How a millionaire hacker and his fear of nuclear attack led him to become an unintentional killer

An in-depth look at the bizarre case of Daniel Beckwitt and the death of Askia Khafra, a man hired to dig tunnels underneath a home in Bethesda.

A crowded courtroom on the seventh floor of the Montgomery County Circuit court fell silent on Monday morning, as the family of 21-year-old Askia Khafra filed into the front row.

Their son had died in a house fire on Danbury Road in Bethesda, almost two years prior.

In the days and months that followed, as more details revealed themselves, the circumstances of how exactly young Askia Khafra had passed away grew increasingly strange.

It all culminated on that Monday - June 17 - when a judge sentenced the man blamed for his untimely death, Daniel Beckwitt, to nine years in prison and five years of probation.

The Hacking

It wasn’t the first time Daniel Beckwitt had been in trouble with the law.

After an unusual upbringing as a homeschooler, he went to the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana and struggled to make friends.

“If you got a chance to know him, he’s a nice guy,” his own lawyer said at his sentencing. “He’s just weird, in his own way.”

When he went to school at the University of Illinois, Champaign-Urbana, he struggled to make friends.

“He was really smart but didn’t have a lot of social concepts, you know?” a friend of his from the university said. “He just didn’t understand like the social concepts, meeting people, and talking to them.”

Never a standout student, his friend (who asked to remain anonymous) said Beckwitt didn’t care much for classes, and rarely went.

The friend explained once Beckwitt’s mother died and his father got sick, it was a turning point.

He said Beckwitt had spent time previously on internet forums, but his parents had encouraged him to spend less time online.

“I know his parents told him not to do that kind of stuff,” he said. “They were really the guiding light in his life.”

The Verge reported Beckwitt found some success as a hacker, and presented research at security conferences like DefCon and SchmooCon.

Eventually, Beckwitt was arrested for his role in a hacking scheme - where he was accused of sending emails from another student’s account, placing “keyloggers” on computers in a computer lab that recorded information of people using those public computers - and impersonating a professor to email students their final was canceled, when it was not.

“It was an elaborate attack on the University of Illinois’ computer engineering department,” prosecutors said Monday. “It went on for months and it was calculated.”

The student newspaper reported he served 24 months probation, paid more than $2,000 in fees and court costs, and $22,793.32 in restitution to the University of Illinois.

His college friend said he wasn’t surprised by that case in the slightest, and it seemed as though he had not learned his lesson. But, he said, Beckwitt didn’t set out to kill Khafra.

“In my heart, I know Dan did not intentionally try to murder that kid. Dan was just sloppy. I know he was doing something stupid, like daisy chaining extension cords,” he said. “I think it really was just a stupid mistake. But sometimes you just make stupid mistakes and lives change and you end up in jail.”

The Fire

“The day of the fire, I heard screaming and raced up here” WUSA9 reporter and Beckwitt’s neighbor Bruce Leshan recalled of the day the home caught fire.

“Someone is screaming and I can see smoke coming from the house,” Leshan said in his call to 911 as he ran to the home. “I heard somebody screaming.”

The smoke was coming from under the eaves, about ready to come out, he told the dispatcher.

“Is anybody in there?” he shouted to the home. “Come on out, come out of there.”

Later, he said it was one of the most terrifying days of his life.

“I was working outside and I heard somebody screaming in a deep loud voice, get out, get out, get out!” he reflected. “It sounded like someone yelling at his dog or something.”

He said he ran to the front door and pushed it open, when smoke came pouring out of the home.

He said he saw Beckwitt come around from the side of the house, and the neighbors peppered him with questions, like if anyone else was inside.

“He paused for a minute and said ‘Yes, there is somebody,’” Leshan said.

Leshan said he ran around to the side of the house, pushed the door open and stuck his head in to see if he could help. He shouted into the home, but didn’t get a response.

“I could see just flames inside the house but nobody answered,” he recalled. “Daniel said at some point, ‘He’s probably already dead.’”

The Interview

As investigators tried to piece together the details of this bizarre case, they learned more about the relationship between Beckwitt and Khafra.

On Sept. 13, 2017, Beckwitt sat down with authorities to give his side of the story.

“I just want to get this all cleared up,” he said.

Beckwitt revealed he and Khafra met on Blab.IM -- a live video-streaming platform -- about a year prior to Khafra’s death. The two hit it off and decided to meet in person in summer 2016.

Despite only referring to Beckwitt as “3Alarm” -- a shortened version of Beckwitt's screen name “3Alarmlampscooter” -- Khafra decided to pursue a business partnership with Beckwitt.

Beckwitt invested roughly $6,000 into Khafra’s start-up company Equity Shark, which according to his Linkedin page was “the future of private securities trading. In stealth mode.”

The two signed a written agreement before Khafra even got to work on the tunnels.

From there, Khafra began digging in the early months of 2017, according to Beckwitt. Aside from his work in the tunnels, Khafra also spent time in the bunker bringing his vision for Equity Shark to life.

Although Beckwitt painted the picture that the two were good friends. Khafra slept downstairs in the bunker inside the tunnels and was never actually allowed inside the home unless there was an "emergency."

Beckwitt told police he provided a mattress for Khafra to sleep on and stocked the bunker with food, water, sleeping bags and internet access.

“It was a pretty cool, chill spot,” Beckwitt told authorities.

Beckwitt said he would load items into a bucket and drop it down for Khafra when he needed and also provided a bucket for Khafra to relieve himself.

In Beckwitt’s eyes the agreement between the men was ideal -- he paid Khafra $150 a day in cash for the time he spent digging in the tunnels while also maintaining the level of secrecy he desired.

In fact, Beckwitt was so secretive about the tunnels that he told police he had rented a car to pick up Khafra in Silver Spring, Md. before driving him to Manassas, Va. Once they got to Virginia, Khafra was told to put on black-out sunglasses -- practically blindfolding him -- before he drove him back to Bethesda.

Instead of telling Khafra the truth, Beckwitt told him they were headed to an undisclosed location in Virginia.

Though Beckwitt tried to convince other people to agree to be blindfolded to work on the tunnels, they declined stating how they were uncomfortable with the process.

Beckwitt told investigators another man jokingly took the blindfold off after a full day of digging. Instead of laughing it off, Beckwitt said he told the man he would never be allowed back at his home because it would blow their cover.

Khafra, according to Beckwitt, didn’t seem to be bothered by the odd requests. Beckwitt said Khafra would stay in the bunker for several days at a time and would “dig until total exhaustion.” Beckwitt said Khafra had stayed a little more than a week around the time of his death.

It was later revealed that Khafra borrowed $3,000 from Beckwitt and was working to pay it off around the time of his death. A few more days of working would have brought his balance down to zero.

Investigators questioned Beckwitt about the level of secrecy around the tunnels including his motive for preventing Khafra from seeing. Beckwitt insists this was to prevent anyone from figuring out where the home actually was. Investigators pushed back saying if Khafra had internet access, he would have easily been able to find out where he was.

Beckwitt said this was impossible because he was using a forwarding server which directed web traffic to make it appear as if the home was in Virginia. It was then revealed that Khafra somehow found out where the home was and told his parents -- a revelation that left Beckwitt stunned.

Sept. 10, 2017

On the day of the fire, Khafra messaged Beckwitt telling him the lights were out all night the night before. Beckwitt told investigators Khafra was completely in the dark due to a problem with one of the extension cords that led to the bunker.

Khafra later messaged Beckwitt saying he saw smoke. Beckwitt claims the message came in while he was sleeping and did not raise alarm because Khafra later sent another chat saying nevermind.

Beckwitt said hours later he went down to test the extension cord, pulled it off and put a brand new one in. These cords were a part of the dangerous power strips prosecutors mentioned during the trial.

When asked about the cords, Beckwitt insisted he did not think the cords he tampered with had anything to do with the fire. He said there was no visible burning or smoke and reassures that Khafra would have been the only person to see anything if he was down in the tunnel.

Investigators asked why Beckwitt didn’t go down immediately when Khafra texted him, he responded that he was asleep and Khafra may have not wanted to bug him while he slept. However, court documents show Khafra calling and messaging him multiple times the night before.

Around 4 p.m. Beckwitt said he heard the carbon monoxide detector beeping while he was in bed on the second floor of his home. He claimed he did not get up because he thought it was the kitchen breaker, and just continued scrolling through the internet.

About 20-30 minutes later Beckwitt said he went down to check and reset the breaker in the basement when he saw smoke rising up through the kitchen floor. He then went back down to the basement to yell out to Askia who was down in the tunnel.

Beckwitt said all he heard back was “Yo Dude!” the last words he heard from the man he called a friend.

Beckwitt eventually ran outside where he saw neighbors congregating outside the home. Instead of waiting for fire officials to show up, Beckwitt said he ran into the home looking for his friend and also to remove gas cans and propane tanks away from the home.

He recalled not being able to see anything inside, as his eyes were watering from the billowing smoke.

WUSA9 previously reported Beckwitt’s home had “hoarding conditions" at the time of the fire - officials found things like human excrement, discarded items, saturated materials and piles of garbage in every inch of the home.

Yet despite the poor visibility and extreme hoarding conditions, Beckwitt said he believed Khafra should have been able to find his way out of the home either through the basement tunnel or a basement door he kept locked with the key still inside “in case of an emergency.”

Court documents revealed that there were other “emergencies” when Beckwitt had to leave his home to care for his father. Instead of leaving Khafra there, Beckwitt said he bllindfolded Khafra, took him to a friend’s house and then came back to get him later.

Though Beckwitt stood firm in his claims that he trusted Khafra, authorities debunked that claim by asking why did he blindfold him? They also questioned if Khafra actually knew how to get out, why didn’t he just go to the basement door. Why was he found in the laundry room? “Well that’s the $64,000 question isn’t it? Your guess is as good as mine” Beckwitt said.

“He certainly wasn’t blindfolded the whole time,” Beckwitt explains. “He knew his way around that basement.” -- this almost certainly places blame on Khafra for his own death rather than on Beckwitt.

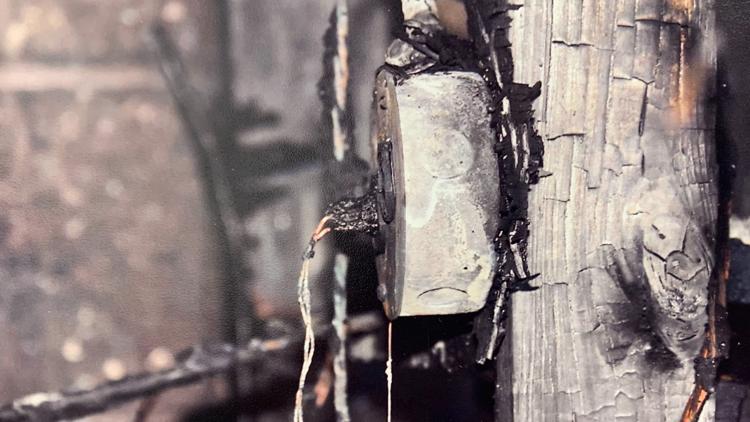

Damage after the fire on Danbury Road

The Trial

The saga continued through as the case moved to trial in April. Prosecutors said Beckwitt showed a "wanton disregard" for Khafra's life. When Khafra texted Beckwitt just before the fire broke out and said he smelled smoke and the lights went out, Beckwitt did not budge.

Montgomery County Assistant State's Attorney Doug Wink said Beckwitt just threw the switch on the fuse box and left him down there instead of looking for the cause of the fire.

Wink also said Beckwitt refused to let Khafra out of the 20-foot deep tunnel without black-out glasses. They alleged Khafra was led through the house with a string, and that when fire broke out, Khafra likely had no idea how to get out.

With hoarding conditions as bad as they were in Beckwitt’s home, escape through the maze-like pathways would have been extremely difficult, if not impossible.

"The substantial electrical needs of the underground tunnel complex were served by a haphazard daisy-chain of extension cords and plug extenders that created a substantial risk of fire," Montgomery County Detective Michelle Smith said in a court affidavit.

Beckwitt’s defense attorney Robert Bonsib fought back by painting his client as an “unusual individual” and insisted he was not a threat to the community. He said Beckwitt dug the tunnels out of pure fear of a North Korean nuclear attack.

The defense said Khafra was proud of his work digging the tunnels, judging by the photos he posted of himself in a mask and helmet while down in the tunnels.

Prosecutors said despite this, Beckwitt still knew the set up was a fire risk and did nothing to help Khafra when he received the text about the smoke.

But the defense argued Beckwitt did his best to rescue Khafra, even going back into the burning house to get him. Bonsib said Beckwitt inhaled so much smoke, he ended up in the hospital for four days.

Bonsib called Khafra's death "simply a tragic accident."

Despite the defense’s efforts, Beckwitt was found guilty of second-degree depraved heart murder and involuntary manslaughter on April 24.

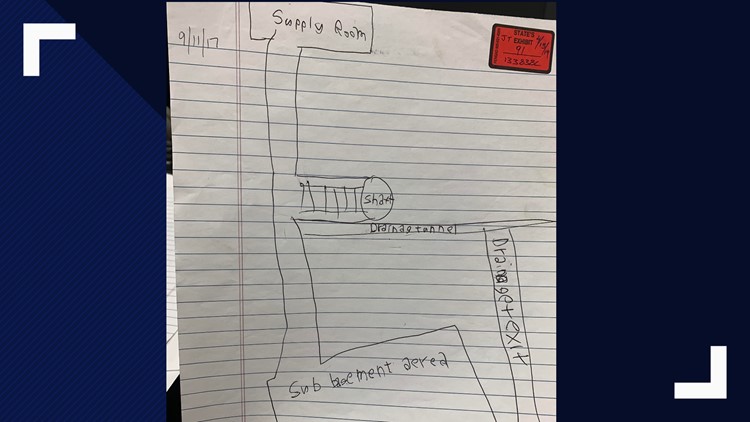

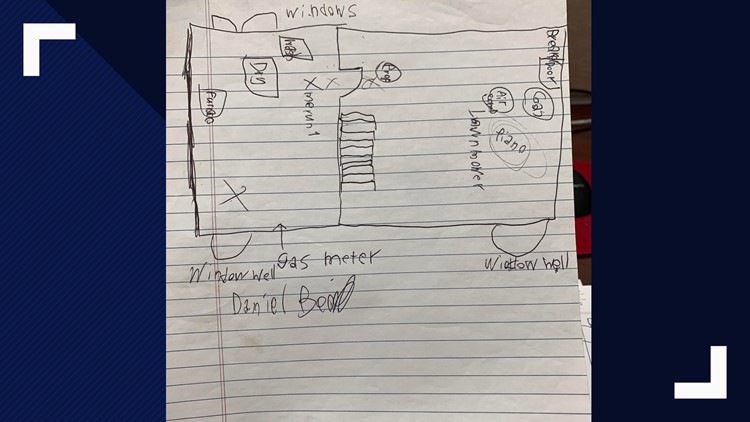

Photos of Beckwitt and sketches of tunnels

The Sentencing

On a warm and sunny day in June, people filed into a courtroom on the seventh floor of the Montgomery County Circuit court. Some pulled chairs behind them, as it was so crowded that there was standing room only.

As the courtroom stood for Judge Margaret Schweitzer’s entrance, moments later, Daniel Beckwitt entered the room. His hair had been freshly cut, it appeared, and slicked down with gel. He wore a green jumpsuit and though not visible, by the sound of it, had his feet in chains.

One by one, family members and friends spoke about how Beckwitt’s actions had robbed them of their loved one.

Askia Khafra’s father, Dia, went first, recounting the moments he’d first learned of his son’s death.

“It was Tuesday, September 12, 2017. An unremarkable day by any standard but one that has been etched indelibly into my psyche,” he said. “That was the day I responded to three police officers at my front door.”

He recalled hoping they were there for a case of mistaken identity.

“In impeccable English … I asked, ‘to what do I owe the pleasure of your visit?’” he said, inviting them in.

“Mr. Khafra, we have reason to believe your son was burned to death at a fire in a house in Bethesda,” he recounted the officers telling him. He said he sent up a silent prayer, still, that this was a case of mistaken identity. He said he recalled how his first wife died after giving birth to his older son in Trinidad.

“Here I am again, immersed in another surrealistic experience,” he said, sadly.

Beckwitt pursed his lips, and nodded as Dia Khafra spoke of his dead first wife and the moments he learned of his son’s death.

The elder Khafra said he began to cry and excused himself to the kitchen to compose myself.

“Typically, I would comfort myself with the oft-quoted remark, ‘this too shall pass,’” he explained. But all he could think of was “so this is how it had to end.”

The next months were filled with investigations and the trial, but Dia Khafra spoke about moments in time, when the loss of his son was most painful.

“People often tell us that they can’t imagine what we are going through,” he said. “They are infinitely correct. It is indescribable.”

Askia Khafra’s mother, Claudia, spoke next. Forcefully, she explained she will be forever traumatized by the loss of her only biological son.

“Words cannot explain the emotional trauma I experienced,” she said. “I go to sleep crying, I wake up crying.”

As she spoke, Beckwitt wiped his eyes with a tissue, and Dia Khafra stood to put his arm around her.

She remembered how she would often hear Askia shower in the early hours of the morning, and thank god for the “wonderful gift Askia was for me.” She said she lies awake at night now, during those same hours, but with a different prayer.

“My prayer is now asking God for the strength and the courage to continue living without Askia in our lives,” she said. “So far, this has proven to be an insurmountable task.”

She recalled one evening during the trial she walked out of her home in pouring rain, sobbing, and hoping she would be hit by a truck.

"Since his death, we have been traveling down very dark paths...there were moments I thought I didn't want to live anymore and I actually entertained thoughts of making it happen," she said. "Askia's death has left me broken."

More friends and family testified, and pointed out they had never received an apology from Beckwitt, just a condolence card.

At the end of the sentencing, Beckwitt stood to address the family and judge.

"I am sorry for what happened but sorry doesn't even begin to cover the magnitude of the tragedy," he said. "Sorry is what you say when you bump into someone with a cart at the grocery store."

"If there was something, anything, I could do to bring Askia back, anything, I would jump at the chance," he said. "But there is nothing that can be done at this time."

Beckwitt repeated that he tried to rescue Askia from the fire, and he didn't intend for any of this to happen.

"I will not beg for forgiveness, that is a decision you must deal with on your own," he said. "I just hope that over time you can come to terms with what happened and find peace."

The judge, after watching a slideshow of family photographs of Askia Khafra, said there was nothing they could do to bring justice to Khafra's family and no amount of years behind bars would bring him back.

"All these numbers trivialize the loss of life. Thirty, 20, 15, five ... even life without parole, they trivialize it," she said. "My sentence will not and cannot give you justice. It just can't and it won't."

She then gave Beckwitt 21 years, with all but nine suspended for the death of Askia Khafra, plus five years of supervised probation. That means he will serve nine years, then five additional years on probation.

"It is my opinion that you have what we call intellectual arrogance. You thought that everything would be fine because you were really smart," Schweitzer said. "And you didn't perceive what most of us would consider to be really dangerous."

The judge also issued a no contact order for Beckwitt with the Khafra family.

She said she hoped Beckwitt will use his intelligence for good in the future.

“It is a waste of your talents - I can’t imagine what you could’ve done if you’d considered altruistic needs,” she said. “So it’s my hope that you find a way to use your talents to better our community and have a little bit of that dreamer Askia Khafra in you.”

The defendant's counsel said during the hearing they plan to appeal the judge's decision.