A historic neighborhood's fight for environmental justice

Ivy City residents' decades-long push to remove chemical plant from community

Ivy City is a Northeast neighborhood tied by its historic industrial past and its growing gentrified future.

Homeowners say they are stuck in the middle of an environmental morass of toxic air and pollutants.

And the working-class families who make up this tight-knit community say they have been working for years for a basic right – to breathe clean air.

A Love for Ivy City

"This picture is from back in the 60s. I knew everybody here – everybody knows my siblings. It was a nice neighborhood," Brenda Ingram said.

Ingram has lived in Ivy City her entire life. When the tight-knit community of Ivy City was developed in 1873, it was hailed as a slice of suburbia for African Americans.

The neighborhood was comprised of single-family homes and apartment buildings, nearby, a railyard, warehouses and a factory, which all still exist along with a very distinctive odor.

"How are they able to stay in here, stay in an historical Black community, and use these chemicals?" Empower DC's Sebrena Rhodes asked.

They – are National Engineering Products or NEP, a company that produces a sealant for the U.S. Navy. The Bethesda owned manufacturing plant is in a small non-descript building on a corner in Ivy City.

The plant uses chemicals like formaldehyde, ethylene chloride and acetonitrile, chemicals that can cause health problems, including cancer. For decades, residents have voiced concerns about what flows out of the vents of the small brick building into the air.

Brenda Ingram said, "I was just, like, in disbelief, that's a chemical plant!"

"When you lose your sense of smell, and everyone is complaining about the same thing, headaches, dizziness, feeling lethargic and having breathing issues," said Sebrena Rhodes.

Residents describe a pungent smell of tar on production days at National Engineering Products. When WUSA9 stopped by the facility in Ivy City, it was clear to see and smell their concerns.

EPA Tests For Pollutants

"The residents did the right thing by bringing it to our attention," said Adam Ortiz.

Ortiz is the Mid-Atlantic Region Administrator for the Environmental Protection Agency. He says the EPA, along with the District's Department of Energy and Environment, have tested the air in Ivy City for more than 100 compounds.

"It's more than their fair share. But, we haven't found anything that's an acute threat to public health," Ortiz said.

The EPA will begin collecting air samples of formaldehyde and more pollutants, which did not include in its initial testing. The agency hopes to finish gathering data in September.

Sebrena Rhodes said, "Why is it taking so long for someone to get fired up and say let's shut this place down!"

Bill to Remove "Grandfathered" Factory

Shutting down National Engineering Products isn't quite that simple.

You see, NEP started operating in the 1930s, long before zoning laws prohibited companies like these from operating in residential neighborhoods. And, certainly before federal law required air pollution certification.

National Engineering Products did not respond to WUSA9's request for an interview. But the company's president, Nicole Barksdale, did tell our news partners at the Washington Post back in April that "NEP has been cooperating with city and federal officials and has submitted an odor reduction plan."

"I'm hopeful and confident that it can be relocated without much trouble," said Councilmember Zachary Parker.

The Ward 5 councilmember has introduced the Environmental Justice Act which will hold companies accountable for polluting communities and violating environmental laws.

"No longer are we going to tolerate what has long been a pattern, what we call environmental racism, that we've allowed these types of pollutants to exit in Black and Brown communities," said Councilmember Parker.

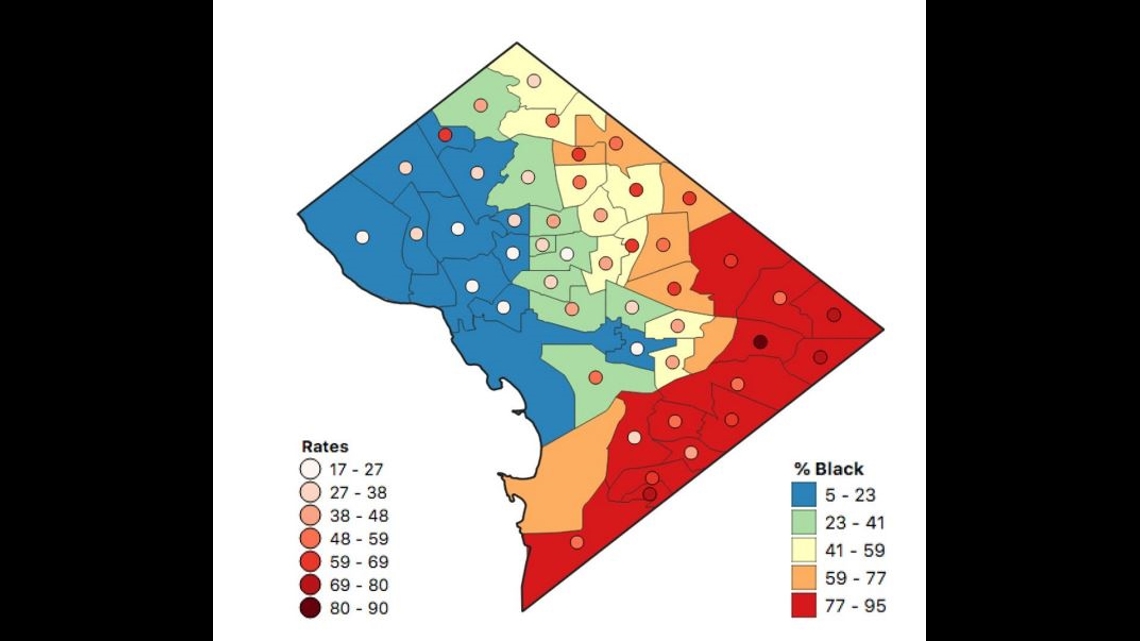

A map of the District of Columbia, created by Advancing Earth and Space Science, an international nonprofit, shows the percentage of Black residents in each neighborhood.

The shaded red area highlights predominately Black communities, including Ivy City in Northeast DC. According to AESS, the dots represent the rate of deaths attributable to air pollution.

"I feel like we're being cheated. Why do we have to have this in our neighborhood, you know," Brenda Ingram said.

Environmental Stressors Overload

The EPA's Adam Ortiz also pointed to a history of other environmental stressors impacting Ivy City residents.

He said, "New York Avenue is just a few blocks away. There's a rail switching yard that's used by CSX and Amtrak, vehicle maintenance yards for government and utilities. So, all of these things on top of each other in a working class community is a threat."

Meanwhile, Brenda Ingram sits on her screened in porch watching as change slowly comes to her neighborhood.

"Hey Ted," she said to a neighbor passing by.

She's hopeful that local lawmakers and federal officials will do something to help her and her neighbors breath easier.

WUSA9 IMPACT REPORTING

Part of what we do at WUSA9 is work to tell you stories that can make an impact.

New on Wednesday, we have an exclusive update on the neighborhood of Ivy City in Northeast, D.C.

A staffer of Councilmember Zachary Parker told WUSA9 that the Ward 5 councilmember will be introducing new legislation on Thursday.

The Ivy City Climate Resilience Hub Eminent Domain Authority Act of 2024 will give the mayor the authority to exercise eminent domain to remove National Engineering Products' (NEP) chemical factory from its Capitol Avenue, Northeast location.

NEP produces a sealant for the U.S. Navy that uses chemicals, like formaldehyde, that can cause health problems, even cancer.

For years, Ivy City residents have voiced concerns about what flows out of the vents of the small brick building into the air.