WASHINGTON — In the 25 years since it was founded, Amazon has grown into a household name, the most valuable publicly traded company in the world -- and the bane of affordable housing, according to its neighbors in Seattle.

Since 2000, average rent in Seattle has increased by more than 65 percent, according to the Seattle Times. Home prices have more than doubled over that period and continue to rise faster than anywhere else in the nation.

The result of a massive influx of high-wage tech workers and skyrocketing rents has been a transformation of Seattle, and a forced migration of low- and middle-income residents out of the city’s center and, in many cases, out of the city itself entirely.

"People are being priced out of very basic housing," said Sharon Lee, executive director of Seattle’s Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI). "We have so many people that have fallen into homelessness, or at the very edge of becoming homeless because of rent increases … they are literally being squeezed out of the home that they have lived in for 10-20 years. You could have multiple housing code violations and you could still not afford to live there."

The situation has grown so dire in Seattle that the City Council, spurred by a dramatic rise in homelessness in the city, voted to impose a payroll tax of $275 per employee for companies with revenues exceeding $20 million annually. A lobbying effort led by Amazon eventually resulted in a reversal of that vote.

How will Amazon change DC? We went to Seattle to find out

Amazon points out that it has invested $4 billion into its development of its Seattle headquarters. In 2020, the company will open a shelter for Mary’s Place -- a non-profit that helps women, children and families experiencing homelessness -- in one of its new Seattle buildings.

But for a company that reported more than $232 billion in revenue in 2018, housing advocates said it isn’t nearly enough.

"If we saw [Amazon was] responding with solutions around housing or solutions about unaffordability or homelessness or health care or education, that would be different," Lee said. "If they were doing too much, it would be fine to say you're doing too much. But nowhere are they anywhere near doing what they ought to be doing."

Walking into a crisis

In November, Amazon announced Crystal City, Virginia, would get half of the 50,000 jobs expected to be generated by its so-called HQ2 – now being split between the D.C. area and New York City.

Drawing Amazon to Northern Virginia cost the Commonwealth more than $1 billion in state incentives, including a direct $22,000 per year kickback for every job the company creates that pays more than $150,000.

Those jobs, and as many as 22,000 additional, indirect jobs Amazon’s presence might draw to the area, aren’t expected to have the oversized impact on rents in the D.C. metro they did in Seattle, though, largely because the D.C. area already has a housing crisis all its own.

The Washington-Arlington-Alexandria metropolitan statistical area, known by the shorthand "DMV," is one of the top 10 most expensive metros to live in the country. At minimum wage, the National Low-Income Housing Coalition estimates a person would have to work 91 hours a week just to afford a one-bedroom rental at the fair market rate. If D.C. were a state, it would be the second most expensive state to live in the country -- right behind Hawaii.

At the very lowest end of the housing spectrum, access to public housing has become nearly nonexistent. In most DMV jurisdictions, applicants can’t even get on the Section 8 waitlist. Arlington’s, which is closed indefinitely, has more than 5,000 names already on it and a five-year waiting period. Alexandria’s list, similarly closed, has 4,902 names and only turns over 242 families a year. Montgomery County, one of the few DMV areas where you can still get on the public housing wait list, estimates only around 8 percent of its wait list will have a unit become available annually.

Where is Housing Affordable in the DMV?

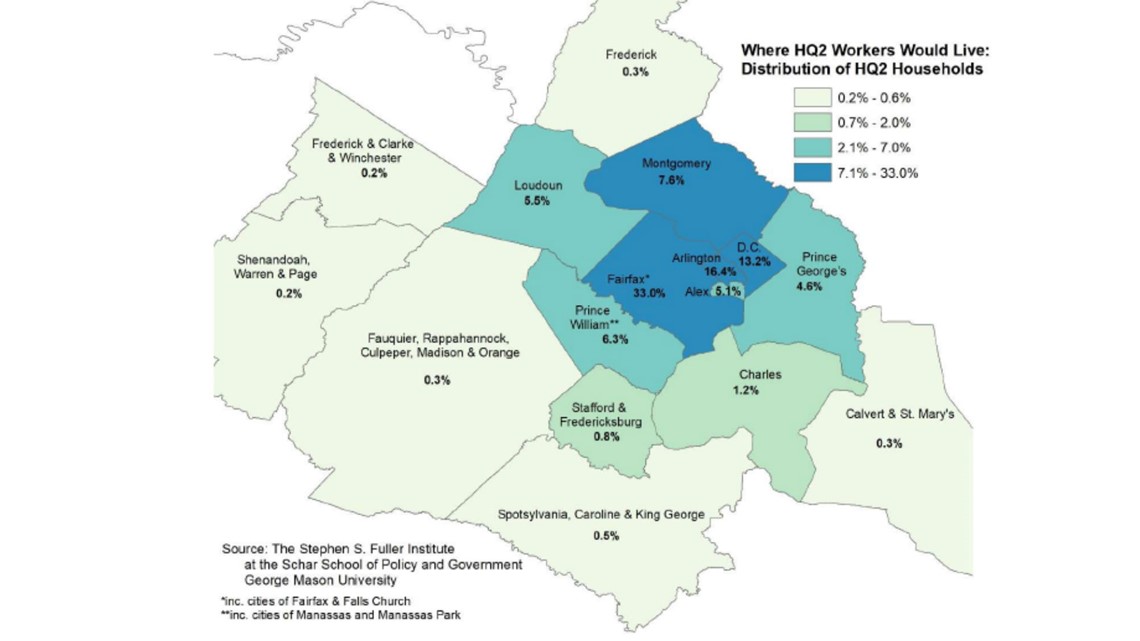

WUSA9 mapped out every unit of affordable housing we could find in the areas the Fuller Institute predicts will get the most new households from HQ2.

Data for this map was pulled from local government websites and publications and a national database of affordable housing. If you think your property has been missed, email jfischer@wusa9.com.

The picture is the same, although perhaps less immediately dire, for renters who fall above the poverty line but below the DMV’s area median income:

- The City of Fairfax said the price of housing in the city has "significantly outpaced wage growth." Exacerbating the problem, almost all new housing construction in the city over the past 30 years has been in the upper housing price ranges.

- In Alexandria, the city currently has an inventory of just 4,011 committed affordable units for the 18,280 families who make less than or equal to 80 percent of area median income.

- In Arlington, where Amazon will make its new home, the number of market-owned affordable units has been decimated, dropping from 20,000 units in 2000 to less than 2,500 in 2017. At the same time, the county predicts half of its current and future housing need will be comprised of households with incomes below 30 percent of area median income.

Jurisdictions around the DMV are dealing with the crisis in different ways. Over the past several years, the District of Columbia has allocated tens of millions of dollars annually to the preservation of the city’s existing affordable housing stock. Earlier this year, the city issued its first round of Preservation Fund dollars to help tenants at 11 apartments purchase their buildings through the city’s Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA).

Montgomery County has for decades had a law on the books requiring new housing developments with 20 or more units to dedicate between 12.5 to 15 percent of those units as affordable. The county beefed up that requirement in October by making it a mandatory 15 percent in areas where the median household income is at least 150 percent of the county median.

In Fairfax County, which a study by George Mason University’s Stephen S. Fuller Institute estimates could get as much as 33 percent of new households generated by Amazon, rising rents have spurred the creation of the Fairfax County Magnet Housing Program to help school teachers, police officers, firefighters and health care workers afford to live in the county where they work.

Fear across the river

Just across Four Mile Run, the residents of the Arlandria-Chirlagua Housing Cooperative have a clear view of Amazon’s new home in Crystal City. And what they see worries them.

Almost as old as Amazon itself, the Chirilagua co-op -- named after a town in El Salvador -- was founded in 1995 by a group of tenants after a decade of fighting against illegal evictions. The complex is comprised of 282 units occupied mostly by low-income, Spanish-speaking residents like Suyapa Gomez.

Gomez left Honduras 18 years ago. She found it in Alexandria, where she got married and now raises her three sons. Gomez said having a place like Chirilagua -- surrounded by the food, the culture and the language of her home country -- is a blessing.

Now Gomez and other residents of Chirilagua are worried that blessing may be threatened by Amazon and the inflated rents its highly paid employees promise to bring. She has been attending meetings at Tenants and Workers United, an affordable housing advocacy group which helped found Chirilagua years ago. She said her oldest son is starting to ask about the meetings, and to worry about what Amazon means to him.

"He asks me, 'If Amazon comes, are we leaving?'" Gomez said.

The Commonwealth of Virginia has already allocated $225 million to address the affordable housing crisis in the state. That translates to about $5 million annually for Alexandria, which comes out to roughly 200 new units of affordable housing a year -- a far cry from the 3,452 new households the Fuller Institute estimates may be Alexandria’s share of the Amazon bump.

Alexandria housing director Helen McIlvaine said the city also has plans to revitalize Mt. Vernon Avenue in Chirilagua, and to conduct a housing impact study later this year.

For Margarita Damian, one of Gomez' neighbors at Chirilagua, it’s not enough. And she worries that her home could be at risk if her neighbors, enticed by developers and their big wallets, vote to sell the property.

"I think it's empty promises" Damian said. "We want to tell them we’re here. We exist."

READ OUR FULL AMAZON COVERAGE