WASHINGTON — This story was originally published on June 6, 2020.

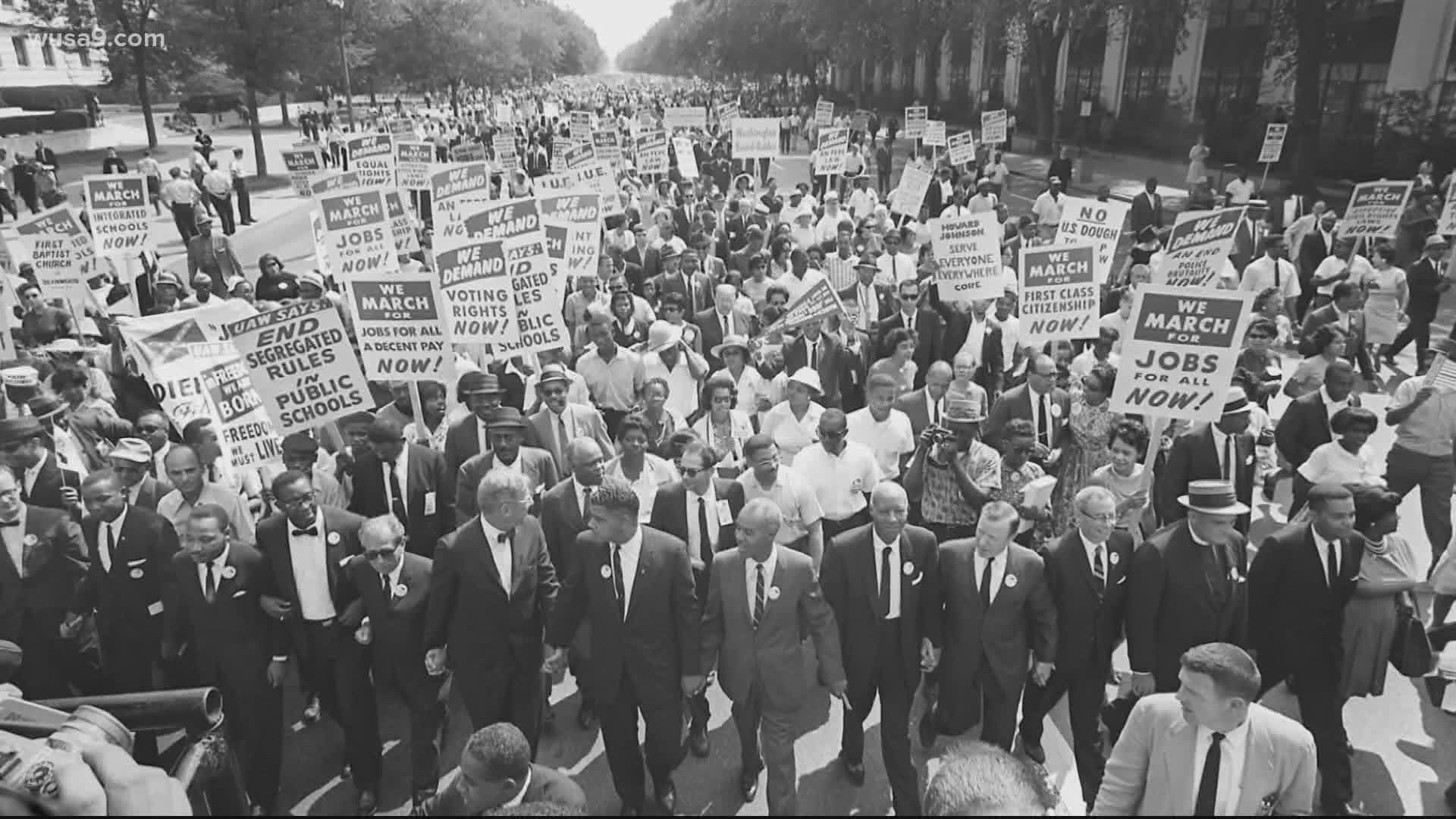

It was no accident protesters took to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial on Saturday to call for systemic change in response to the death of George Floyd. From singer Marian Andersen, to Congressman John Lewis and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the monument has been a beacon for generations of civil rights leaders calling for change.

Lawmakers and D.C. residents, and millions of others across the country, have been shocked this week by images of military personnel blocking all 58 steps of the Lincoln Memorial during ongoing protests in the nation’s capital. It’s an image that seems antithetical to the words delivered by President Abraham Lincoln during his second inaugural address: “With malice towards none. With charity for all.”

This temple, as the inscription reads above Lincoln’s head, is meant to enshrine the memory of America’s 16th president – the president who led the country through the Civil War and issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Since it first opened in 1922, that memory has drawn civil rights champions to its steps.

On Easter Sunday 1939, singer Marian Anderson, a black woman, took to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to sing “America (My Country, ‘Tis of Thee)” to an audience of more than 75,000 people after the Daughters of the Revolution denied her the chance to perform at Constitution Hall because of the color of her skin.

Two years later, as the nation prepared for World War II, A. Philip Randolph, the president of the Sleeping Car Porters, called for the end of discrimination in government and the defense industry. He worked to organize and mobilize mass protests, including a march on Washington to take place on July 1st.

Six days before the demonstration – in which Randolph promised to bring 50,000 blacks to march on Washington – President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed the Fair Employment Act that prohibited ethnic or racial discrimination in the nation’s defense industry and established the Fair Employment Practice Committee.

The Lincoln Memorial is where civil rights leaders went to demonstrate the lack of desegregation in schools. It’s where a 23-year-old John Lewis – decades from being called Congressman John Lewis – stood on the steps to deliver a message nearly identical to the ones protesters are crying out today.

“We are tired of being beaten by policemen,” Lewis said. “We are tired of seeing our people locked up in jail over and over again. And then you holler, be patient.”

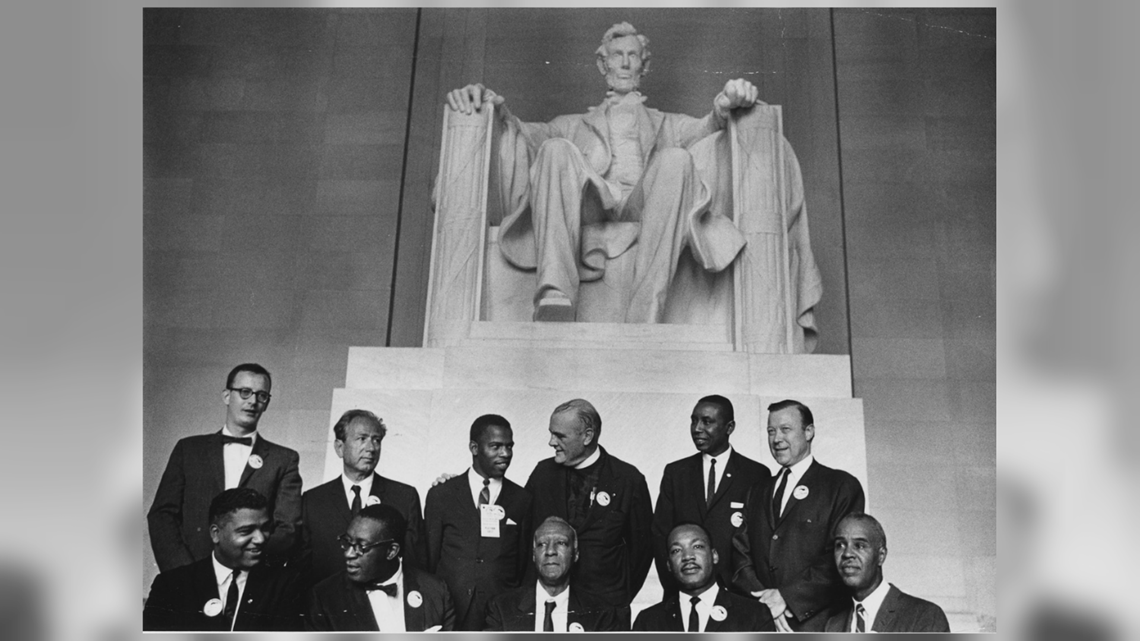

The Lincoln Memorial is where, on August 28, 1963, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stood and told the nation about his dream of racial equality.

“We’ve come to cash this check,” King said. “A check that will give us the riches of freedom and the security of justice.”

On Saturday, demonstrator after demonstrator echoed Kings' and Lewis' cries for justice and reform.

“My job on the regular, every day is to encourage people. How can I encourage people when I don’t believe in the system that is killing us? Literally killing us," one speaker said. "What we’re fighting for today… is anybody confused right now? We’re fighting for justice. Because we’re tired of just getting a charge and not a conviction."

For these demonstrators, like many Americans, the Lincoln Memorial is a place of reconciliation – the sacred ground where they can safely protest.

A sanctuary, of sorts, where they can go to help heal what’s ailing America and not fear armed soldiers standing shoulder to shoulder on the steps where history is made.