PRINCE GEORGE'S COUNTY, Md. — Five-year-old Amani started to sob during her virtual kindergarten class. She was having an “emergency" – a papercut emergency. The problem was her mother was also in class. She teaches high school English virtually for Prince George’s County, and the sobbing was getting louder, invading her own classroom.

“What's wrong with you?” her mom, Geva Hickman-Johnson called from across the room.

The sobs continued.

“Hold on,” she said to her students over Zoom. “I've got a whole situation. Oh my word!”

After some quick “mommy first-aid,” Hickman-Johnson, or "Miss. J," as she's known to students, got back to class. Thus is the life of a teacher during the pandemic's virtual school.

“I was able to save the finger, guys, we can move on,” she joked.

Below, Geva Hickman-Johnson quickly pivots from teacher to mom to triage a papercut:

The distractions of teaching from home aren't the only concerns on Miss J's mind during the COVID-19 pandemic. She worries it will lead to a decrease in education funding.

In Maryland, some of that money comes from gambling and is put into the state's Education Trust Fund. The public health emergency forced casinos to close this spring. Data from the state shows no money went into the fund in April and May. When casinos reopened in June, their capacity was limited, and so was their revenue. There would be no jackpot for schools.

A WUSA9 investigation shows at the end of fiscal year 2020, which closed out in June, the fund had a deficit of $22,762,114.

“We're expected to do without and now you're expecting us to do without, plus without some more,” Miss. J said. “It's hard. It's hard and it's scary because at the end of the day, we all want what's best for our kids.”

We asked the Maryland State Education Association what kinds of concrete consequences this could have. They believe the deficit could mean: increased class sizes, less school staff, less support professionals who help students and less school counselors and psychologists.

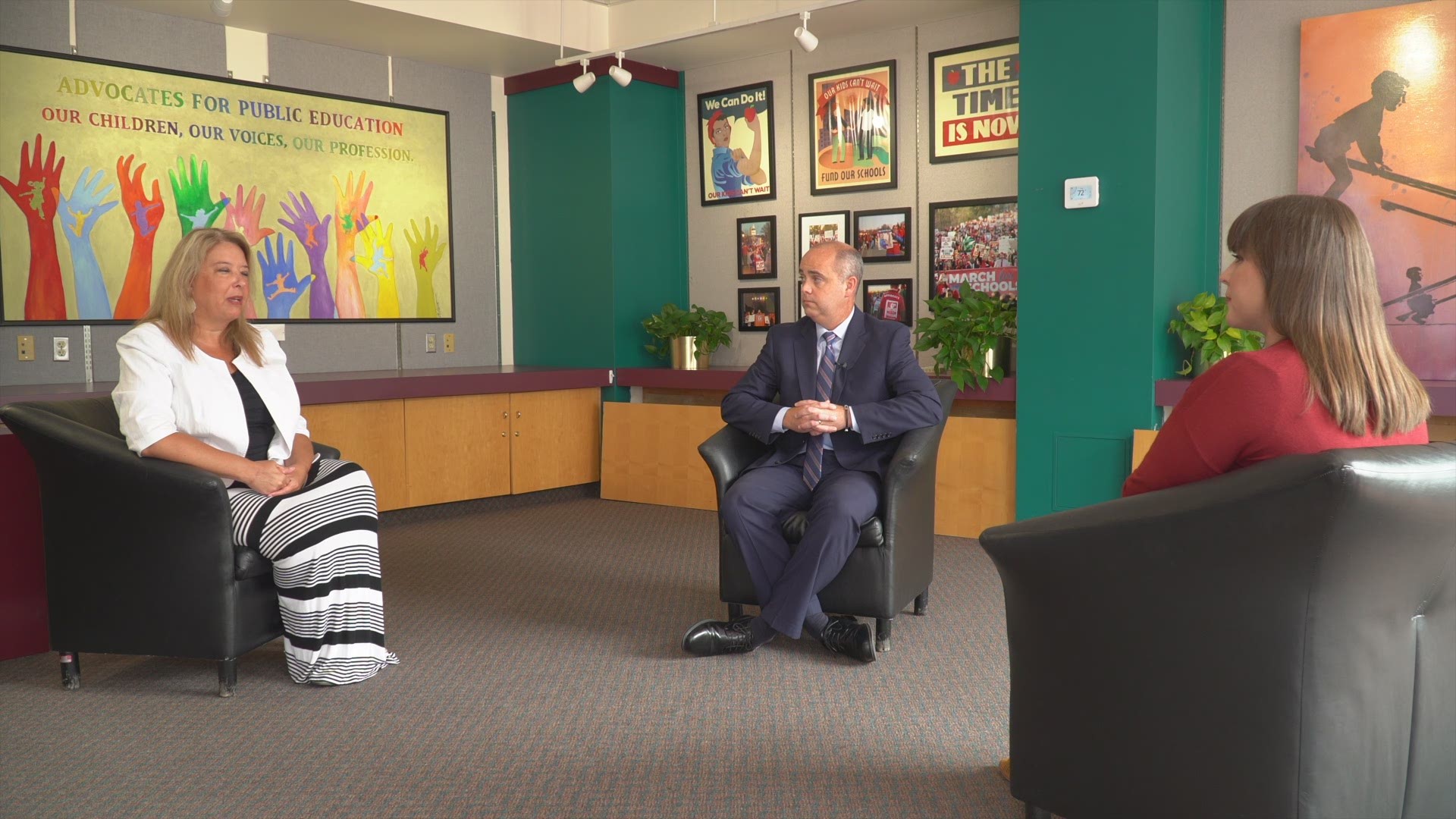

And, there are concerns there could be even more cuts, according to MSEA President Cheryl Bost and Executive Director Sean Johnson.

“We are not spreadsheet governing here,” Johnson said. “What it really is, is a gap in people, programs and services that are desperately needed, and I just want to make sure that we don't lose sight of what those dollars are investing in.”

This comes at a time when educators are weighing fears about bringing students back into school buildings and implementing costly pandemic safety protocols.

“That's a lot of stress,” Bost said. “Students, we hope, don't feel that stress. We want to be back in school. We want to be together. We know that we offer the best education when we're in person, but it has to be done in a healthy and safe manner and to do that we need additional resources and not the fear of seeing more cuts.”

Below, MSEA President Cheryl Bost talks about teachers' fears as budget talks loom:

As Miss J closed out fifth period, she worried about the future.

“If you don't take care of your students, the students of Prince George's County, they then become your constituents of Prince George's County, who are now not completely educated,” Miss J said. “They have not been given the tools that they need to become successful constituents in your community, which means they then can become an additional drain on an already struggling system. So, it’s a vicious cycle.”

Below, Geva Hickman-Johnson leads her students in virtual learning:

Budget talks have already started, but they won't fully ramp up until the General Assembly session in January. That's when we'll get a more concrete picture of exactly what these shortfalls mean for Maryland students and teachers.