Saving a Generation | The new face of drug addiction

The new face of addiction is often not what you pictured. The new face of addiction is changing, growing, and devastating families all across the country. It's a problem that affects every household in Arkansas. So, we wanted to take you on a journey. A journey that will show you the impact addiction has on us all, the fight against it, and the road to recovery. We are working to save a generation.

The Faces

Addiction has many different faces. The faces can be any color or any social class. The faces can be short, long, fat or skinny. It can be anybody. Whether those faces belong to people who are struggling personally or it's their family and friends, they are different.

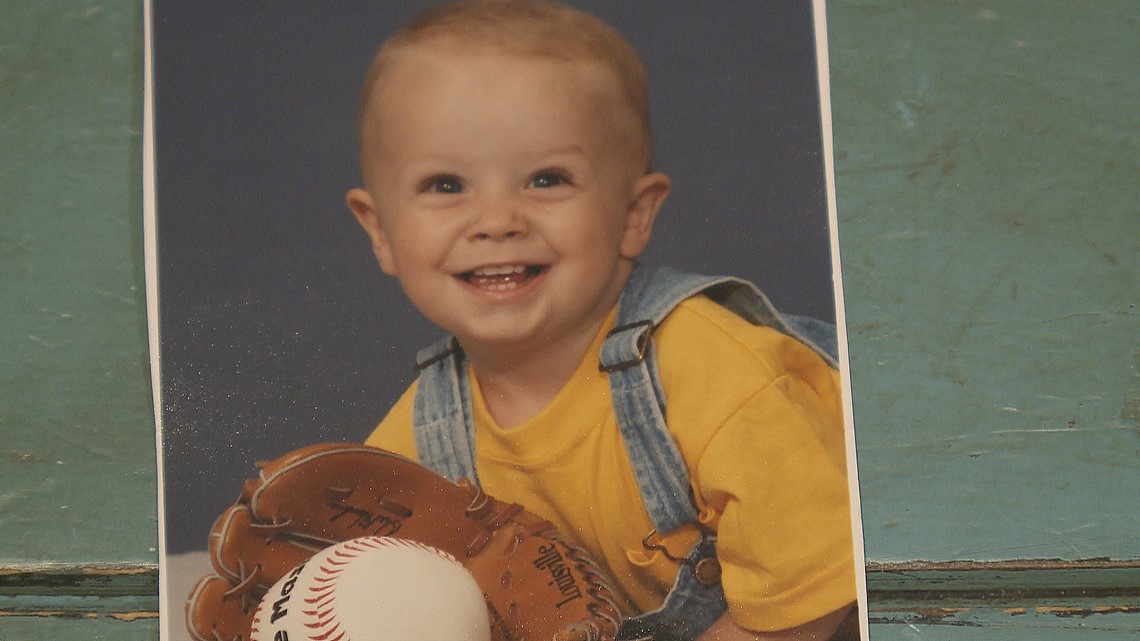

No story is the same. Situations may be similar but those lives are unique. Those stories are their own, including that of Parker Patterson from Prairie Grove, Arkansas.

“Parker was the life of the party. Whenever Parker was around you knew it wasn't going to be a boring time,” said Parker’s mother, Andrea Patterson. Parker was a big brother, who his mother said was protective of his sisters and always looked after them.

“He was funny. He loved to make people laugh. And he never walked out the door without giving you a hug and saying I love you mom,” she told us.

Andrea was very close with her son. He would tell her a lot of things that she didn’t necessarily want to know, including that he started smoking marijuana at the age of 14.

“I don't believe he did much more than that. Until at least a couple of years later,” she said. Andrea believed the drugs started as an escape for Parker, from his ADHD, anxiety. “I think that had a lot to do with why he used.”

In March of 2015, Andrea became fed up with Parker’s drug use and didn’t want her other children to be impacted by his choices, so she kicked him out of the house. But Andrea said their relationship didn’t change.

“He wasn't angry," she said. "He still came around. We still talked every day.”

But that didn't deter Parker from using drugs. That summer is when Andrea said she knew for sure that Parker started doing other dangerous drugs.

Just months later, on October 12, 2015, there was a knock at the door of the Patterson home. The police had come to tell them that Parker overdosed on methadone and was rushed to the hospital where he died two days later.

Parker Clay Patterson was just 18 years old.

No words could properly explain the way the Patterson family felt after his death. The only thing that could come close to describing is that it was a "nightmare."

“It still doesn’t seem real," Andrea said. "Even though I have relived it over and over.”

Andrea said there is just a peace you have knowing all of your children are at home and that they are safe. “When Parker passed away I kept thinking I am never going to feel that way again. It’s never going to be the same. And it’s not.”

Losing someone to drug addiction is a pain that many could never imagine happening. For the family of Jake Agar, the heartbreak still affects them to this day.

As his family would put it, Jake was the kind of guy that all the girls wanted to date and all the guys wanted to be. He was a kind and passionate person who cared about everyone.

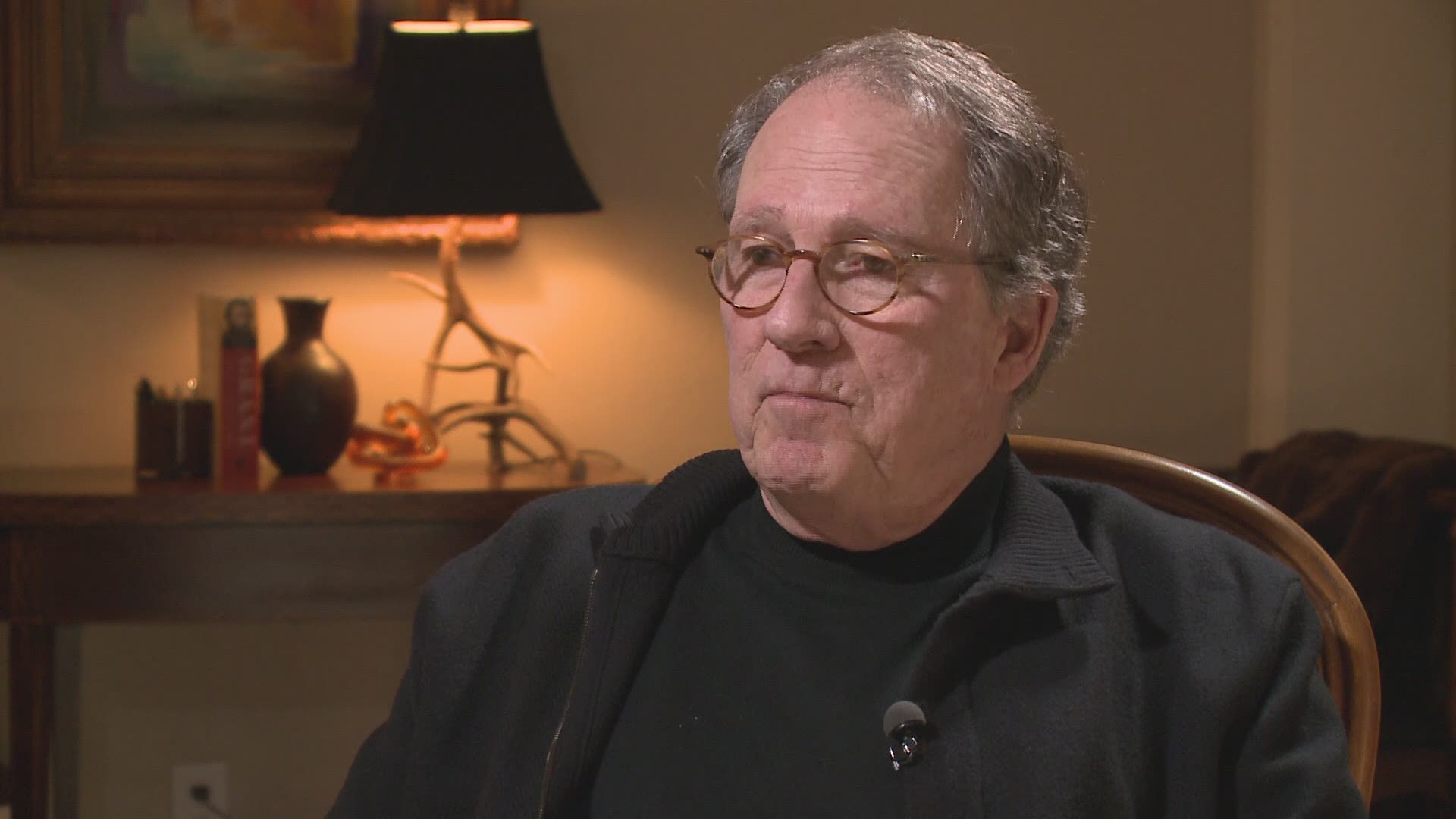

“If there was somebody, a classmate or teammate that felt like they weren't in a group of something, all Jake had to do was put his arm around that friend or student and say this guy is with me and he was immediately accepted,” said his father, Andy Agar.

Jake loved sports and was a great football player. He was even co-captain of the football team at Episcopal Collegiate during his junior and senior year of high school.

“He was a special kid,” his dad said.

Mr. Agar said the first sign they knew something was going on was when Jake and a couple of his friends were arrested in Allsopp Park in Little Rock for purchasing painkillers. It was Jake’s car so he went down to the police station.

“It just started going downhill from there. For the first time in my life and Jake’s, I saw that he was losing control,” his father added.

It was then during Jake’s junior year at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville that his parents sent him to a 28-day treatment facility in Nashville. But Jake got out and relapsed. He then entered a second treatment center but was sent home for purchasing drugs.

Addiction had a grip on Jake no matter how much his family tried to help him.

“His behavior was worse than it had ever been," Andy said. "He was totally out of his body. He was angry. He was visibly impaired. More so than I have ever seen him. He was belligerent. And these were characteristics of Jake that weren't ever there."

After a lot of resistance, Jake agreed to enter rehab for the third time. His father planned to pick him up from school in Fayetteville the next day. But on the night of December 4, 2013, Andy got a call that his son had died of a fentanyl overdose.

Jake Andrew Agar was just 21 years old.

“I was 12 hours too late," Andy said. "It was just dreadful. You’ll never forget that time. You'll never forget where you were. It’s one of those events that is branded into your mind. Your world goes pretty dark after that.”

Don’t be discouraged. There are people who are suffering from an addiction that turn their lives around, which brings us to our next “face.” The woman in this interview asked to remain anonymous. She began her story by telling us that her mother always made fun of her because she wanted to be a ballerina.

“I took a lot of dance classes and I danced until my senior year of high school,” she said. Her life was normal.

She had no idea where she wanted to go to college. But after a while, a lot of her friends were going to the University of Arkansas. So, she decided that’s where she wanted to go too.

“I got into a sorority. I moved into a dorm. Made a lot of friends,” she said. “I started drinking a lot and it started attracting the wrong types of people.”

She quickly found the wrong kind of friends and started trying new things. She found out she could sell her prescription pills and that attracted people who wanted to take advantage of that.

“Those people who were picking up the medication started to become my friends and they weren't very good people,” she added.

After going to college and then moving back home she started getting involved with harder drugs.

“I felt like I wasn't good enough. I felt like I couldn't make it. I couldn't even get a job. This isn't worth it. And so I started doing heroin,” she said.

She first tried smoking it off of some foil, but she didn’t like it.

“It tasted bad so somebody had suggested that I shoot it with a needle and I thought that was extremely disgusting.” But a lot of people suggested that it was the best high that you can get so she tried it. “And that is when I got addicted,” she said.

She began to chase the euphoric yet dangerous feeling of a heroin high. That chase eventually led her to an overdose.

Paramedics thought she was dead. They attempted to get ready to put her in a body bag, but she woke up.

“And they said the person who was on this stretcher yesterday had died from a heroin overdose. And they assumed that is what I had been doing and they thought it was too late,” she added.

This young woman didn’t really know what was going on, but when she got to the hospital and started feeling better, that’s when she knew she wanted to stop.

“This is embarrassing," she said. "All these people now know that I am doing this. And I don't want to do this anymore.”

She didn’t stay sober the first two times she tried, but she kept doing the work. “This person told me to call her every single day and I did. Even though I was getting messed up it was like giving me that responsibility of knowing that, ‘Hey, I hope you realize you’re getting messed up again. You’re doing this again,’” she said.

This young woman has now been sober since September 18, 2015. She can only worry about it one day at a time. “I can’t think about how I might want to relapse next week. I just think about today.”

The Problem

CALLER: She’s overdosing on Heroin right now.

DISPATCH: Are you with her right now?

CALLER: *Inaudible*

DISPATCH: Okay, how old is she? Is she awake?

CALLER: No, she’s not.

DISPATCH: Breathing?

CALLER: Barely.

ANOTHER CALL:

CALLER: There’s a guy slumped over here inside of his truck. He got syringes on the passenger side.

DISPATCH: Okay. Are you still there?

CALLER: Yes.

DISPATCH: Okay, so he’s slumped over in the truck and he has syringes in there?

CALLER: Uh-huh.

DISPATCH: Okay.

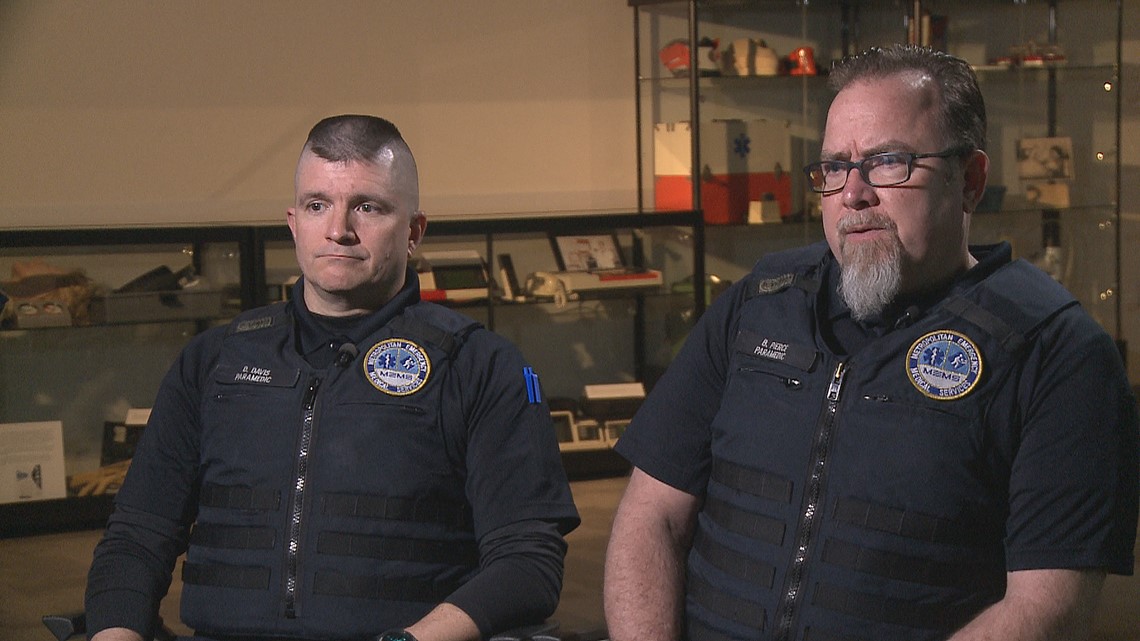

“I didn't think it was that bad. You kind of hear stories and you kind of have a picture of what a heroin addict looks like but then you get out there and realize it’s not what you thought,” said Byron Pierce.

He has been a paramedic for a little over a year, but he’s been with Emergency Medical Services for about three years. It's a problem we usually only hear about, but for first responders, it's an epidemic they witness first hand every single day.

“It’s your mom, it's kids, it's a couple 17-year-old girls who look like they just got off the cheerleading team, it's a 31-year-old hipster. It kind of shocks you a bit,” he added.

According to Metropolitan Emergency Medical Services (MEMS) in Little Rock, the number of overdose calls where Narcan was administered has more than tripled in the past four years.

Dwayne Davis has been a paramedic with MEMS for five years, but he’s been in emergency medicine for 24 years. He said heroin seems to be the primary opiate choice. “We get pills every once in a while, but usually those are a lot less common.”

Some of those calls are from repeat victims. It is the deadly cycle that addiction traps them in.

“You try and have a come to Jesus moment with them," Pierce said. "Sometimes you’re hoping they’re responsive and they are hearing you because they were just circling the bucket and you brought them back to life. And it might be an opportune time, but no, you’ll be back. And that's kind of disappointing, sure."

The number of overdose deaths in the United States is skyrocketing. In 2016, 64,000 people died of a drug overdose. More than 400 of them were right here in the state of Arkansas.

Arkansas’s Attorney General Leslie Rutledge said the numbers are astounding, but it is also unbelievable the number of lives we lose every single year. And we lose people not just because they have passed away and overdosed, but because they're no longer able to function in society.

“They have [been] absolutely crippled by their own addictions,” she said.

In Tennessee, drug overdose deaths have hit an all-time high. The state has seen a significant increase in overdose deaths largely due to the growing use of dangerous synthetic opioids.

According to Stan Jones, a special agent with the DEA, the region is being saturated.

“I don’t know of any place where it is getting better. I would like to think so but we see areas and communities where it is getting worse,” he said.

Jones was a police officer for 12 and a half years before joining the DEA in 1998. He’s been in Nashville, Tennessee for the past 10 years.

Jones told us that in his three decades in law enforcement, the opioid epidemic is unlike anything he has ever seen.

“We are seeing teenagers and middle school age of young people who are not only becoming addicted but who are dying,” he told them. The DEA is seeing an increase in dangerous synthetic opioids like fentanyl being shipped into the United States from Mexico and China in mass quantities.

Between two and three milligrams can be the difference between getting high or overdosing and dying. Fentanyl on the streets is a major concern, but Jones said this epidemic started largely due to overprescribing by pain clinics.

“We have gotten into this trend of trying to satisfy patients and eliminate pain or try and reduce that pain. And that is done with the prescribing of narcotics,” he said. “Unfortunately, we have a pendulum of where its turned into overprescribing and excessive prescribing.”

According to the CDC, Arkansas has the second highest opioid prescription rate in the country with 114.6 prescriptions written for every 100 residents in the state. That’s the equivalent of 250 million opioids prescribed for three million people in one year. Rutledge said this is why we have seen this increase in the epidemic due to the sheer volume of prescriptions available and the accessibility of young people with addictions to acquire them.

These addictions are resulting in scenes that were only seen in movies. It takes one life being saved and getting a second chance to make a difference.

“You’re giving someone another chance. What they do with that chance is their responsibility,” said Davis.

The Fight for a Solution

It’s a typical day in the vehicle of Independence County Sheriff Shawn Stephens. He, too, knows first-hand what it is like to see an overdose call in action.

“You look at them and they are the same age as your children your family. Your nieces. Nephews. And it’s heartbreaking,” he said. The heartbreak is the tragic reality for Stephens. He has been sheriff for a little over a year now, and since becoming sheriff, he’s seen an increase in the number of overdose calls. The sheriff’s office sometimes has four calls in one week.

In April 2017, the Independence County Sheriff's Office became the first in the state to receive the opioid antidote called Narcan. So far, deputies have saved eight lives. Two of those saved lives were thanks to Sheriff Stephens.

“I think the last time I looked I was the only one in the state that has done that,” he said.

Alisa and Scott Lancaster were the main push to get Narcan into the hands of first responders in Independence County.

Their daughter, Chelsea, died at the age of 26 from an overdose after taking a mix of prescriptions medications on January 27, 2017. Her death was the catalyst for their mission.

“It feels like maybe you have a purpose in life that you are doing something to prevent a tragedy and prevent another family having to go through it,” said Alisa.

After her death, the parents were devastated and thought they were on an island in dealing with this but soon found out the problem is bigger than they could fathom. “It is a tremendously prevalent problem and it has got to be addressed,” said Scott.

For the past year, Arkansas's drug director Kirk Lane has been working with the Attorney General's Office and several state agencies on securing grants to get Narcan into the hands of more law enforcement agencies.

“I think we have about 450 kits out statewide and I think in three months we will have two to three thousand kits out there,” said Lane. The Arkansas Alcohol and Drug Abuse Coordinating Council within the Department of Human Services have identified eight counties for 2018 and the agency intends to identify eight counties each year for the next five years.

Since the state began keeping track in 2016, law enforcement armed with Narcan have saved more than 60 lives (as of March 2, 2018). Lane expects to see the number of people saved by Narcan climb.

“It's a shocking number because of what is going on but I think it's a good number because it may turn mortality rate that we are seeing on overdose around,” he added.

Sheriff Stephens said while this is part of the fix, there are still some other things that need to happen. Progress has been made in the fight for a solution, but more needs to be done to turn this crisis around.

Celebrating Recovery

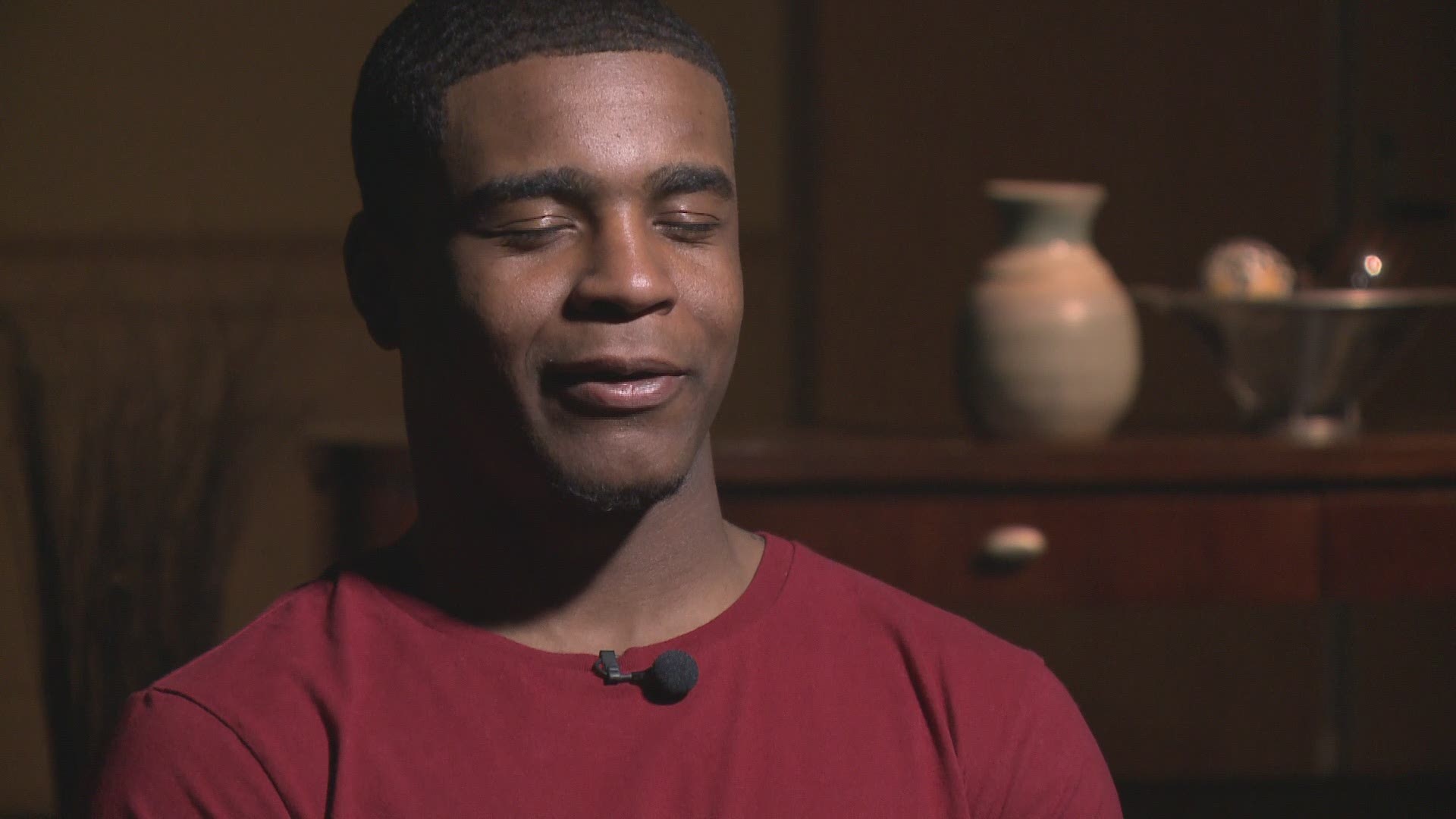

It would seem like 23-year-old Braylan Campbell has his life together. He is a college student at Texas Tech University, he's surrounded by friends and he is making good grades. But just a few years ago that Braylan’s life wasn’t so great.

He was on a dark path. He was arrested more than 20 times for drugs and alcohol.

The Little Rock native began drinking and using drugs at the age of 14. He was on a downward spiral at such a young age. And that downward spiral led him to addiction.

“I thought it was fun at the time but in reality, what I was doing was creating an addiction for myself. That I would later have to face in my life,” he told us.

It was a path of destruction for both young men. This path eventually led them both to Lubbock, Texas where Texas Tech has a collegiate recovery program.

Once a person gets into recovery they are looking for a purpose and a mission in life. They are looking for a second chance and universities can be those places.

Dr. George Comiskey is the Director of External Relations for the Center for Collegiate Recovery Communities at Texas Tech. The program has been in place for over 30 years. It gives students in recovery the support they need to succeed in college.

“The dean was very supportive of us being a place for people to land and have a second chance,” said Dr. Comiskey. “And they knew that many of these students would come with maybe a GED maybe having an attempt at college and crash and burn. Which is what addiction does to people. So, let’s give them a second chance. Let’s give them a fresh start and prove themselves.”

The participants have weekly recovery meetings, but the program is so much more than that. It’s on-campus housing, it’s a safe space where students can study and hang out. The program currently has 120 students who are all on scholarships thanks in majority to private donors.

“If they are struggling with their GPA then that allows us to override that because they are a person on scholarship and the scholarship is for them being a person of recovery,” said Comiskey.

It is considered the gold standard of collegiate recovery programs. Colleges and universities across the country look to Texas Tech to start programs of their own. It was the model used to get the Razorback Recovery Community at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville. Three years ago, the school created an environment for students in recovery to receive support. Alcohol and Drug Specialist, Dr. Asher Morgan, said the program is currently serving only about two to three students, but while it is small there is room for growth.

“It's the same with any program you want to see get started. It’s staff. It’s resources. It’s money. We have a dedicated space. The space is awesome and just getting out there and letting them know it is there," Morgan said. "You don’t have to worry about stigma, you don’t have to worry about shame and these people are here and they will take you just as you are.”

And the students agree with Morgan.

“I think we have an opportunity to really lead the state and really address the issue head-on,” said Trevor Villines. He is with the university’s Student Government Association. Villines is working with the university and state leaders to raise funding and awareness to get a more enhanced recovery program, like the one at Texas Tech, for Fayetteville.

The conversation is just now starting and meetings are just now taking place. “In the long term of things, we can look back and say, ‘Hey we got to be a part of this. We got to help start the conversation,’” said Villines.

“I feel confident that when we have the information that indicates. And I feel confident we will, that this is impactful for our community that we will have the support of our stakeholders to continue with that,” said Monica Holland, Associate Dean of Students for the University of Arkansas.

These collegiate recovery programs are already changing the lives of so many like Braylan Campbell. It has given him a fresh start and a fresh future.

“I pretty much thought I was destined to continue the same cycle. And this broke it. And I’m grateful for that,” he said.

The Why

You’ve read and seen stories of loss and recovery. Stories about the problem, and the fight for a solution. But there is one story we haven’t shared with you:

On September 16, 2015, I lost my boyfriend to a heroin overdose. I was blindsided. I had no idea the hold Brock's addiction had on him or that it would take his life at the young age of 27.

You see, I too never thought I would ever be personally affected by this epidemic. I read the stories. My heart hurt for those families who lost someone they loved. But I never thought this would happen to me. So, that is why I share my story with you.

After two and a half years of keeping silent, the truth is I’m tired of the feeling of guilt, shame. I’m tired of the fear of judgement.

The reality is this epidemic knows no boundaries. It doesn't care if you're rich or poor, young or old. It doesn’t care if you live in a good neighborhood and your kids go to a great school. It doesn't care if you are a news anchor with a blossoming career who is planning your life with the man you love.

This disease affects us all in one way or another. And this is why I am so dedicated to this fight. This is why you have my commitment and the commitment of THV11 to continue to share these stories.

To raise awareness.

To educate.

To eliminate the stigma.

We are in this fight together.

The fight to save a generation.”

-Laura Monteverdi

Resources

A:

Arkansas Drug Takeback- www.artakeback.org

Arkansas Dept. of Human Services

B:

Banyan Treatment Center

Behavioral Health Services of Arkansas (Seven Challenges Program)

- Contact: Dori Haddock dhaddock@bradfordhealth.net

Bridgeway Hospital (Detox)

C:

Capstone Treatment Center

Collegiate Recovery programs

Counseling & Psychology Services

- Facebook Page

- Contact: J.G. Regnier- jgregnier@msn.com

H:

- Strengthen your detective skills as a parent. Search this teen's room for clues that might indicate drug or alcohol use.

K:

Kristin Agar (Interventionist) Kristin@kristinagar.com

N:

National Center on Drug Addiction & Substance Abuse (CASA)

National Council on Seniors Drug & Alcohol Rehab

New Vision-Unity Health Center (Detox)

O:

Oasis Renewal Center

P:

Palmetto Addiction Recovery Center

Partnership for Drug-Free Kids

R:

Recovery Centers of Arkansas

Rivendell Behavioral Health Services (Detox)

S:

Speakup About Drugs: (Our Vision. Know Drugs. No Overdoses.)

Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)