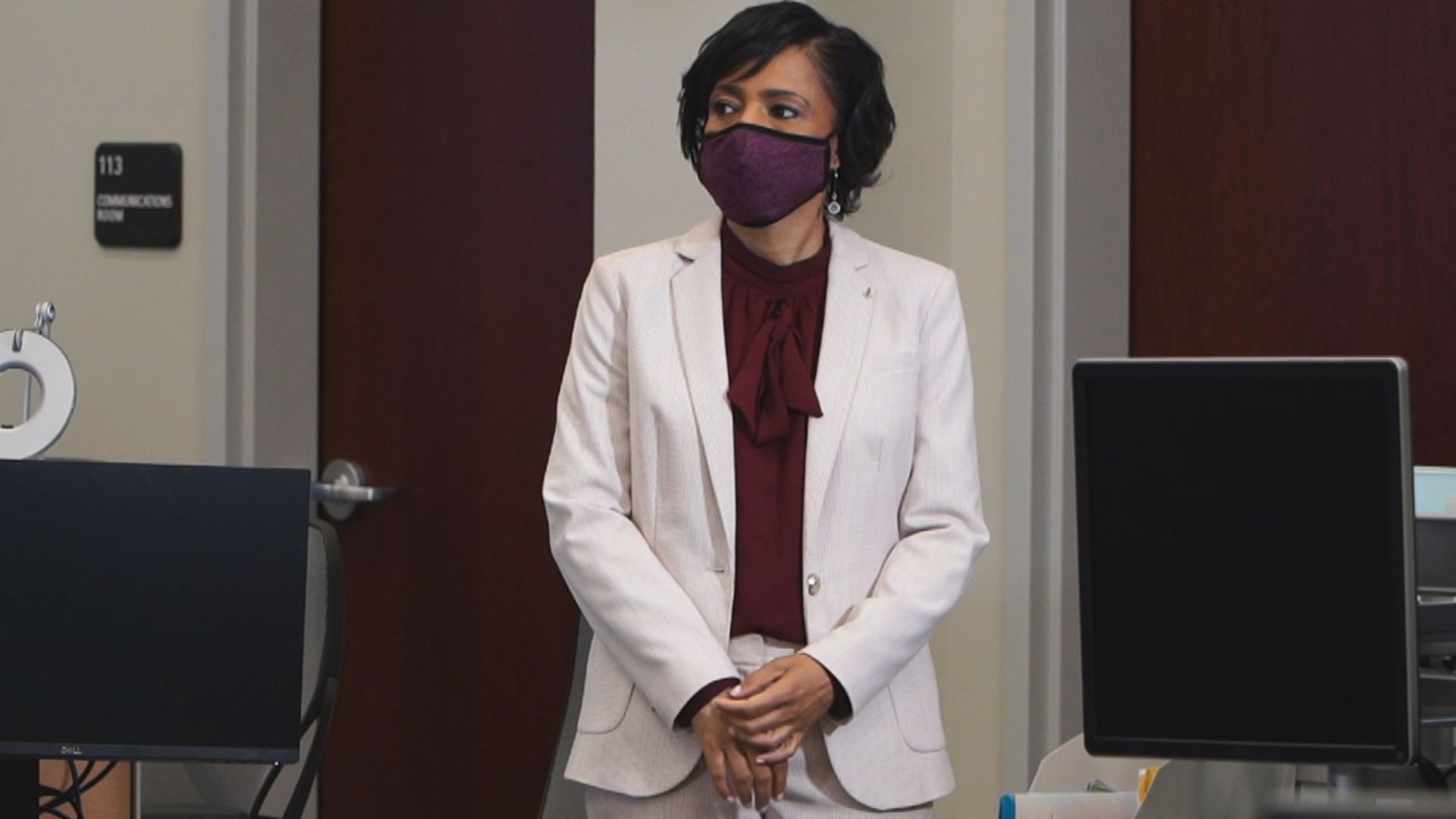

PRINCE GEORGE'S COUNTY, Md. — As Angela Alsobrooks navigates through the orange cones and caution tape guiding her county's residents toward a COVID-19 vaccine, her shoulders visibly relax. The masked Prince George's County Executive stops to chat with vaccination volunteers and shot recipients alike, offering elbow bumps as a token of her thanks. After 13 months of sickness, death and charting unknown territory, she's seeing a path out of the dark.

"Last year around this time, I was petrified," she said, pausing for a beat. "I was ... frightened. Now I'm hopeful. I see the light."

But the Maryland native has not taken her foot off the gas, keeping her sights set on seeing Prince George's through to the other side of a pandemic that has devastated her county at greater rates than anywhere else in Maryland.

"I could have never in my wildest dreams," Alsobrooks starts to say. "Of all the challenges I thought I would have, this is not anywhere close to what I would have imagined."

More than 80,000 Prince Georgian's have been diagnosed with COVID-19 since March 2020, and close to 1,400 community members died. According to Alsobrooks, the structural inequities that she's been fighting since the day she was elected were only exasperated by the arrival of COVID-19.

County Executive Angela Alsobrooks

The virus still consumes much of her time -- and emotion. Her days now are spent balancing news conferences — where she continually provides updates on COVID-19 data and county health progress — with visits to vaccination clinics, where she can see firsthand how Prince Georgian's are responding to her vaccine promotion efforts.

“How did it go?" Alsobrooks asks a woman who received her first vaccine shot at the Kentland Community Center Vaccination Site.

"I'm doing just fine" the woman responds cheerfully." You didn't hear any screams."

Alsobrooks said responding to COVID-19 was tougher for Prince George’s County than other counties in the state. Structural issues with access to health care and health disparities meant COVID-19 had more opportunity to disproportionately sicken residents who are already dealing with high rates of chronic health conditions like diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure.

“During this pandemic, we were sicker than anyone else in the state," Alsobrooks said citing the county's case rate — the highest in Maryland. "And guess what happened? We had to bring tractor-trailers into the parking lot of the hospital to care for people who needed ICU space."

Inequity is an issue that hits close to home for Alsobrooks. Social inequity brought her family to Maryland in the late 1950s.

"My great-grandfather was murdered in Seneca, South Carolina by a Sheriff’s Deputy — my mother was 9 at the time," Alsobrooks said, her voice cracking. “This was a very devastating occurrence for our family. We were told if the whole family didn’t leave, they would kill the whole family. So, my family came, about a week after that, up North.”

Alsobrooks has been working to address the relationship between law enforcement and the community following the death of George Floyd and after allegations of discrimination were lodged against the Prince George’s County Police Department. In February, she pledged to adopt 46 of 50 recommendations proposed by the Police Reform Work Group, which include updating policing strategies and committing more resources to mental health services.

Some of that recent legislation includes restricting no-knock warrants, a statewide use-of-force policy, giving the public access to records in police disciplinary cases and mandating body cameras statewide by 2025.

“No one was ever held accountable for the murder of my great grandfather," Alsobrooks said. "The legislation that we saw in Annapolis recently allows us to hold accountable officers that need to be held accountable.”

RELATED: Activists call for removal of top officials after PGPD report alleges racism and retaliation

As Alsobrooks continues to work to address bias in her 9-5, she comes home to an inquisitive teenage mind, learning a few hard lessons of her own.

"She said to me, 'I now understand something about America that I didn’t understand,'" Alsobrooks said, recounting a conversation with her 15-year-old daughter Alex after the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. “'I cannot understand why the people who stormed the Capitol could do so without consequence. I just know if it were someone who looked like me, the results would be so much different.'”

Alsobrooks looked pensive for a moment as she reflects on how inequity has wormed its way into every facet of her life. But she quickly recovers, because if there's one thing political life has taught her, it's that there are a lot of eyes on women with as many "firsts" on their resume as hers. She's Prince George’s County's first female state’s attorney, its first female county executive and she's the only Black woman currently leading a Maryland county.

But now, many are wondering if she could break yet another glass ceiling, and become Maryland’s first female governor.

“What an honor it is to be considered," Alsobrooks said demurely when asked what it would take for her to throw her hat in the ring of the gubernatorial race. "There’s a time and season for everything. We’ll see what the season is."

Sign up for the Get Up DC newsletter: Your forecast. Your commute. Your news.

Sign up for the Capitol Breach email newsletter, delivering the latest breaking news and a roundup of the investigation into the Capitol Riots on January 6, 2021.