It has been a year since certified elevator inspector Audrick Payne went public. He blew the whistle on his employer, the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs.

He revealed a series of failures that put residents at risk every day: dangerous elevators, shoddy inspections, as well as "life and limb" hazards.

There are only three inspectors on staff to scrutinize more than 20,000 elevators in the city. That means each inspector would be responsible for more than 6,000 elevators a year.

Now, one year later, Payne says nothing has changed.

"There's no 'regulatory' going on. I call it the friends and family agency because 'regulatory' is out the door, big time," the elevator inspector said. "It's worse now than it ever was."

And, he's out the door, retiring from the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs (DCRA) with decades of experience in making sure your elevators don't become death traps.

Payne said the Macy's in downtown D.C. has been operating without a license for its elevators and escalators since 2015. According to court documents, in 2018 a Macy's customer received cuts, scrapes and bruises to their leg after being thrown from a malfunctioning escalator. Records detail that DCRA slapped Macy's with a $103,000 fine.

Three weeks after our deadline, we finally heard back from the retailer. In an email from Macy's spokesperson, Emily Goldberg, she said, that "all current operating equipment is up to date on inspections and certifications."

"It's all about accountability," Payne said.

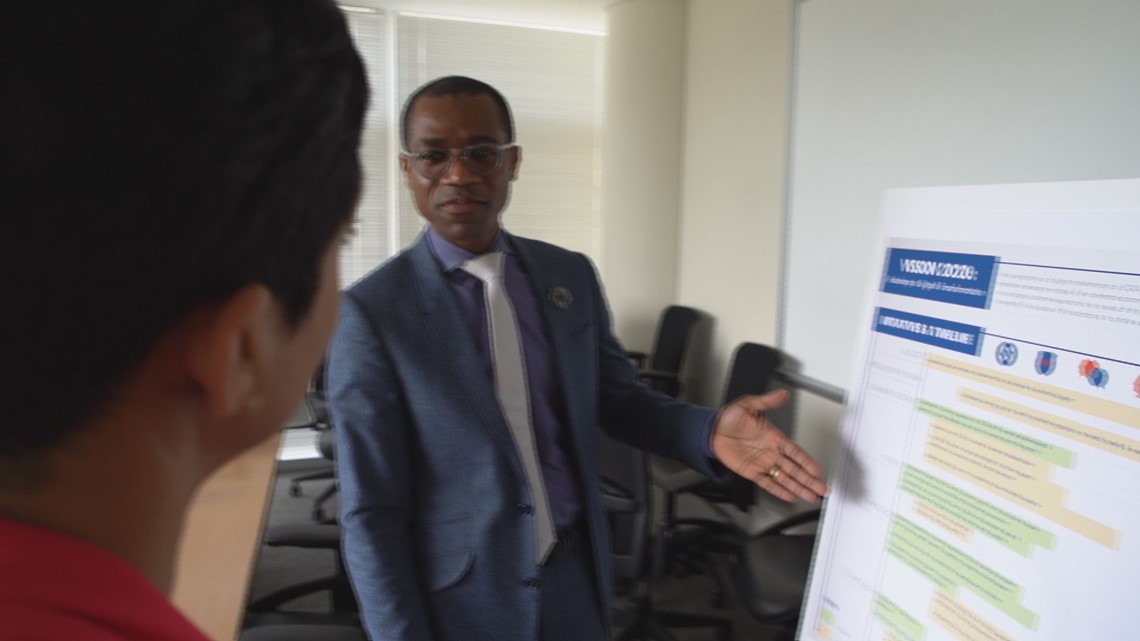

"To walk out the door and say 'I'm done.' I say 'no you're not done!'" Ernest Chrappah said. He recently took over DCRA. "We are rebuilding this. The 20 years you have, you just want to give up on that."

Chrappah doesn't want to see Inspector Payne go.

He admits DCRA has too few inspectors. So, he has a plan. For $250 and no more than a few months of training, D.C. residents can become a certified property maintenance inspector.

Right now, 68 inspectors crack down on illegal construction and make sure buildings are up to code.

Again, when it comes to elevators, there are just three inspectors on staff. DCRA depends on third-party inspectors to fill the gaps.

Where does that lead accountability when we know there have been third-party inspectors who have not done a good job?

When asked if adding more inspectors would make the city safer, Chrappah agreed.

"Adding more inspectors that you monitor in real time makes us safer," he replied.

Payne, meanwhile, wished Chrappah good luck in his efforts to rebuild DCRA.

"It's not going to take six weeks or three months," Payne said. "You better have some good experience or somebody's going to die trying to inspect something."

Payne has had to correct problems that a third-party inspector left behind. Elevators in apartment buildings, hotels and stores that were all tagged "life and limb hazards," but still allowed to stay in service.

"I don't have no favorites out here," Payne said. "I will write my mama a ticket if she violated! No one listens."

The elevator inspector has put his life on the line to keep people safe, blowing the whistle, hoping that someone would listen and fix the dysfunction at the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs that's putting people in danger.

But frustration is forcing him into early retirement, even though the acting director says change is coming.

"If we cannot get it done in a year in terms of turning it around, the customer expectations and delivering, then we're wasting our time," Chrappah said.

As for Audrick Payne, he's not convinced.

"I've seen this before," he said, disheartened.

D.C. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson still has his sights on breaking up the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs into two divisions. One for construction enforcement, the other one for licenses and consumer protection.