WASHINGTON -- "It has completely 100% changed my life," said Felicia Kenney, a former Peace Corps volunteer who served in Benin from 2003 to 2004.

"I can no longer work. My psychologist doesn’t believe I will ever work again," she said. "I can barely handle taking care of myself, feeding myself."

Her downward spiral is directly linked to her Peace Corps service, according to medical records. Kenney said she was told to take mefloquine, a weekly pill to prevent malaria. No one, she insisted, warned her of potential physical and psychiatric side effects.

"Every aspect of my life is a challenge," she told us via Skype. "All I want to do is go back to work and I can’t."

Prior to joining the Peace Corps, Kenney was a successful computer programmer and an honors graduate of an Ivy league university. Since then, she’s struggled with anxiety, depression, and problems with her vision and balance. Kenney's medical records revealed she suffered traumatic brain injury from “Larium (sic) poisoning.” Lariam was the brand name for mefloquine. Its manufacturer stopped producing it in 2008.

"Not only did they not warn us, I mean NO warning, like they gave you the pills, you took them, that was it," she recalled.

Dr. Kyle Petersen, the Director of Epidemiology for the Peace Corps, defended the agency's actions.

"Judging by what was available on the market at that time, Peace Corps did the best job that they could. We’re talking about a disease that kills people," he said.

"This is foolish! They lied right to our faces," argued Kenney, who alleged her repeated concerns about the antimalarial pill were dismissed by the Peace Corps.

"And the thing is I later talked to some people who had served previously in the region, and they had had similar doctors and they had had problems with mefloquine," she said.

For decades, the Pentagon prescribed mefloquine for military service members deployed to malaria-prone parts of the world. But since 2013, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued its most stringent warning about potential side effects, the Pentagon now issues it only as a drug of last resort. But not the Peace Corps.

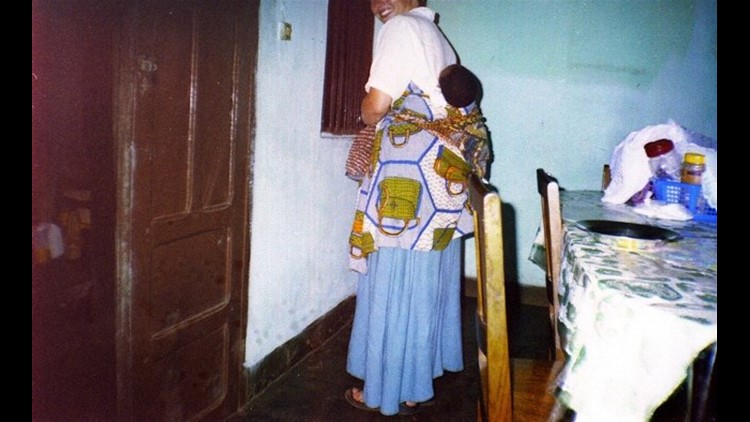

PHOTOS: Peace Corps volunteer says anti-malaria drug has made her life a 'challenge'

Dr. Petersen pointed out, "Peace Corps volunteers serve in West Africa and Central Africa, which are some of the most malarious countries on the planet, so it’s quite a bit different in terms of the rate of risk for malaria in our volunteers compared to military members who have mostly been serving in the desert."

That was little consolation for Kenney, who can no longer handle loud noises, bright lights and overt displays of emotion. She and her husband researched locations around the world where the population was generally subdued. They moved to St. Petersburg, Russia.

PREVIOUS INVESTIGATION: Vets say anti-malaria drugs they were ordered to take caused devastating side effects

Through the Department of Labor, Kenney has received $21,000 a year in disability payments, but she has no medical insurance.

"They wouldn’t have to pay me if they had been honest," she said.

WATCH: A Peace Corps epidemiologist defends the agency's prescribing of mefloquine to prevent malaria.