WASHINGTON — Parents want to think of their home as the safest place for their children, but for some kids in D.C., it's not even safe to breathe there.

It’s a fall day in southeast D.C. A family of uniformed kids have returned home from school to their Forest Ridge apartment, ready to unwind.

Eight-year-old Trinity Johnson sits on the floor, building a puzzle with her brother, sister, and mom. Their little dog Bella bounces around them, prancing over the pieces.

Trinity laughs. She argues with them. She seems not to have a care in the world.

“Trinity is very feisty. She’s outgoing. She’s a talkative one. Um, she has a little spice with her,” said Trinity’s mom, Yolanda Pinkney, laughing.

But listen carefully, and you can tell Trinity's breathing is labored, wheezy – with that telltale rasp asthmatics know well.

“It’s like every time I sit down or like go anywhere, I cough, sneeze, and that’s what I do,” Trinity said matter-of-factly.

And that’s what she’s done. Nearly every day. For most of her life.

Trinity’s mom, Yolanda Pinkney, said doctors with Children’s National Hospital diagnosed her daughter with asthma a couple years ago. But, she said, her daughter has been sick since they moved into their first apartment at Forest Ridge when she was a toddler.

"When she was about 2 years old... it started getting progressively worse,” said Pinkney. “Like, she started being sick longer or more, or it would have to be a trip to the emergency room instead of just some over-the-counter medicine.”

She said about four years ago they moved to a different unit in the complex, where they live now, and conditions have only worsened.

“Nobody should live in some conditions that certain people are living around here,” said Pinkney.

When WUSA 9 first visited her apartment on Pomeroy Road in July 2019, she took the team on a tour of problems – mostly congregating in her tight, poorly ventilated bathroom.

Pinkney pulled back the shower curtain to reveal a gaping hole in the wall around the shower head that she said had been that way for months. There were black and brown spots that she referred to as mold growing all over the ceiling. And the vent on the wall was completely clogged. She said it had been that way for years.

“It’s always a lot of coughing in here,” said Pinkney. “We have to keep Lysol, you know, we have to wipe down. Clorox wipes. We have to wipe down a lot. It’s like a constant bleaching.”

Conditions in Yolanda Pinkney's Forest Ridge apartment

Plus, she said, Trinity has to take multiple medications every day just to ensure she can breathe.

She said no matter what she tried to do, Trinity kept getting sick. She said the ER visits were becoming monthly, causing Trinity to miss school and her mom to miss work to take care of her.

After one-too-many trips to the ER, she said a doctor referred Trinity to the IMPACT clinic, a pediatric asthma program run by Children’s National Hospital. The clinic gives doctors a chance to educate parents in a one-on-one setting. In each consultation, a medical professional sits down with families and discusses asthma triggers and potential solutions.

Doctors said they quickly developed evidence that unhealthy homes correlated with some of the children's persistent illnesses.

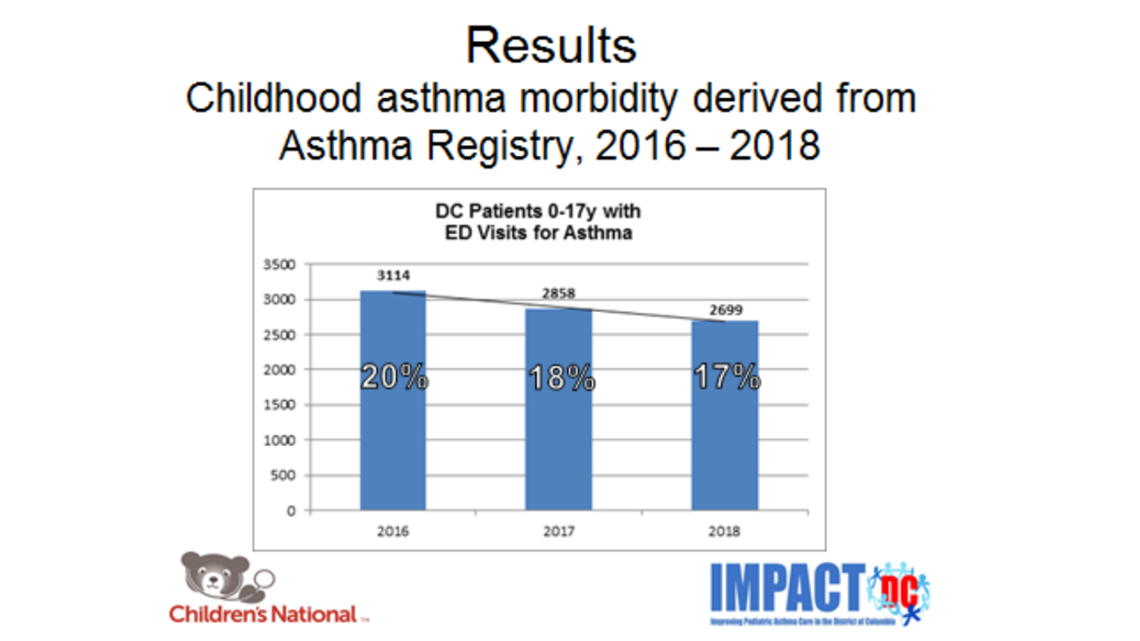

Doctors with the clinic said D.C. has a disproportionately large number of kids suffering from asthma. Dr. Shilpa Patel, who serves as an attending physician of emergency medicine at Children’s National, said there are about 17,000 children with diagnosed asthma living in D.C.

Children's National reported that 5,584 pediatric patients went to the emergency department at Children’s National for asthma symptoms in 2019. A spokesperson for the hospital said nearly 3,700 of the visits represented kids from D.C.

The spokesperson also said that children from Wards 7 and 8 had 20 times the emergency department visit rate for asthma compared with children living in Northwest D.C.

The clinic’s latest study, which covers data collected from 2014 through 2017, reports that nearly 25% of pediatric asthma patients said they are living in unhealthy homes – meaning houses with mold, rodent or pest infestations, poor ventilation, moisture or dust.

"Asthma results in 13 million missed school days for children every year nationally,” said Dr. Shilpa Patel. “That’s a significant statistic, so if we want our children to succeed, and asthma, as you said, is so common in Washington, D.C… we need to fix this problem so they can attend school and be successful.”

After hearing stories like Yolanda Pinkney’s, and about multiple safety violations from D.C. police, the D.C. Attorney General's Office decided to file a lawsuit against multiple landlords in the District in October 2018. One of the target apartments was Forest Ridge, a 399-unit complex located in Ward 8.

The lawsuit says that the “defendants have operated the Properties ‘in a manner that demonstrates a pattern of neglect’ dating back many years.” They cited “a multitude of recurring and continual code violations,” like “bedbug and rat infestation, sewage leaks, inadequate heating and life safety facilities, and mold contamination due to unidentified leaks.”

The lawsuit says that the aforementioned conditions “pose a serious threat to the health safety, or security of the tenants and their families.”

“We’re sitting here waiting in limbo to see what’s going to go on,” said Pinkney. “And while you’re sitting there waiting, your children are still breathing in the same toxins, having the same issues, still going to the same doctors, you know, dealing with the same things. So it’s like, 'What do you do?'”

With encouragement from Trinity’s doctors, Pinkney reached out to Children’s Law Center, which set her up with a pro bono attorney to push for change on the legal side.

Pinkney said she had been trying everything she could think of to get the problems in her home resolved on her own.

“I called maintenance… we can’t tell you when they’re coming,” she said. “I’ve had DCRA come in, they do an inspection, they violate them… They say fines, fines, fines. Nothing’s happening.”

WUSA9 reached out to the current owner of Forest Ridge, Joseph Kisha with Vista Ridge LP and Castle Management, multiple times and never received a return call.

DCRA said they have issued $18,000 in fines on Pinkney’s behalf and have done all they can legally do.

To be clear, DCRA refers mold complaints to DOEE. But, the agency said it discovered multiple other issues in Pinkney's apartment, too.

“Sometimes you feel like you failed,” said Pinkney. “Sometimes you feel determined to get them out of here.”

Senior supervising attorney at the Children’s Law Center, Kathy Zeisel, said part of the issue is the type of contract the Forest Ridge owner has with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. It’s classified as subsidized housing, but Zeisel said the subsidy is tied to the apartment complex, not to the tenant.

“At a place like Forest Ridge, which is a kind of subsidy where the family can’t really leave the property, it puts families in the hard place of choosing being homeless, because they can’t afford to move off the property, or sort of rolling the dice on maybe this property will be better,” Zeisel said.

So, Pinkney doesn’t receive a voucher that she can use anywhere. If she wants to take advantage of the income-based subsidy, she has to stay at Forest Ridge… or go through an entirely different application process.

“I’d rather deal with the devil I know,” said Pinkney.

She said maintenance did make some mold fixes to her unit back in October, but the mold is gradually growing back months later.

Other tenants shared similar problems when WUSA9 visited Forest Ridge again in October.

“My son, [who] is premature, he was born at 34 weeks, he’s constantly getting sick in here, runny nose, coughing, and I really think it’s ‘cause of this apartment,” said Latisha Johnson, who lives in a top-floor apartment.

Johnson faces many of the same problems as Pinkney.

She pointed out poor ventilation, mold problems and swarms of gnats circling the kitchen and bathroom.

“A lot of nasty stuff, lots,” said Johnson.

Another neighbor who lives on the first floor, Imani McKoy, said she noticed mold growing on her bathroom ceiling, too.

McKoy said maintenance patched the surface, but she’s confident that the root problem still exists.

“So, it’s like nothing I can do but just wait for the mold to come back and deal with it,” said McKoy.

There is a beacon of hope on the horizon.

Real estate consultant Belveron said they are going to be part of a new ownership group taking over soon. A spokesperson said they are planning to gut the place and do a total rehabilitation.

They said they will be working with local companies to make sure tenants have a place to stay during the remodel.

“I love my kids,” said Pinkney. “I think they deserve to have a healthy home. I think they deserve a safer neighborhood. I think they deserve a chance like any other child.”

Trinity’s wish is simple: “Better stuff than this home.”