Dying to give birth: That's what's happening in hospital rooms across America. Too many women are dying after childbirth, but it's happening more often for black mothers.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, black women are three to four times more at risk of dying from pregnancy-related causes than any other race.

'The last thing I told her is that I loved her'

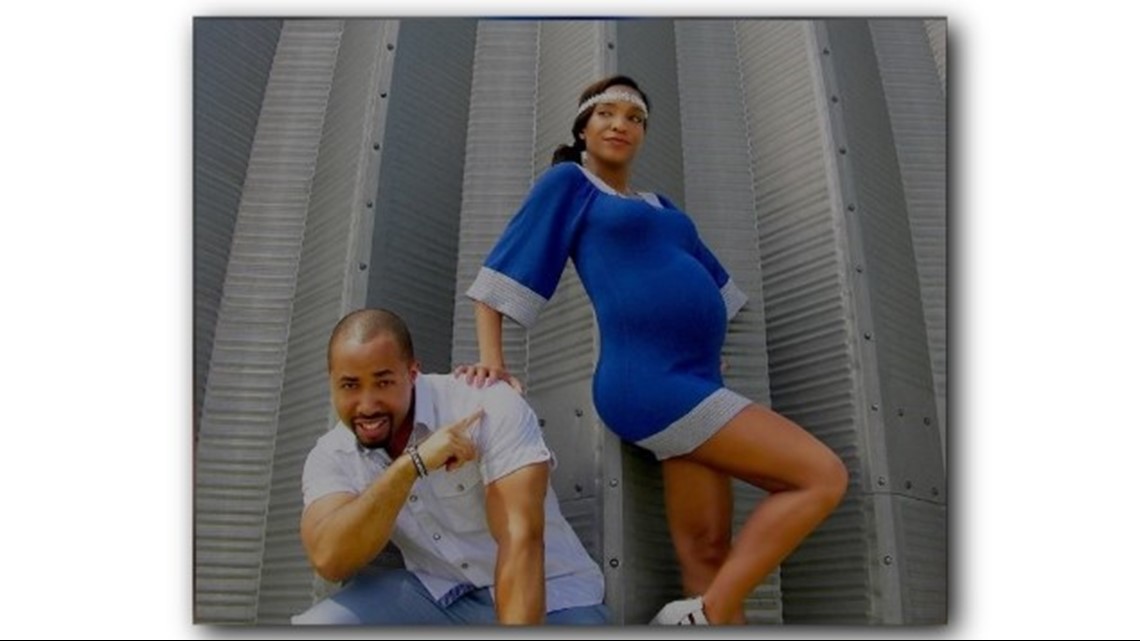

For Kira Johnson, a black mom, her life ended less than 12 hours after the birth of her second child.

All signs pointed to a healthy delivery, said her husband, Charles Johnson. She never missed a prenatal visit, and received great reports each time. She gave birth to a healthy baby boy.

Then Charles made a disturbing discovery: blood in Kira’s catheter.

After waiting for hours, Charles said, Kira was taken back for an internal exam. He never saw her alive again.

She died from from a hemorrhage.

"When they told me that her heart stopped, that was all I heard," said Charles Johnson.

Kira's mother-in-law, Glenda Hatchett, said their family never thought this could have happened.

"What I know is that I walked into that hospital never imagining that she wouldn't come home," Hatchett said. "And I did not know that this is such a horrible crisis in America."

'Do you think it was because she was black?'

Charles Johnson said he's asked a lot if he thinks race was a factor in his wife's death.

"The way I answer that question is: the simple fact that you have to ask that question is a problem."

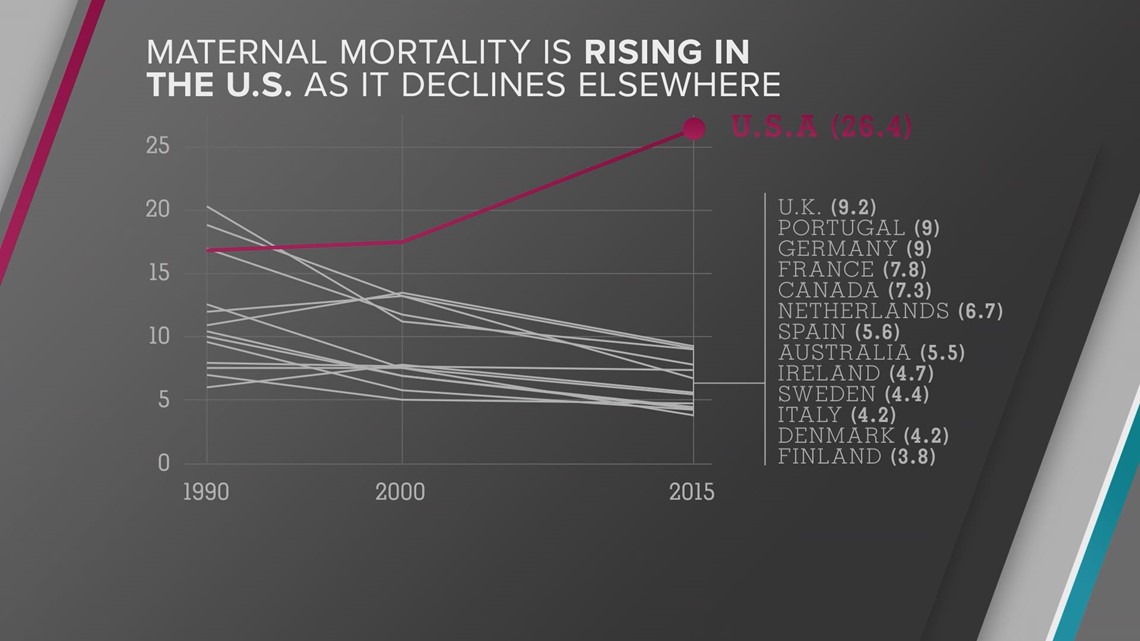

A CDC Foundation Report found the rate of women dying from childbirth is rising in the United States while it's dropping in other countries around the globe.

The CDC defines a pregnancy-related death as a woman who dies from complications aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes. The death can occur during the pregnancy or within one year after the delivery.

For every 13 white women who die during pregnancy or within one year of giving birth, there are 44 black women. Most of these deaths are preventable.

“The experience of being black in America is so fundamentally different from the experience of being white in America that it translates to health outcomes,” said Dr. William Callaghan, chief of the CDC’s Maternal and Infant Health Branch.

"Black women are three to four more times more likely to die than white women in the United States. And the only difference is the color of one's skin."

In states like Georgia, which reports the highest number of maternal mortality deaths in the country, 755 women died from pregnancy related causes from 1999 to 2016; 413 of them were black.

Black women die at higher rates regardless of their education, how much money they make or pre-existing conditions. Dorothy Roberts, the director of the Penn Program on Race, Science & Society, believes the reason for the racial disparity is directly tied to racism.

“You know some people hear those statistics, and they'll say, 'There's something wrong with black women - it must be some gene that black people carry that causes it,'” said Roberts. However, she said it has noting to to do with genetics.

“All of this is racism. It’s various types of racism,” Roberts said. “They go to all their prenatal appointments. They are in good condition when they arrive at the delivery room, and then they experience racial discrimination by medical professionals."

Several studies compare the medical treatment black patients received with other races. A 2015 study published in The Journal of the American Medical Association found black children received less pain medicine when treated for the same condition.

Another study published in the AMA Journal of Ethics found pain treatment is strongly influenced by race and ethnicity as well as by the social and economic conditions in which people work and live.

Roberts believes these studies shine light racial stereotypes held by doctors that affect how black patients are treated.

"This idea that black people have different kinds of bodies than other human beings has continued in medical practice to this very day," she said.

'We just don't feel that we practice medicine that way'

Doctors take an oath to treat all patients equally and most would defend their unbiased care. Many medical professionals disagree with the claim that race negatively impacts care.

“We have a huge African-American population of patients, and I have no doubt in my mind that we give them the exact same care as anybody else," said Dr. Sujatha Reddy, a specialist in women’s health. "When I brought this up to my partners, it was almost hurtful because we just don't feel that we practice medicine that way."

Reddy noted several genetic differences that are taught in medical school to help doctors better care for patients of a specific race.

"I'm Indian, we're prone to cardiovascular disease," Reddy said. "If I recommend a colonoscopy to an African-American person at 45, does that make me racist? I don't think so. It's actually better health care...if you know that in this race, these things are more common..."

She said other medical conditions having nothing to do with racism can contribute to pregnancy-related risks.

“I think the fact that we're seeing all patients are heavier. Being overweight and obese is fraught with other medical complications like diabetes, high blood pressure, which increase your risk of delivery complications and increase your risk of postpartum complications,” Reddy said.

For thousands of women, those problems lead to lifelong consequences. But they don't have to be deadly.

►PREVIOUS CHAPTER: She went to the hospital to have her baby. Now her husband is raising two kids alone