WASHINGTON — As measles outbreaks continue on both coasts, D.C. Health officials say they’re closely monitoring the District’s declining vaccination rate as they try to prevent it from becoming the next hot spot.

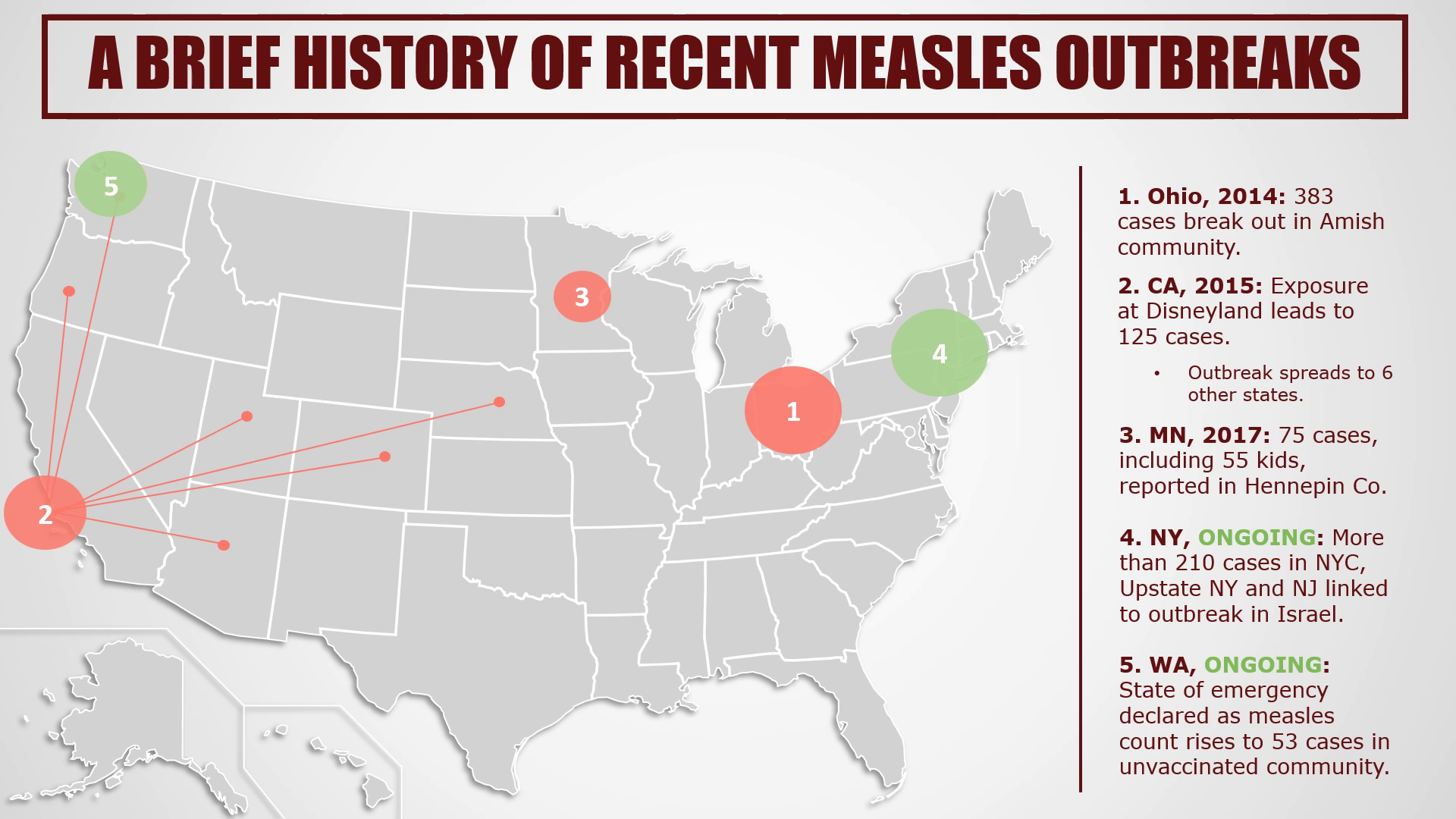

The state of Washington declared a public health emergency last month amid a growing number of measles cases in Clark County, which is located just north of Portland, Oregon. At the latest update, the outbreak had grown to 64 confirmed cases, including cases that had spread to Portland, Seattle and Hawaii.

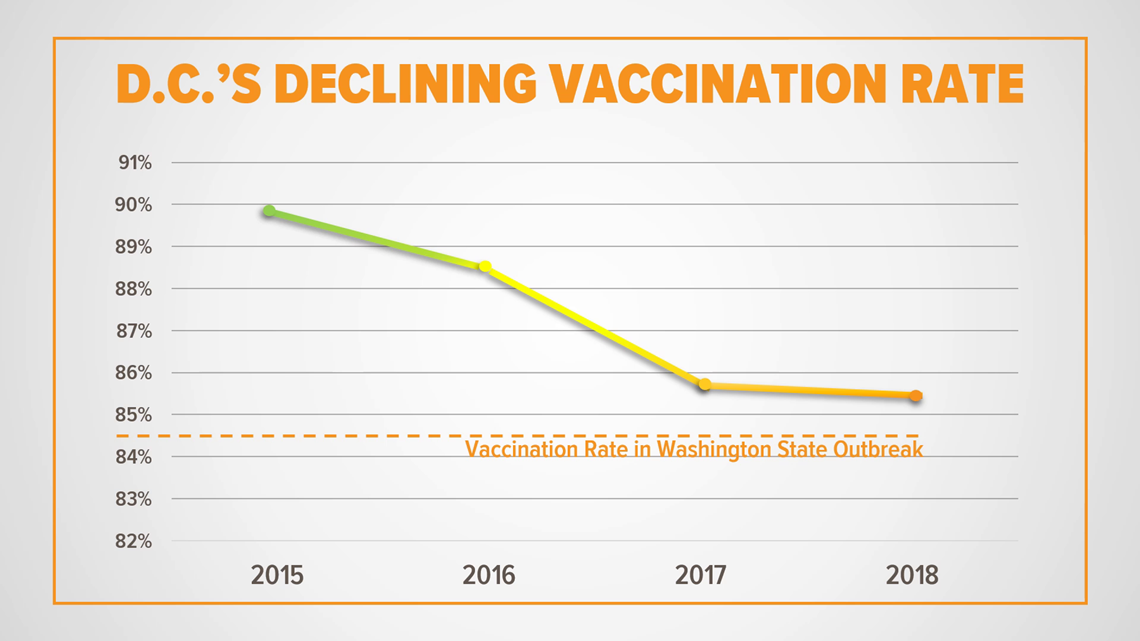

The MMR vaccination rate among kindergartners in Clark County has dropped to 84.5 percent, according to data from the Washington State Department of Health – fueled in part by sharp rise in vaccine exemptions. Nearly 8 percent of kindergartners in Clark County claimed vaccine exemptions during the 2017-2018 school year, and of those, nearly 80 percent were for non-medical, non-religious religious.

On the East Coast, more than 240 cases of measles have been confirmed among members of the Orthodox Jewish community in Brooklyn and Rockland County, New York, as well as Ocean County, New Jersey. Health officials believe the virus, which was declared eradicated in the U.S. in 2000, was brought to the states by travelers returning from Israel.

Israel’s Ministry of Health says more than 1,300 people have been infected in its current outbreak. At least one patient, a toddler, has died as a result of contracting the virus.

A Brief History of Post-Eradication U.S. Measles Outbreaks

The measles was declared eradicated in the U.S. in 2000 – but it can still be brought by back international travelers.

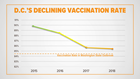

All of that has public health officials across the country on edge. In D.C., vaccination rates have followed the downward trend most of the rest of the country has seen. In 2017, only 85.6 percent of D.C. kindergartners had received both doses of the measles vaccine. That’s down from 89.9 percent two years earlier – and just one percentage point away from the rate in Clark County, Washington.

DC Health officials say that’s troubling, but note that the District has only had one case of measles during each of the past two years.

It was a stroke of luck, though, that the 2017 case didn’t erupt into something more serious.

An Outbreak Near-Miss

On May 13, 2017, a young boy hopped off a bus outside of Children’s National. His doctors had called ahead, seeking to admit him for flu-like symptoms. Physicians at the hospital agreed, and ordered him to be directly admitted.

He walked past the registration desk and was escorted up the elevator to a floor full of patients – where a doctor identified a serious problem: the boy had measles.

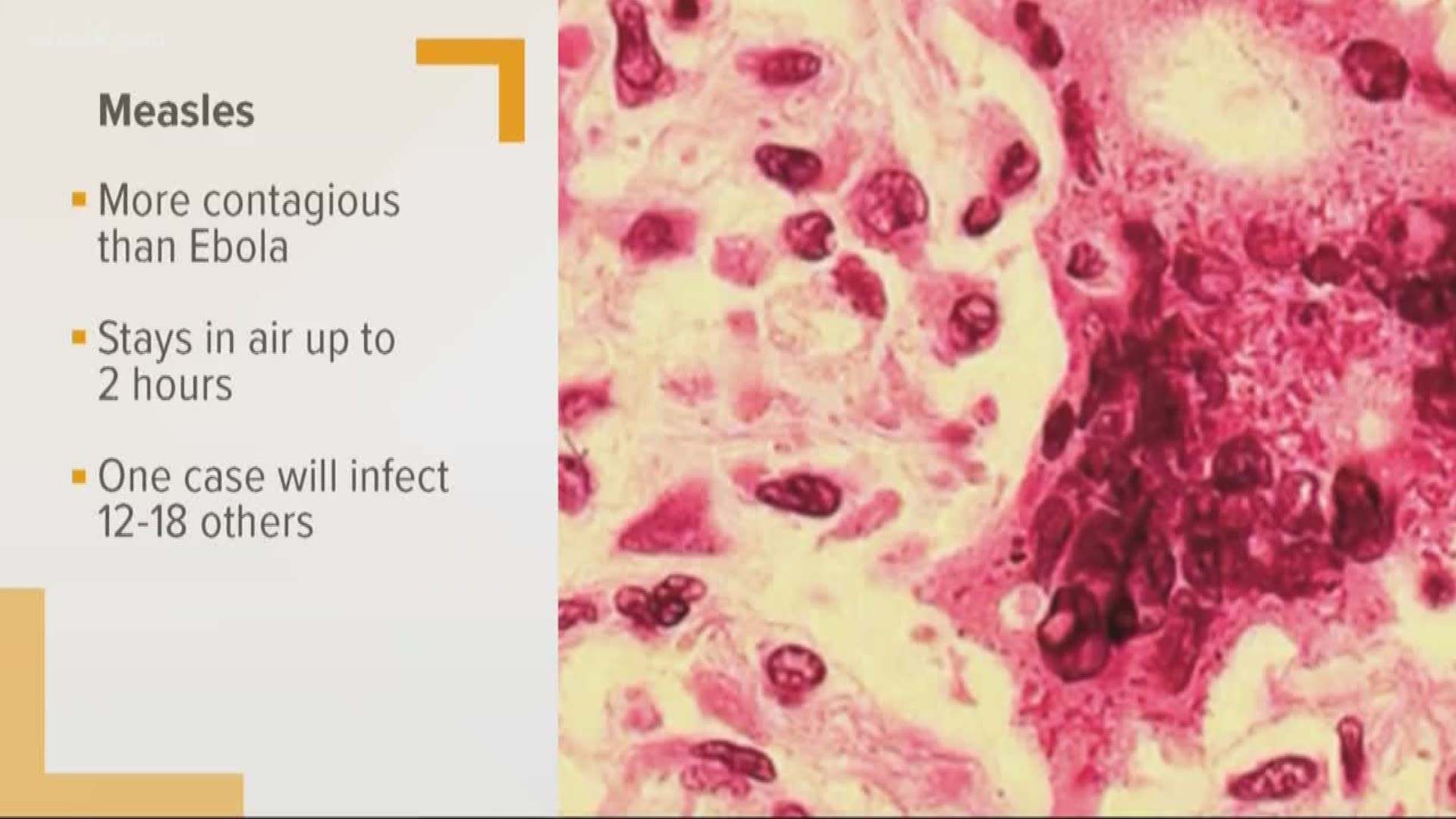

Measles is a highly contagious virus that attacks the respiratory system. It is often identified by the characteristic red rash that accompanies it, but carries with it more serious complications, including pneumonia, encephalitis – or swelling of the brain – and hearing loss. The CDC estimates 1 in 1,000 measles cases will develop acute encephalitis, which can result in permanent brain damage.

Out of every 1,000 children who contract the virus, one or two will die.

The boy was immediately placed into isolation, and Children’s Health infection control began scrambling to identify any patients he may possibly have come into contact with. Outside of the hospital, District health officials determined there may have been additional exposures going back five days prior at the Department of Social Services Building, the Social Security Administration Building and Prince George’s Hospital, along with the public bus the boy had taken there.

Amazingly, despite potentially hundreds of people who were exposed to the virus, no additional measles infection was ever linked to that case.

“We dodged a bullet there,” said Dr. Bud Wiedermann, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s National.

A Matter of When, Not If

Dr. Wiedermann has been treating sick children for more than 34 years. In the 80s and early 90s when he was just starting out in the profession, that often meant treating measles patients. But widespread adoption of the vaccine eventually dwindled those cases down to nearly nothing by 2000 – when the virus was declared eradicated in the U.S.

“Nowadays people in medical school, young physicians out of training, mostly have never seen a case of measles,” Wiedermann said. “They’ve read about it in books, but as you can imagine, it can be hard to diagnose if you don’t have the experience. It’s the somewhat oldtimers like me who need to help out younger physicians in how to recognize this from all the other viruses that cause fever and rash.”

Before the measles vaccine was introduced in the U.S. in 1963, the CDC estimates the virus would infect as many as 3-4 million people a year. Nearly 500 deaths annually were attributed to the disease – almost all of them children. Patients who survived could face deafness, permanent brain damage and lingering damage to their ability to fight off other infections.

But that was more than 50 years ago. While worldwide measles still kills nearly 100,000 children annually, the last measles-related death in the U.S. was reported in 2015. Wiedermann thinks the lack of personal experience with the virus is a contributing factor to the declining number of people who choose to vaccinate their children for it.

“It’s more than frustrating. I can’t begin to tell you. It’s just a very sad situation,” Wiedermann said. “I mean, we’ve got outbreaks in countries you wouldn’t normally associate with high rates of infections like England, France, Italy and Israel.”

A growing anti-vaccination movement that has spread online has also contributed to dropping vaccination rates. Health officials have linked the Clark County, Washington, outbreak to high numbers of parents in the area who’ve chosen not to vaccinate their children. Those same officials say they’ve seen a dramatic increase in the number of vaccinations given out following the outbreak. The New York State Health Department says in Rockland and Orange counties alone they’ve seen nearly five times as many vaccinations as previous years.

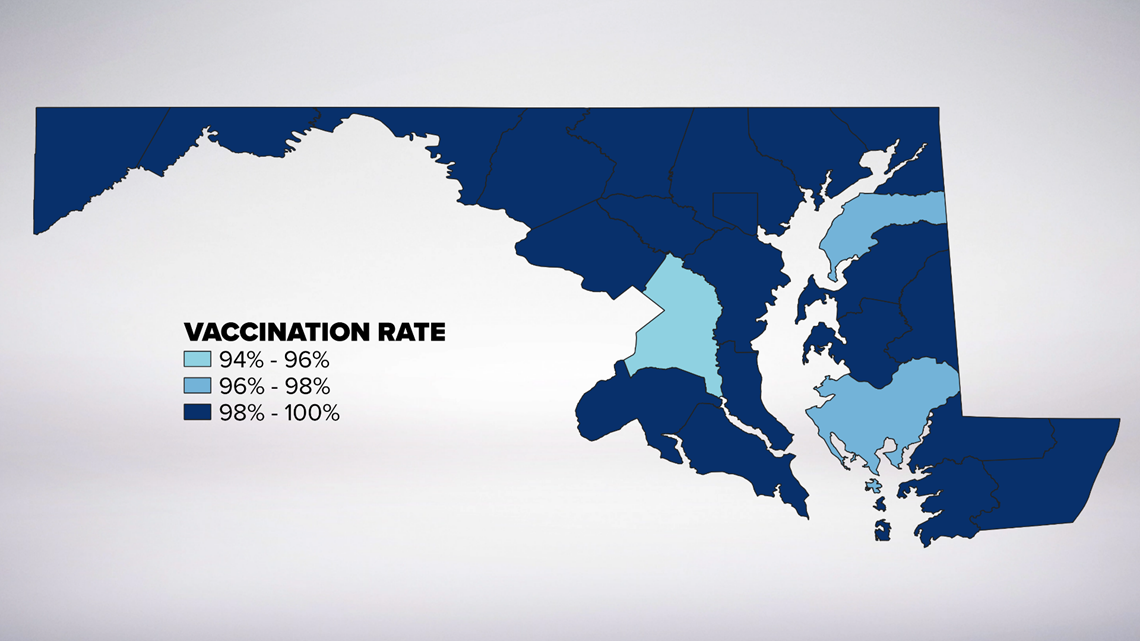

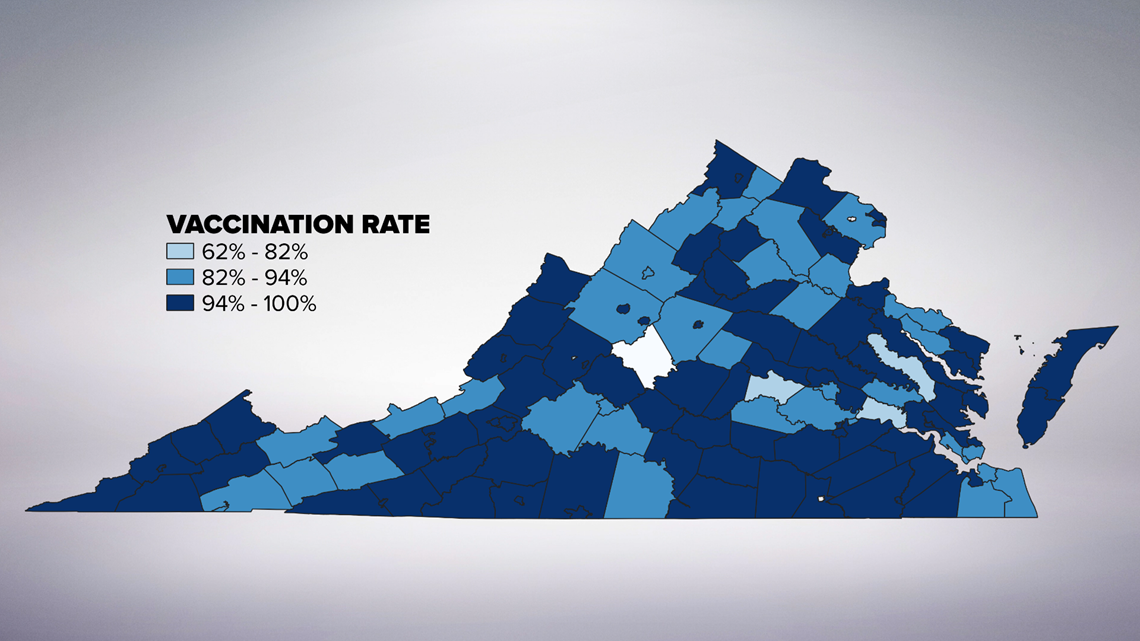

Unlike Washington state, neither the District nor Maryland or Virginia allow parents to claim philosophical exemptions for the mandatory vaccines children must get to attend school. Kindergartners in all three DMV jurisdictions have held a steady vaccine exemption rate of about 1 percent for the past several years. And vaccination compliance in the region generally is high.

According to the CDC, Maryland reported 98.6 percent of its kindergartners were in compliance for the MMR vaccine in fall 2018. Virginia reported 95.5 percent of kindergartners were vaccine compliant.

What remains troubling to Wiederman, though, is dropping vaccination rates across the board in the District. MMR compliance among D.C. kindergartners has dropped 4 percentage points in the past three years. Compliance with DTaP, which protects against diphtheria, tetanus and whooping cough (pertussis), is down 7 percentage points. Polio vaccine compliance is down too, falling from 92.2 percent in 2014 to 86.9 percent in 2017.

“Measles is about the most contagious, the most easily spread, infection we know of in man,” Wiedermann said. “Couple that with the declining immunization rate… unless something changes here, it’s more when is the outbreak going to occur in our area, rather than if.”

On the Front Line

D.C. has all the ingredients for an outbreak: declining immunization rates; high population density; a large airport; and lots of international travelers. But, DC Health says, none of that’s new.

The agency tasked with overseeing public health broadly, and vaccination compliance specifically, in the District isn’t ringing the alarm bells yet. For one thing, agency officials say, while the MMR compliance rate among kindergartners has been falling, the rate of kids who’ve gotten at least one dose of the vaccine – which is about 93 percent effective – has held around 94 percent for the past several years. And by the time kids get to 5th and 6th grade, they’re usually in compliance with all of their immunizations.

Part of DC Health’s mission is educating the public about the importance of vaccines – not just countering misinformation, but also filling in gaps in knowledge. For example, what makes the measles such a particular point of concern.

“People think of a fever, they think of a rash… [but] it can also have very severe consequences,” Talwalkar said. “It’s a highly, highly infectious disease. If you aren’t vaccinated you can enter a room two hours after a person with measles has been in there and still get the disease.”

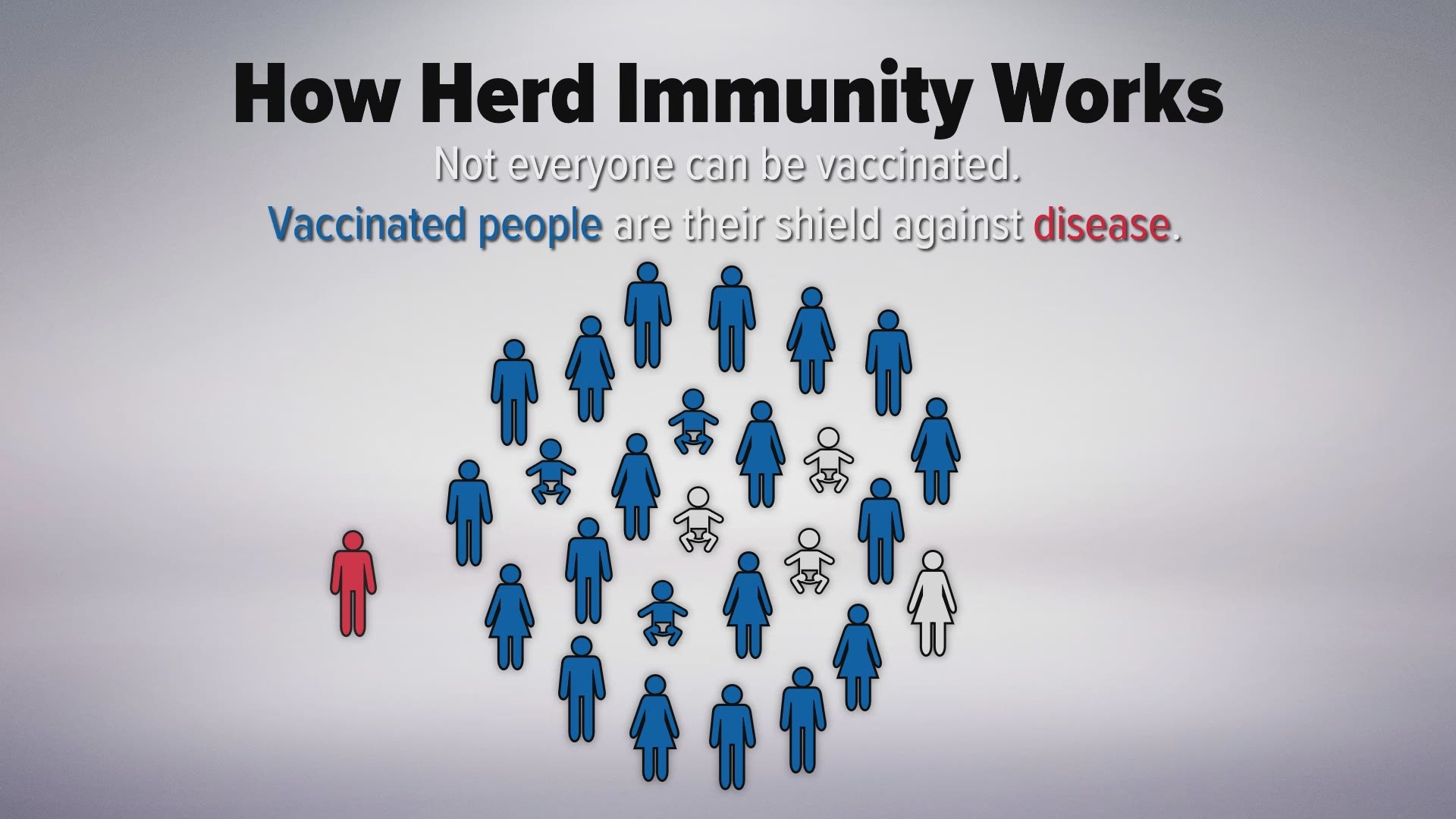

While the goal is to get everyone vaccinated who can be, a critical milestone is achieving herd immunity. That happens when roughly 95 percent of a population is immunized against a disease. Herd immunity is what protects people with weak immune systems and those who can’t be vaccinated – like infants, people undergoing chemotherapy and organ transplant patients.

How Herd Immunity Works

People who can't be vaccinated rely on herd immunity to keep them safe from vaccine-preventable diseases.

As of three weeks ago, Joel and Katie Simmons’ 5-month-old daughter Simone is in the latter category. Around Thanksgiving, Simone stopped eating and began breathing rapidly. She wound up at Children’s National, where she was diagnosed with dilated cardiomyopathy. The condition meant her heart had become dangerously enlarged trying to compensate for the left side, which wasn’t pumping blood. Doctors determined Simone needed a heart transplant.

Three weeks ago she got her new heart, and in just another week she could be going home. But, because she’ll be on immunosuppressants for the rest of her life to prevent organ rejection, Simone will never be able to get vaccines that use a live virus – like the MMR vaccine.

“I mean she’s even susceptible to the everyday cold, and our 5-year-old brings that home all the time. That itself could land her in the hospital,” Katie Simmons said. “So the measles would be devastating for her.”

Simone’s twin sister Naomi will be vaccinated as soon as she’s old enough (you can get the first dose of the MMR around 12 months). When they take her to get her shot, the Simmonses will be thinking a lot more about measles than when they took older sister, 5-year-old Vivian.

“It’s frightening, and that really limits what we can do, how comfortable we are with letting her go out, because we can’t protect her any other way but to have other people vaccinated,” Simmons said. “I mean the temptation for us is to put her in a bubble when we get home, and that’s not what we want for her. We want her to be able to go out into the world and have these experiences that other kids get to have.”

----

Jordan Fischer is a digital investigative reporter with WUSA9. Email him at jfischer@wusa9.com or follow him on Twitter @JordanOnRecord.