It’s not often that a museum exhibit can change a man’s life forever.

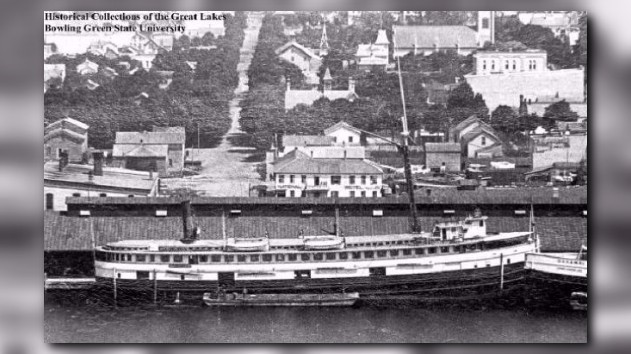

That exhibit is in the building known as “The Pump House.” You can’t miss it if you drive along Ottawa Beach Road in Holland on your way to Holland State Park. It’s an icon from a bygone era.

The Pump House is the last standing structure of the historic Ottawa Beach Hotel that was built in 1901, then burned down in 1923.

It sat dormant along the shoreline of Lake Macatawa for nearly 30 years, but within the past year, Ottawa County and the nonprofit historic Ottawa Beach Society have combined efforts to preserve and utilize the building in a way that will benefit the public.

The plan is to turn it into The Pump House Museum and Learning Center to feature exhibits, activities, and educational programs to stimulate and challenge the imagination by sharing history, memories, and stories that have made the area special for more than a century.

To give the public a taste of things to come, the Society asked Valerie van Heest, a board director with the Michigan Shipwreck Research Association, author, museum designer, and Holland resident, to design an exhibit about the story of the sinking of the SS Michigan as told in her book “Lost & Found – Legendary Lake Michigan Shipwrecks." It details the heroics of the ship’s youngest crewman, George Sheldon, who became an instant hero, helping save the lives of the 30 crewmen. The exhibit, called “Icebound: The Ordeal of the SS Michigan” opened this past June.

“For the exhibit, I did some additional research to try to dig up more information about George himself, which unexpectedly led me to an incredible present day discovery that has completely rebuilt a local man’s family tree.”

To understand the personal story, you must understand the story of the SS Michigan.

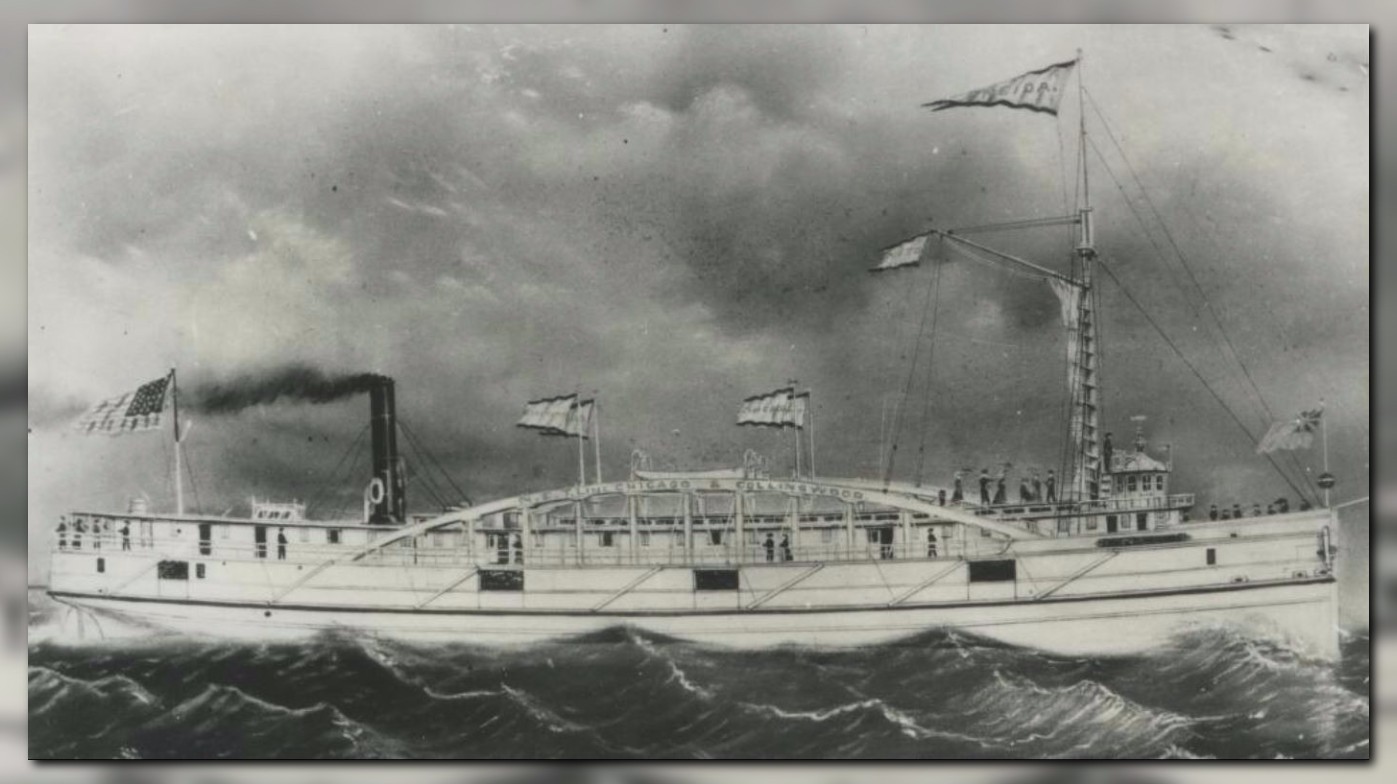

The steamship sank 131 years ago, and It now rests in 275 feet of water about 15 miles west of the Holland Harbor. It was a sturdy 204-foot long iron-hulled passenger steamer built in 1881.

“The Michigan had five water-tight compartments and a double hull with three feet of space between the two hulls, and her cabins were said to be the finest on the lakes and decorated without regard to cost,” said van Heest. The cabins could accommodate 123 passengers.”

The Michigan was owned by the Goodrich Line for two years, then it was sold to the Detroit, Grand Haven and Milwaukee Railroad Company in 1883.

On February 9, 1885, the Michigan left Grand Haven to assist another steamer – the Oneida – which had become stuck in the Lake Michigan ice.

“Captain Redmond Prindiville was the man in charge of the rescue mission,” van Heest said. “Prindiville put 29 men on board the Michigan. They expected to just go out, re-supply the Oneida, then come back to port.

“There was no weather prediction back then, so all of a sudden a winter storm came up unexpectedly, trapping the Michigan in ice before it could reach the Oneida.”

The next morning, Captain Prindiville realized that the Michigan was off South Haven, and the wind had blown it almost 40 miles south and 20 miles off shore.

“No one on land knew of their plight,” said van Heest. “They waited day after day, but the ice never loosened its grip on the Michigan’s hull.”

On Tuesday, February 17, after more than a week and with food supplies running low, the Captain made a decision to send 17 of the most hearty crewmen to make the trek across the ice, 15 miles to shore to inform the company of their plight and send a rescue ship to free the trapped Michigan.

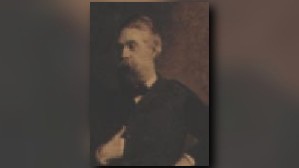

One of the men chosen was 21-year-old George Sheldon, who was the ship’s porter.

“The temperature was 10 degrees below zero when the men left the ship,” said van Heest. “But they grabbed their axes, pikes, ropes and rations, and began their journey around 7 a.m. that day.”

The first members of the crew reached shore around 5 p.m. that evening – 10 hours after they departed the Michigan. That group took shelter with local residents, then made their way to an Allegan County train station for the trip back to Grand Haven the next day.

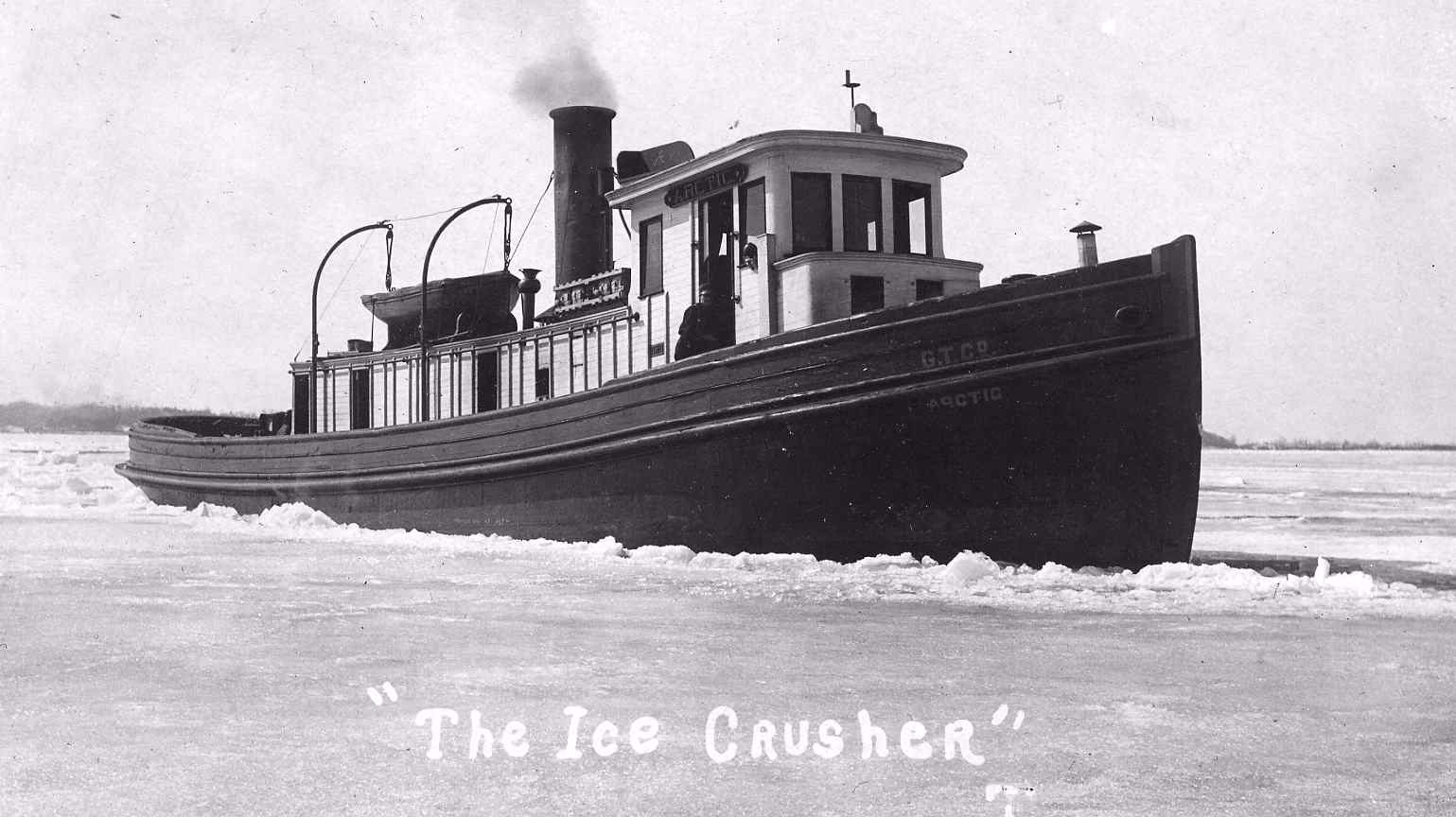

“Once the company learned of their ship’s plight, it readied their tugboat called the Arctic to travel out to deliver food and attempt to tow the Michigan back to Grand Haven,” said van Heest.

Worried his crewmates would not survive until the Arctic reached them, George Sheldon traveled back to Allegan, purchased supplies with his own money and headed back out to the vessel the following day with food, cigars, tobacco and newspapers.

“It took another 10 hours for Sheldon to make it back to the Michigan,” added van Heest. “Imagine the surprise of the crew when they were expecting a rescue boat but instead got George Sheldon, who literally was saving lives and didn’t know it at the time.”

Two days later, February 23, Sheldon packed a bag with a letter from the captain to his superiors, and once again set out across the frozen lake.

This time he made the trek in just five hours.

“The tug boat Arctic still hadn’t reached the Michigan yet, so George Sheldon knew more supplies and food would be needed for the crew to survive,” said van Heest. “Once he got back to shore, he made a trip north to Grand Haven to deliver letters and dispatches from the captain and crew.

“He then returned to South Haven on February 25, bought more food and supplies, commandeered five local men to help, and then headed back across the ice to the stranded Michigan.”

Soon after the men reached the Michigan, another winter storm blew in, bringing with it a strong wind out of the south, pushing the steamer north into another growing pack of ice, trapping everyone on board, including the helpers.

Several days had passed before the crew had realized they had been blown north and were now off the shore of Holland.

“It had been almost four weeks at this point, and even with the new supplies, the crew was running low on food again,” said van Heest. “Captain Prindiville made a very difficult decision; he had to send the five men from South Haven trekking back to shore on their own, dragging one lifeboat just in case the ice gave way.”

But, George Sheldon and the rest of the crew needed to stay with the Michigan in hopes of bringing the valuable ship safely back to port.

“On March 19, the 42nd day of being trapped, the Michigan was still locked solidly in the ice off Holland. The crewmembers heard the iron hull creaking and saw water start seeping into the ship,” said van Heest. “Captain Prindiville knew that they didn’t have long.”

Thankfully, on the horizon, Prindiville spotted the Arctic, but it too had become trapped in the ice before it could reach the Michigan.

“He readied one of the remaining lifeboats and prepared to abandon ship,” said van Heest. “Their only hope was to trek across the lake to the Arctic. It was about a four-mile walk.”

By dusk, they all made it safely to the Arctic, just in time to look back and watch the Michigan disappear beneath the ice.

“Now, the crew of both the Michigan and the Artic were trapped together, but did not have enough food to survive long,” said van Heest. “Captain Prindiville faced another difficult decision – the only way to survive would be to make the 15-mile trek to Holland. This was particularly dangerous considering it was early March, and the spring thaw was beginning to break up the ice.

“With experience on the ice, George Sheldon lead the way, and after a treacherous journey everyone made it safely to shore,” said van Heest. “Without George Sheldon, the crew of the Michigan likely would have perished.

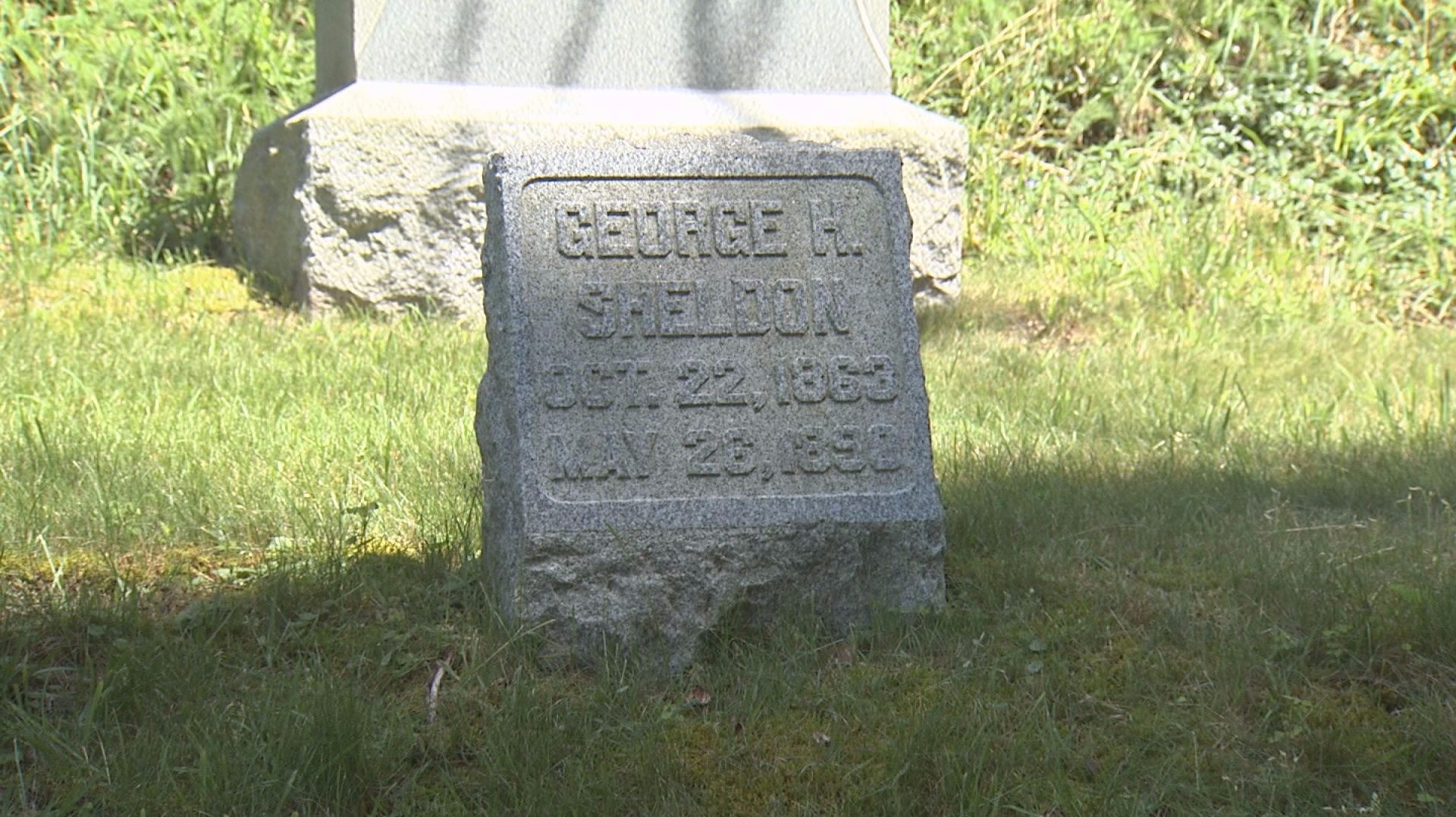

“George Sheldon is a true hero, but, sadly he lost his life at age 25, just four years after the ordeal on the Michigan. Historical records tell us that his health began failing due to his sufferings on the ice, and he died of Rheumatism in 1890.

George Sheldon was laid to rest in Grand Haven’s Lake Forest Cemetery.

Fast-forward 131 years.

“Before I started to design the exhibit, I wanted to do some fact-checking,” said van Heest.

She hopped on the internet to confirm background information about George Sheldon.

“I wanted to get the place and date of his death correct,” said van Heest. “I went back to Lake Forest Cemetery in Grand Haven and took pictures of his gravesite so I had the dates from his headstone, and then I did more research.

“I found something new in the cemetery records that had not been there when I did research for my book.” The post indicated that George Sheldon and his wife, Mary, had a daughter in 1890.”

The daughter’s name was Georgeann, and she was born just five days before George Sheldon passed away.

“I decided to research Georgeann Sheldon, and quickly realized that she had later married into the Conant family, and had children of her own,” said van Heest. “I then decided to take it a step further and started researching the Conant family and realized that members of the Conant family were still living in West Michigan today.

“One of George Sheldon’s descendants is Jason Conant, and my research showed that he was living in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Van Heest decided to pick up the phone and call Conant.

“I knew when I was dialing that Jason was the great, great grandson of George Sheldon,” said van Heest. “When Jason answered, I asked him about his ancestor George Sheldon and he said, ‘no, my great, great grandfather was named Leonard Raljah.’

“I said, ‘No, Leonard Raljah was your step great, great grandfather; your actual great, great grandfather was George Sheldon, who was a crew member on the SS Michigan.’”

Once van Heest provided Jason Conant with all of her research and genealogical information, he was amazed to learn this new information about his lineage.

“I was blown away when I found this out,” said Conant. “I have since told everybody who’s been willing to listen to me about this amazing connection. Mary Sheldon was my great, great grandmother. She remarried Leonard Raljah after George passed. We always assumed he was our great, great grandfather.

“At first I was skeptical, but Valerie knew a lot of information about my family through her research so that confirmed it.

“My grandfather was older when he had my father, and my father was older when he had me, so there’s a 100-year gap between when my grandfather was born and when I was born. I didn’t meet an entire generation of my family because of this, so there are a lot of stories from the past that have been lost, but I’m certainly glad that Valerie helped me find this one.”

Not only did Jason Conant discover who is true great, great grandfather is, he also found out the Sheldon name will forever be connected to Michigan maritime history.

“It’s hard to wrap your mind around,” said Conant. “He was just 21 years old when he went through that whole ordeal on Lake Michigan.

“This discovery has rekindled my interest in researching my family history because it’s opened a whole new chapter of my family that I never knew existed.”

Conant visited the exhibit at the Pump House for the first time in June 2016. He was alone in the room, moving from one piece to the next trying to comprehend how he and his family were all of a sudden thrust into this infamous Michigan maritime story. Conant shed a few tears as he viewed the various exhibits, knowing that his great, great grandfather selflessly saved 30 men from pending death aboard the ill-fated SS Michigan.

“Just to think, I’m related to somebody that did all this,” said Conant. “I don’t have any words to explain it.”

Jason Conant has three young children, so the story of George Sheldon and his heroic efforts aboard the SS Michigan will be told for generations to come.

The “Icebound” exhibit was so well received this past summer that it will remain on display at the Pump House through the 2017 season.

The Historic Ottawa Beach Society is seeking donations to help develop the building into a full-fledged museum. If you’d like to donate, click HERE and you’ll be taken directly to their home page.

If you know of a story that should be featured on “Our Michigan Life”, please send an email to: life@wzzm13.com.

Our Michigan Life airs weeknights on WZZM 13 News at 6.