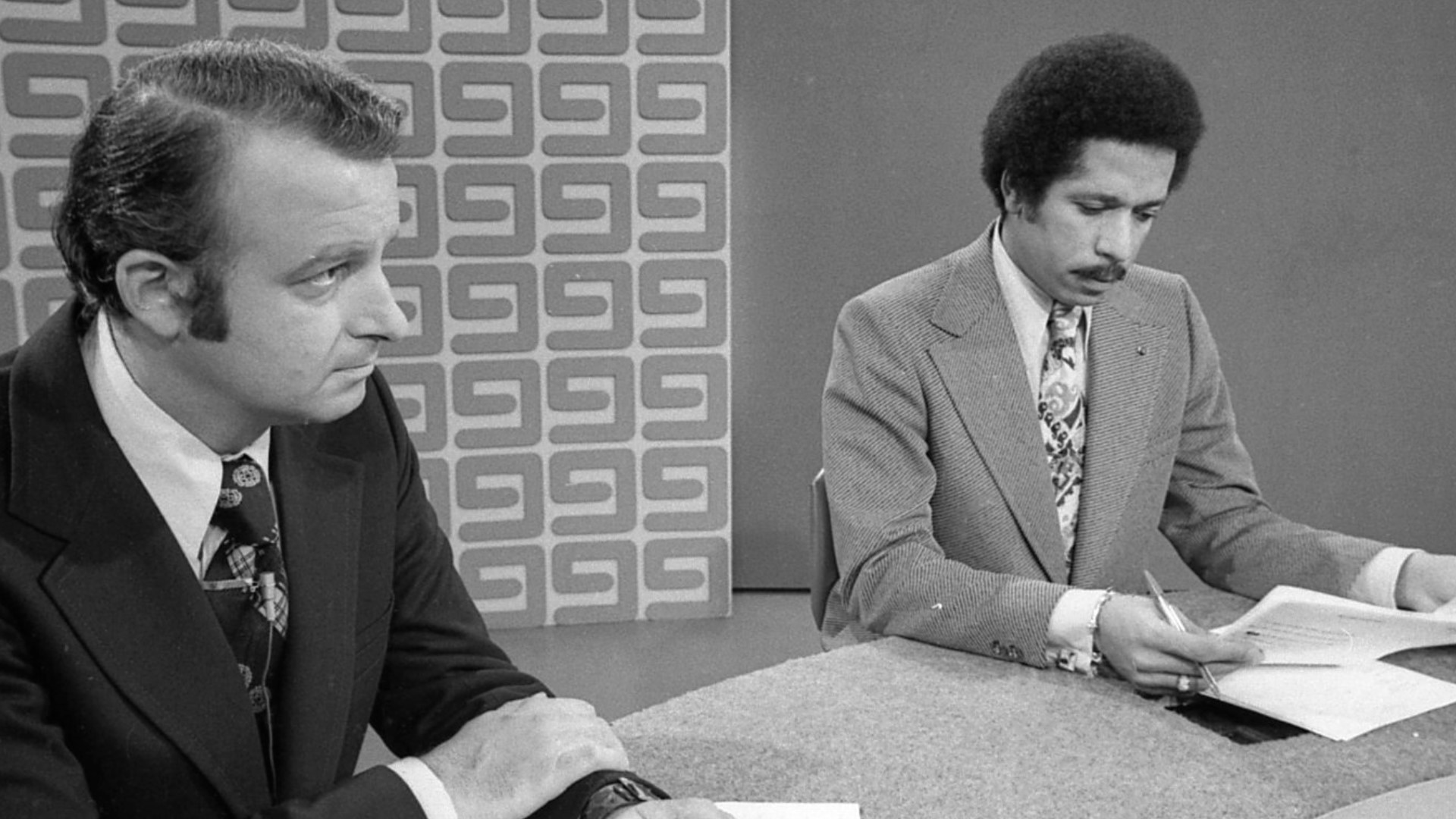

"To see the opening of the show and Max Robinson, Gordon Peterson, are you kidding me, there’s nothing better than that."

At his funeral in DC in 1988, one mourner called him, "the Jackie Robinson" of broadcasting.

Robinson started in television at a Portsmouth station in 1959. He read the news with his pitch-perfect voice, but his face was hidden behind a slide with the station’ logo. One night, he decided to go on camera. The next day, his boss fired him.

He started at Channel 9 in 1965 as a floor director. Then did a stint at another station as a reporter, winning an Emmy for a documentary on living in Anacostia.

"Our story is not so much about Negros and poverty," he intoned in his deep, stentorian voice, standing beside the river, "as it is about poor Black people living on the outskirts of society."

"Incidentally, this whole time, I'm making $50 a week. Very difficult. I had a wife and two children," he told anchor/reporter Susan King in 1978. "Things have changed though?" she asked. "Yes, I have four children," he responded, and they both laughed.

He came back to Channel 9 as an anchor in 1969. eventually pairing with Gordon Peterson to dominate the ratings for years.

His oldest son, Mark Robinson, remembers those years. "People would just like, shout out, hail him on the street. You know, 'Hey Max! How you doing?' 'How you doing?'" he'd respond. "Hey Dad, you know that guy?" his son would ask. "Never saw him before,” Robinson would tell his child.

Mark Robinson is a newspaper reporter and cartoonist in Alaska now and promotes his father's memory on Facebook. He admits It was intimidating to be the son of a legend.

When Hanafi Muslims terrorized D.C. for three days in 1977, seizing three buildings, taking 149 hostages, and killing two people, Robinson reported from their headquarters. “Hamaas Khaalis is not here today," he said of their leader. "He’s barricaded in the B'nai B'rith building,” he told viewers as a man marched back and forth with what looked like a rifle behind him.

Khaalis later called Robinson live on the set with his demands. “You are asking that those who killed your children be brought to the Bnai Brith building?” Robinson coolly asked the hostage taker.

But then Khaalis threatened to abduct Robinson. “I’m going to be kidnapped by the Hanafis,” calmly said, looking straight into the camera.

But his was a life of both talent and torment.

“I heard it was pretty tough at the beginning at ABC?” interviewer Henry Tenenbaum asked him in a story for the old PM Magazine show. “Ugh," Robinson responded, putting his head in his hands. "One of the critics said, ‘There are no ghettos in the cornfields,’” Tenenbaum said. “No, it was an anchorman who said, ‘I don’t know how well a Black anchorman will relate in the wheat fields of Kansas.' It was one of the most absurd statements I’ve ever heard in my life, and I felt sorry for him, I really did,” said Robinson.

Robinson struggled with substance abuse and missed work for long stretches. He fell sick with complications connected to AIDS.

"He was wrestling with demons most of his life. And it was a sad thing to watch for those of us who loved him," said his former co-anchor, Gordon Peterson, after his death.

Just weeks before Robinson died at Howard University Hospital at 49, he spoke to a group of communications students at Howard University.

"I'm not recommending that you be an old hard head, like I was, stubborn. I never recommended my way, I did the best I could. But try to keep your integrity, because you're going to find out in life at the end, that's all you got," he told them.

Robinson found some solace as a painter. And as another reporter said after his funeral: Max Robinson was a man who lived his life as he painted. In bold strokes. His way.

Robinson’s legacy continues. Last year, Whitman Walker Clinic, which was at the forefront of fighting the AIDS epidemic, opened the $30-million Max Robinson Center east of the river at St. Elizabeth’s.

One patient said, ‘The name tells you all you need to know about who they are. They take the stigma out of your condition.’

In case you missed it, this year marks WUSA9’s 75th anniversary. We will be honoring our station's past throughout the year, with retrospectives and a look at some of the men and women who made us what we are today.