WASHINGTON -- "It changed my goals, my plans," said Christi Haynie, repeatedly succumbing to tears. "It changed the course of my life. It changed my personality. It changed the root of my being."

The former Peace Corps volunteer couldn't hold back her emotions when she discussed the life-altering side effects of the antimalarial pill, mefloquine, and its devastating impact on her family.

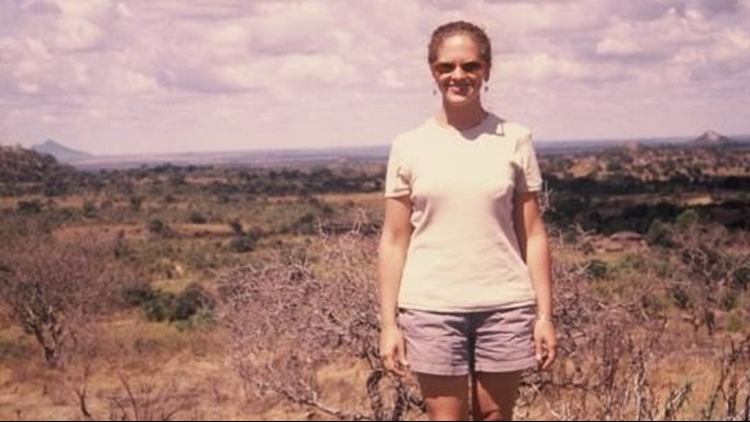

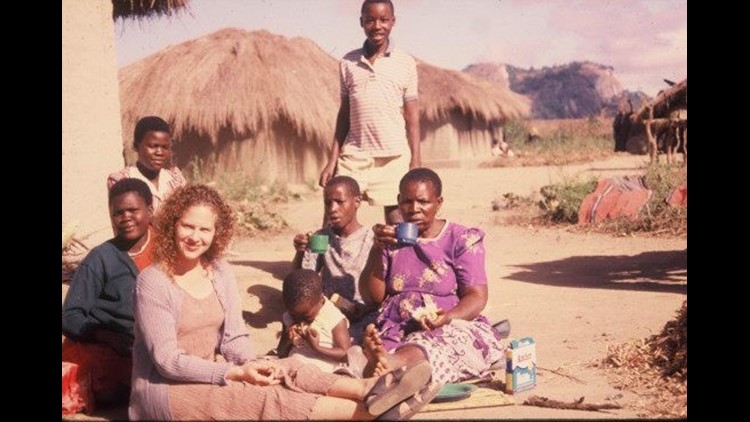

The Peace Corps had prescribed the weekly medication during her service in Malawi from 1996 to 1997. It was intended to prevent malaria, a mosquito-borne disease that can be fatal. But in Haynie's case, documents confirm, it did so much more.

"If I had known that if I became depressed or I became anxious, I should discontinue the medication immediately, I would have," she said.

But according to Haynie, the Peace Corps medical staff never told her to stop, despite her immediate onset of severe depression, anxiety and paranoia. That’s even noted in the product warning label as a reason to discontinue use.

Haynie recalled the Peace Corps attributed her extreme physical and psychiatric side effects to “adjustment issues to life overseas,” an odd conclusion because she was already a seasoned world traveler. It was 15 years later, when she requested her medical records, she noticed the Peace Corps had cited “a possible adverse reaction to mefloquine” as she was medivaced out of Malawi.

After taking mefloquine, extensive medical records confirm that the happy, outgoing former gymnast and cheerleader became a shell of her previous self. Haynie transformed into a medically-fragile woman with thoughts of suicide.

PHOTOS: Former Peace Corps volunteer says anti-malaria drug has shattered her family

"I never attempted it, but I have certainly been depressed enough to that point," she described, wiping tears from her face.

She was even diagnosed with damage to her brainstem—a devastating, irreversible side effect found in fellow Peace Corps volunteers, according to medical records, as well as veterans who have taken the drug, as documented in our year-long investigation.

"It’s very hard. Knowing her so well and what she was like in the past, it’s almost a 180 degree turn for her," said her husband, Johnny. The family asked that his last name be withheld. He has known Christi for 30 years.

"I’ve had to take on a lot myself because there are times that Christi just… she can’t function," he said. "She’s best suited to be in bed for two or three days at a time. That’s the most difficult part for me."

The couple has three sons. Mefloquine impacts their lives too.

"We just try to help her a lot. It’s kind of hard sometimes, but we try our best. Keep the noise down. Keep the light down. We have to kind of stand still sometimes because if we sway, it will make her dizzy. Try to help her with everything that she needs," says 12-year-old Hudson.

He added, "I think I love her more than lots of things in the world. Like everything."

The Peace Corps' Director of Epidemiology Dr. Kyle Peterson defended the use of mefloquine, and repeatedly noted that malaria was a deadly disease.

"We do know that people who take mefloquine 60% of them have no symptoms," he said. That indicated, however, that 40% of those prescribed the weekly pill did suffer side effects, a seemingly high percentage.

"Right and that’s why this is a black box warning," responded Dr. Petersen.

That warning by the FDA was the strictest alert on a prescription drug label that noted evidence of a serious hazard. Issued in 2013, it came too late for Haynie. But it did prompt a major policy change for the Peace Corps. Volunteers may now choose their own antimalarial medication.

Added Dr. Petersen, "The only thing you have to know about the black box is that you have to do this safely. You can’t just willy nilly hand out prescriptions to patients and not supervise them or inform them."

But Haynie and dozens of other former Peace Corps volunteers alleged that was precisely what happened to them.

"Unfortunately, malaria is a deadly parasitic infection. It’s a tropical infection that afflicts 200 Million people annually and almost half a million people die," said Dr. Petersen.

Despite strong support from her family, the welfare of others who took mefloquine still haunts her.

"I believe knowing is half the battle," she stated, and again struggled to contain her emotions. "I really want Peace Corps volunteers, veterans, world travelers who have taken this medication to not to despair. Not to give up."

PREVIOUS INVESTIGATION: Vets say anti-malaria drugs they were ordered to take caused devastating side effects

Haynie’s goal had been to work for the State Department, and ultimately become a diplomat. That dream, like her good health, is gone.

Mefloquine is still licensed by the FDA and available in the United States with a prescription. The manufacturer of the brand name Lariam stopped making it in 2008.

Only one manufacturer continues to produce a generic version of the drug. Teva Pharmaceuticals declined to comment for this report. Four other generic producers of mefloquine have discontinued the drug.

WATCH: A Peace Corps epidemiologist defends the agency's prescribing of mefloquine to prevent malaria.