POTOMAC, Md. — African American history, once forgotten, is now a mission for descendants of a 150-year-old Black cemetery in Montgomery County.

“You can see there’s a stone here,” said Cherisse Crawford, who lives in Potomac. “There’s stones on top of stones here.”

In the 1800s, headstones were often just that. Stones. Especially for the grave of a former enslaved person or even a freed Black person.

“From babies to elderly people,” Crawford said. “Buried out here.”

Historic Union Wesley Methodist Church cemetery is hidden in a wooded area off Piney Meetinghouse Road. It is a place Crawford finds family. And frustration.

“There’s been no progress,” Crawford said. “There’s been no progress at all.”

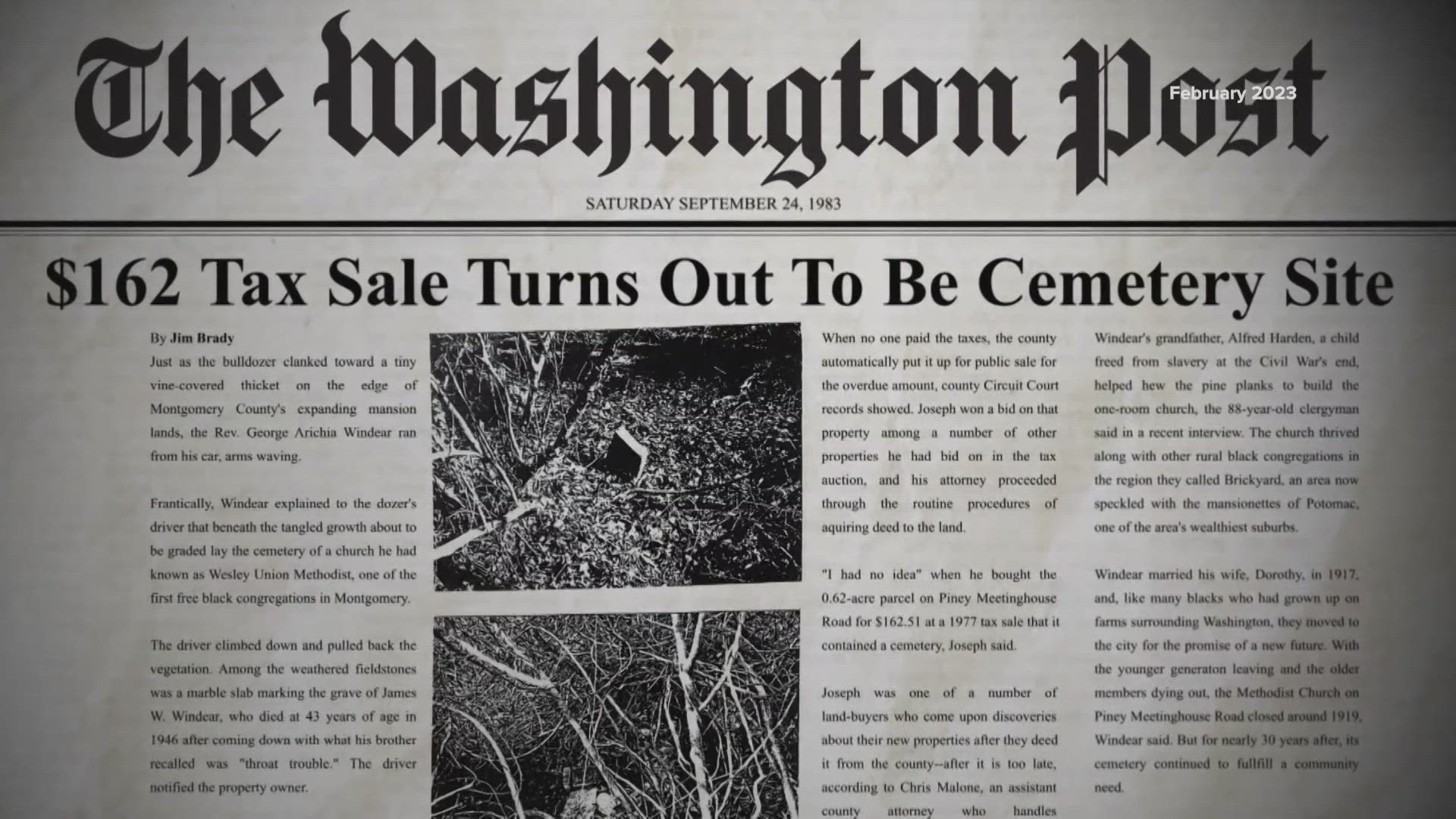

WUSA9 first reported Union Wesley Methodist Church cemetery in February 2023. An unknown number of former enslaved people and freed Blacks were laid to rest underneath the brush and debris that now covers it.

That includes Crawford’s great great great grandparents, Nelson Cooper, Sr. and his wife, Louisa.

“I just feel like I need to make it right,” Crawford said. “I feel like they didn’t deserve this. My family didn’t deserve this.”

A WUSA9 Investigation revealed Montgomery County auctioned off the land the cemetery sits on in 1975, but did not know the cemetery was there when it sold the property to a developer for $162 named Saul Joseph.

The land was then passed down to his son, Jeff Joseph, who still lives in Potomac and after realizing the location’s significance, left it undisturbed in the event descendants of those buried there one day stepped forward.

Which is what happened when Crawford knocked on Joseph's door in December 2022, and he pledged his support for the cemetery’s restoration.

Documents show Montgomery County realized the land was a former cemetery at least 2018, when a county preservation survey listed the condition of the burial site as “...poor, overgrown and neglected. With no signs marking at least 10 uncarved field stones and one broken hand-carved marker.”

Crawford believes many more graves than that lie hidden.

In March 2023, a month after WUSA9 original report, Dale Tibbitts, Special Assistant to Montgomery County Executive Marc Elrich, pledged to act.

“We have a history that we have to reckon with,” Tibbets said. “And we have to respect that.”

But a year later, Union Wesley Methodist Church cemetery sits in the same condition it did when Cherisse first showed it to WUSA9.

But now she’s not the only one fighting to save it.

“The only answer I got is God,” said Tracy Holsey, who also has ancestors buried at Union Wesley Methodist Church cemetery.

When Crawford told Holsey what she was doing, he was floored. Holsey is working on a book about his own family’s history in Montgomery County. Which, as it turns out, is Milliner’s family also.

“And when she got in touch with me and told me what she was doing, you know it just closed the chapter on things I never knew I’ve been looking for,” Holsey said.

Which means, it’s not just her long-lost ancestors buried here. His are too.

“And I had no clue,” he said. “It was right here.”

Holsey called his childhood friend David McKenzie, owner of the fencing company Capital Fence.

“It’s wrong what’s being done,” McKenzie said. “The county should really help them clean it up, and they’re not giving them any help.”

“I told him what was going on,” Holsey said. “I didn’t have to ask him. When I told him what was happening, he said, I’m there.”

McKenzie offered to do the work free of charge.

“We can come in with plenty of equipment and grub down the trees,” McKenzie told Crawford and Holsey as they stood and planned work on the cemetery site.

McKenzie even offered to donate fencing to keep the historic cemetery preserved once it’s restored.

“By the time we’re done their families can come sit and talk to their relatives,” McKenzie said.

Only bureaucratic red tape in Montgomery County was preventing that, too.

Tibbets spent months blocking Crawford, Holsey and McKenzie from moving forward with their clean up, because Tibbets said the work might require sediment control permits and a land survey first.

After WUSA9 continued to press Tibbets, in February 2024 Tibbets relented.

In an email, Tibbets wrote to Crawford, “I checked with DPS (Montgomery County Department of Permitting Services) and a sediment control permit is not required. You are not exposing 5000 sq. ft. of raw dirt.”

Tibbets said the county’s survey of the land had still not been completed, but told Crawford “You can proceed with the cleanup you described with Mr. Joseph's permission.”

And now, a broken past can slowly be put back together by a determined present.

“This stone here it says, ‘gone but not forgotten’,” Crawford told the group.

“We’re here to make sure they’re not forgotten,” McKenzie added.

Tibbets did not respond to WUSA9’s specific questions about whether all the bureaucratic delays in getting this work started could have been avoided.

Councilmember Andrew Friedson, who represents the area and visited the cemetery site with Crawford and Jospeh, told WUSA9 in an email “I share in their frustration” over those delays.

Editors Note: In past coverage of this story WUSA9 referred to Cherisse Crawford as Cherisse Milliner. Milliner’s name has since changed to Crawford.