WASHINGTON -- For many young people, gay pride parades may seem like nothing more than a party. The parade route is full of music and color. There's clapping and dancing. The rainbow flag is everywhere.

But there's a lot more to the story.

The reality is that these parades started amid oppression and heartbreak. While it was a celebration from the beginning, it was a celebration in the face of discrimination. It's a story we should all remember.

Before The Riot:

The 1950's and 1960's were not a welcoming time for those in the LGBT community. Gay people were generally considered perverts, and were often fired from their jobs and publicly ridiculed if "outed." The American Psychiatric Association listed homosexuality as a mental disorder, and the FBI would keep track of "known homosexuals."

Gay behavior was illegal in 49 states. Engaging in any sexual behavior with someone of the same sex could land you in jail. Laws were made that outlawed the wearing of clothes, resembling the opposite gender.

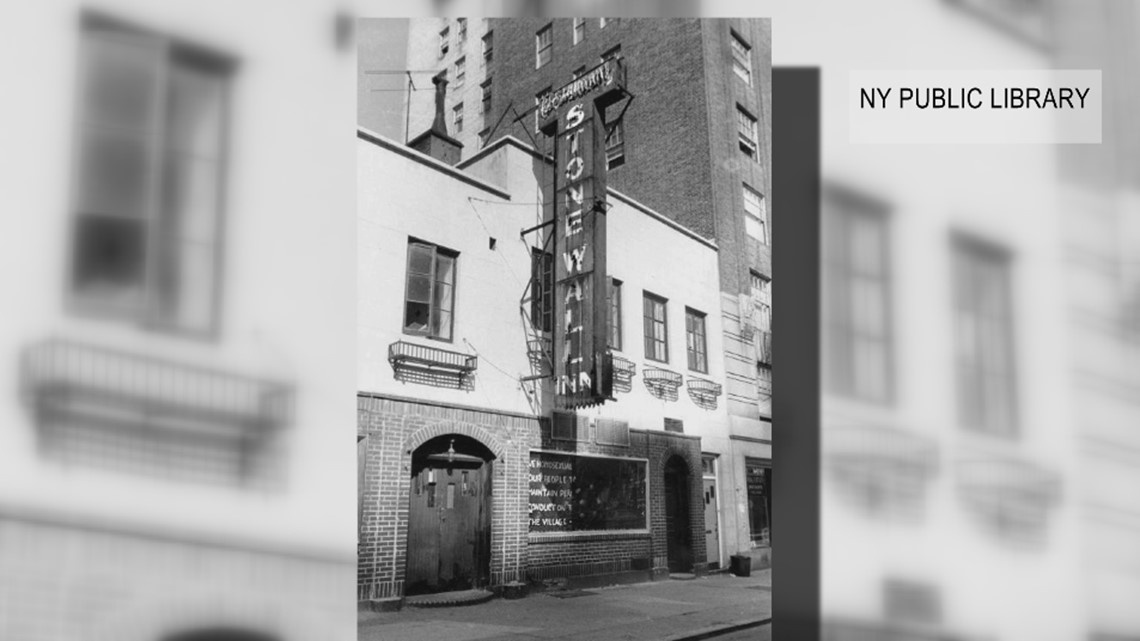

In New York City, as in many other cities, raids on gay bars were common. The State Liquor Association often would revoke liquor licenses for known gay bars, under the guise of breaking up "disorderly" hotspots.

One of those bars was the Stonewall Inn.

The Stonewall Riot:

While advocates had been fighting for LGBT rights throughout the preceding decades, many advocates believe the catalyst for the gay rights movement was the 1969 incident, known as the Stonewall Riot.

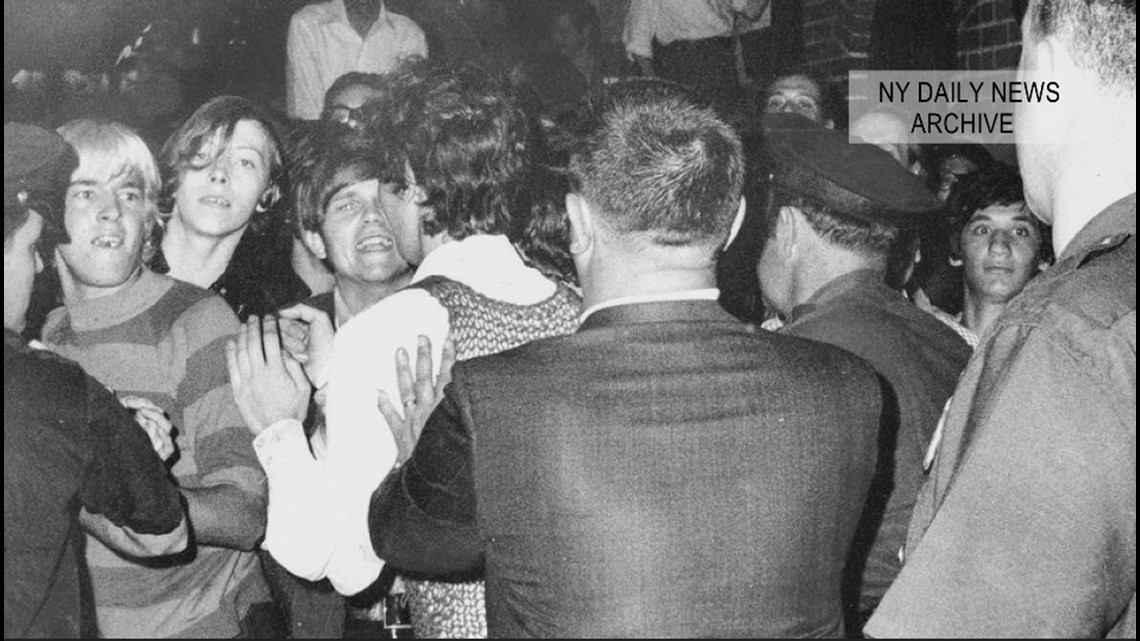

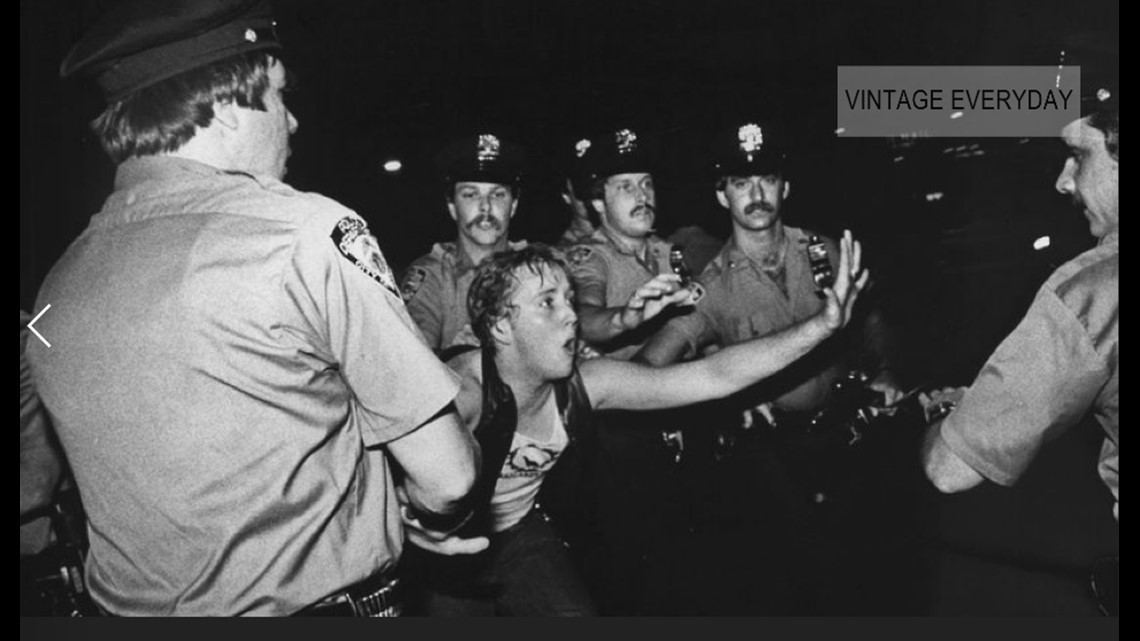

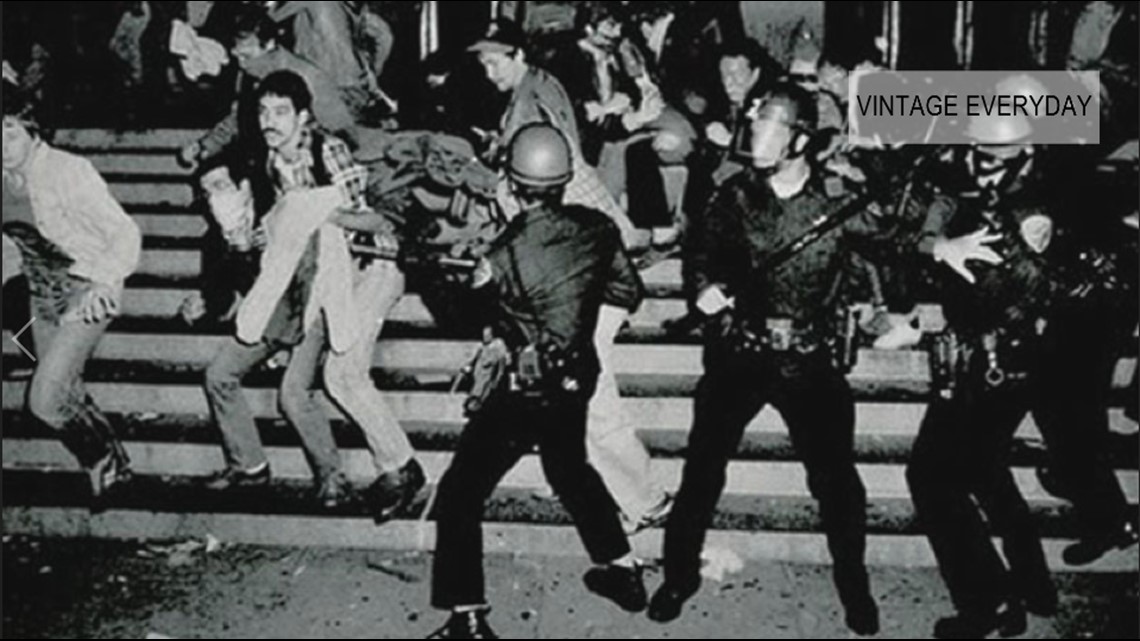

It all began at 1:20 a.m. on June 28, 1969. Police raided the Stonewall Inn, a popular gay club in Greenwich Village in New York City. Things escalated quickly. Police "roughed up" patrons, and arrested 13 people.

As was common at the time, female officers even took customers dressed in women's clothing to the bathroom to verify their sex. If they had male anatomy, they would be arrested.

Things then escalated. Many of those at the bar grew frustrated and hostile. Some started throwing things at police, and eventually the officers had to barricade themselves in the bar. The crowd even tried to set fire to the barricade. Protests and riots would continue for days.

The Years That Followed:

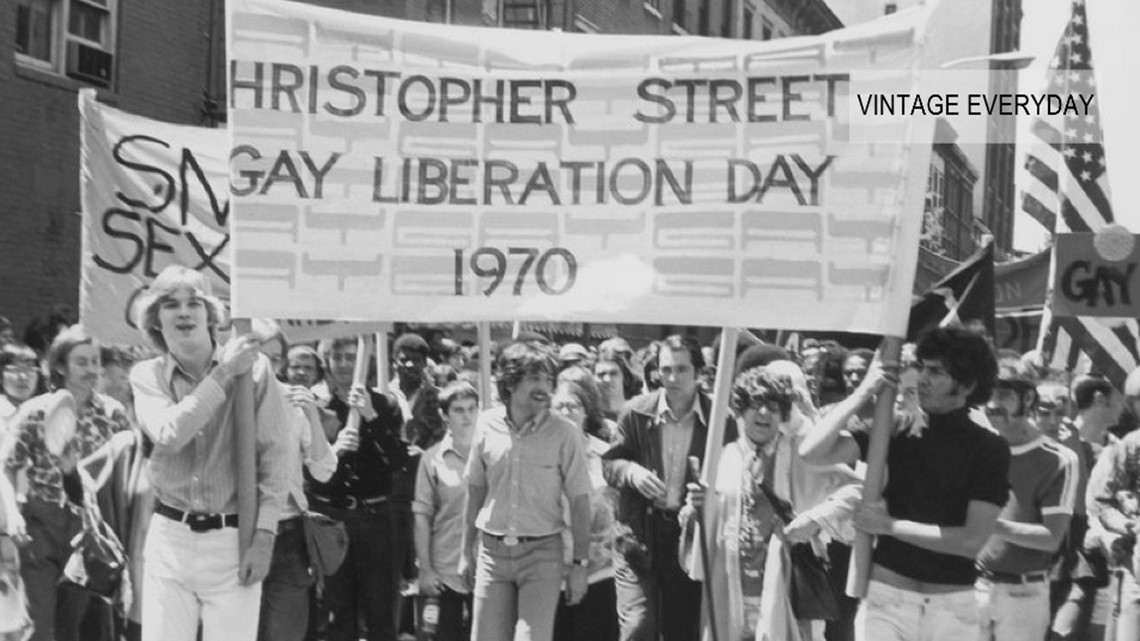

When the dust settled, activists decided an annual reminder was needed. In 1970, these activists planned the first ever "Christopher Street Liberation Day," named after the street where the Stonewall Inn was located.

That first year, there were also events in Los Angeles and Chicago. While these events were about protest and advocacy, they were also about celebration and pride.

By 1971, similar events had spread to places like Boston, Dallas, London, and West Berlin. In 1972, gay pride events came to Washington, D.C. Things really kicked off in the nation's capital in 1975.

Lambda Rising And The Birth of Capital Pride:

In D.C., the movement gained steam in the mid-1970's with the help of an up-and-coming bookstore called Lambda Rising. The store was founded by a man named Deacon Maccubbin. The store promoted LGBT literature, which was hard to find at the time, but it also acted as a safe haven for the gay community.

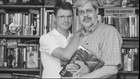

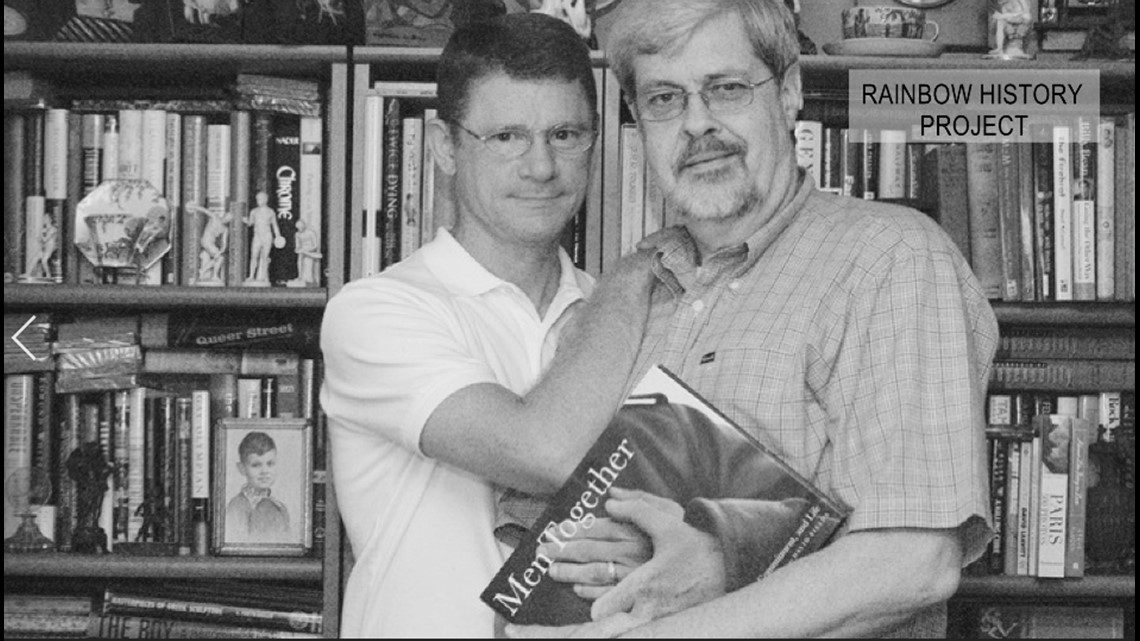

Maccubbin's longtime partner Jim Bennett met with WUSA9 to talk about that bookstore. The two have now been in a relationship for more than 40 years.

"In many degrees," he said. "It was a life-saver... We were hammered by religious people, by general ignorance, over and over and over again. And when you're beat up like that and you find something like this, it's a real treasure."

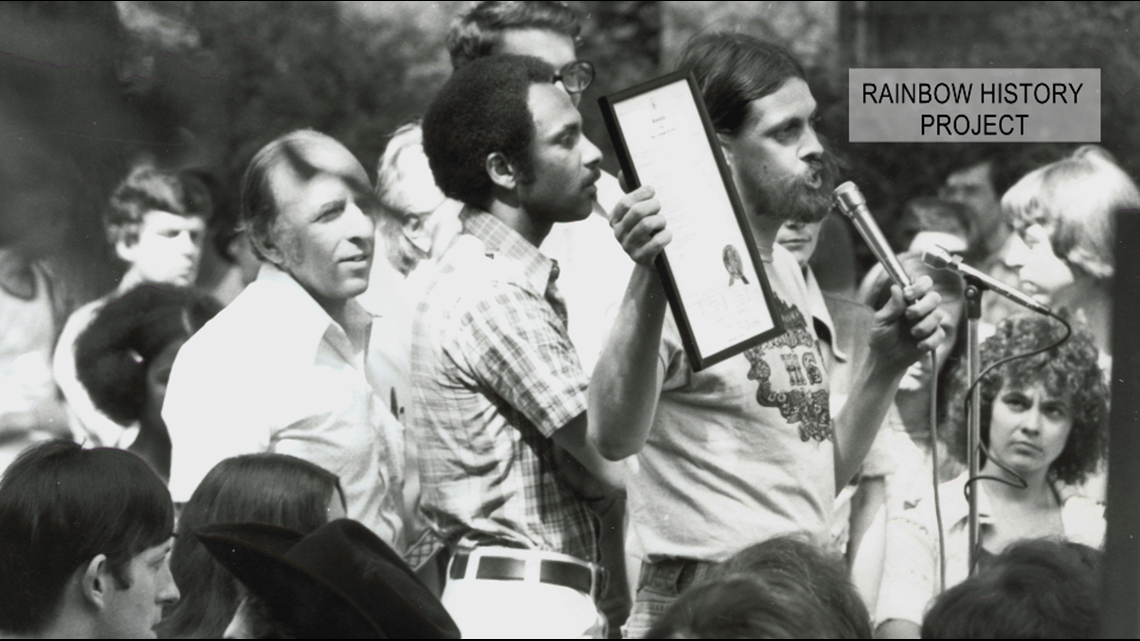

In 1975, Deacon decided that D.C. needed a formal gay pride event, like the one in New York City. He organized a one-day community block party, right by the book store on 20th Street, in Dupont. By 1979, some 10,000 people were flocking to Dupont for the event.

"It was amazing to see that many gay people," Bennett said. "Under the sky in broad daylight all proud and happy. And it was life-changing. It really was."

In the decades since this first event, there have been a lot of changes. The crowds have grown exponentially, and the level of acceptance has skyrocketed. It's ebbed and flowed between protest and celebration.

For Bennett, the parade of today is something they could only have imagined in 1969.

"We dedicated our lives to our bookstore," he said. "To our community. And I wouldn't change a thing... It meant something to the (community) where they weren't alone any longer."