WASHINGTON -- In Woodland Terrace, the sounds of children playing basketball and chimes from the ice cream truck gave Chauncey Anderson a little nostalgia.

"This is my hood," he said.

Anderson visited his old Southeast Washington neighborhood to catch up with old friends - those who remain.

He moved away recently to escape the violence.

"It wasn't too, too serious. Like, I ain’t never get shot," Anderson said. "I got shot at plenty of times, but, luckily I never got hit."

Anderson said the neighborhood was so dangerous, he felt the need to carry a gun, even as a teenager. The gun was to protect himself and friends in the neighborhood.

“It’s stupid. It’s just stupid. Dudes have issues over the smallest stuff like females. You might’ve stepped on my shoes or something, looked at me the wrong way," Anderson said, talking about what triggers some neighborhood violence. "Like, my father could’ve just died. I might be going through something right now and you’re worried about how I’m looking at you."

He said even at school, you might run into people from different neighborhoods who had a problem with you.

"Something might go on. You going to fight at school, but after school, it might change," he said.

Anderson was arrested twice, first at 15-years-old, for carrying a firearm. That's when he realized it was time to drop his weapon and aim for better.

He had a son to raise and at the same time, many of his friends were being murdered.

"It's a lot of lives being lost over the smallest stuff. Like, I got friends on my arms that I ain’t going to never see again," Anderson said.

However, Anderson said he made one new friend at the right time.

Duane Cunningham was walking through his neighborhood and frequently checked to make sure he was staying out of trouble.

"It was nice to have someone to talk to," Anderson said.

Cunningham understood the streets. He went to prison at the age of 18 and spent a decade behind bars for smoking and selling crack throughout D.C. in the 80s.

Cunningham is now one of D.C.'s 26 Violence Interrupters. He's walking the streets in some of the toughest neighborhoods, trying to identify and stop conflict before it turns deadly.

"It's a lot of trauma that's going on in their head they don't talk about and they're so used to it. So, when they do get mad. It's like rage," Cunningham said.

So far in 2019, there have been 58 murders in The District, surpassing the murder rate at this time last year.

2018 was one of D.C.'s deadliest in a decade, with 160 people murdered.

"A lot of those people were from my neighborhood. One of them was my best friend," another Violence Interrupter said. Robert Butler works with the Safer Stronger DC Office of Neighborhood Safety and Engagement.

With an average salary of $45,000 a year, the agency is looking for people who are now positive influencers in their community.

Robert said, even with his history of using drugs, his neighborhood contacts and street knowledge, the job is still tough.

"Guys I've mentored: Some have been arrested. Some have been killed," he said, sadly.

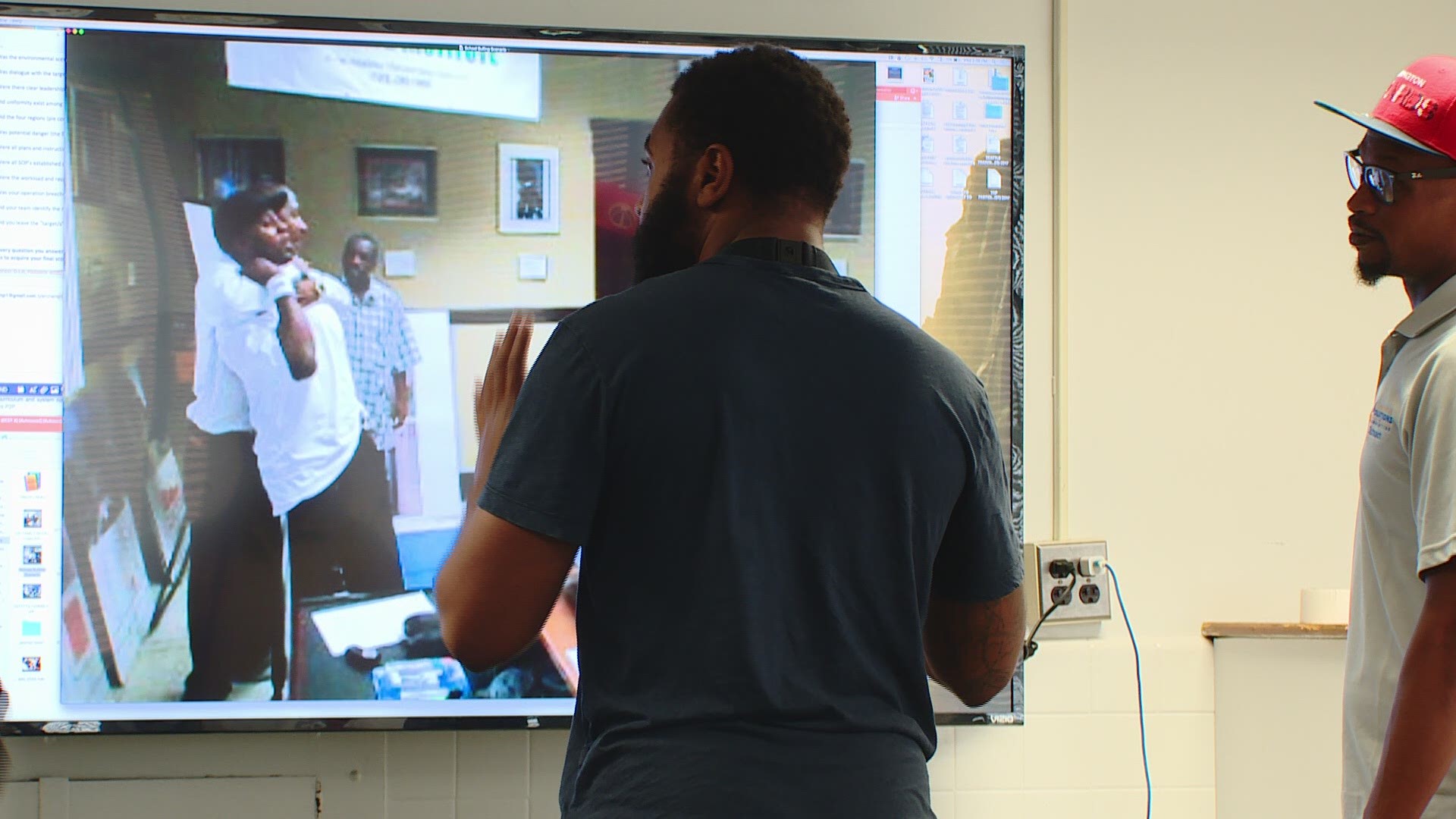

The team recently took part in a week-long training, conducted by a man known around the world for his violence intervention programs.

Aquil Basheer helped them with strategy, so they can effectively get through to people or groups on the verge of committing a crime.

Video below shows them reenacting a potential situation.

These violence interrupters say police aren’t trusted in many neighborhoods so they don’t work alongside officers.

Instead, they’re operating off referrals and information passed along by people who trust them in these communities.

Violence Interrupters are embedded in at least 20 neighborhoods throughout The District. They attend every community function and also host their own events.

India Blocker-Ford is a Violence Interrupter who spends weeknights working with young girls and boys, whether it's meditating to practice stillness or modeling to boost confidence.

“They've been going through a lot,” Blocker-Ford said. “The kids notice.”

A 6-year-old girl in her group was shot a few months ago. One boy's brother was killed, and another kid committed suicide.

“You hear. You hear all the violence going on. All the commotion,” one of her students said.

“I'm there for them. You know what I mean? I can be that shoulder for them to lean on and cry on,” Blocker-Fordsaid.

It’s tough to gauge how many murders these Violence Interrupters prevented in the first year of this program, but city data reveals, they’ve connected roughly 130 people to resources after tragic events, in some cases to prevent retaliation.

They’ve also successfully negotiated five cease-fires between feuding neighborhood groups.

One of their tactics include bringing in people they’ve helped, like Anderson, to show a life of crime isn’t the only option.

“Everybody gets into a little trouble. We used to beat people up for fun. Now that I’m older and I look back on it, that’s crazy. That’s wild. Wow. Why would we do that?" he explained. "But, when you in the hood and there ain’t that much to do, that’s what happens. You do stupid stuff like that."

There are plans to add additional Violence Interrupters this summer.

RELATED: Outrage in Southeast DC after video of man being shoved, arrested during confrontation goes viral