BALTIMORE, Md. -- Imagine having your hands shake so badly that you’re unable to drink a glass of water, to cut your food, or to comb your own hair.

About seven million Americans have inherited a genetic condition that gets progressively worse with age, leaving them with tremors that can spread from their hands to their voice and their head.

The University of Maryland Hospital is one of just a handful of facilities in the country where they’re offering an almost miraculous procedure that can stop tremors cold.

Tremor is an involuntary, rhythmic muscle contraction leading to shaking movements in one or more parts of the body. (Source: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke)

Matthew Jensen, a grandfather and drywall company owner, flew out from Denver to get help.

“This is a medium tremor,” he said holding his shaking hands up while sitting next to a glass of water at a picnic table next to Baltimore’s Inner Harbor. “If I was to try to get that to my mouth, I would spill all over.”

That was just what happened when he tried. The water spilled down his chin and across his shirt as his hands shook.

“I have to hold it with both hands and literally put my elbows down and get my mouth to it, in order to drink it,” Jensen said.

Jensen said he noticed his hands starting to shake uncontrollably when he was a teenager.

“The harder you concentrate, the worse it gets,” Jensen said.

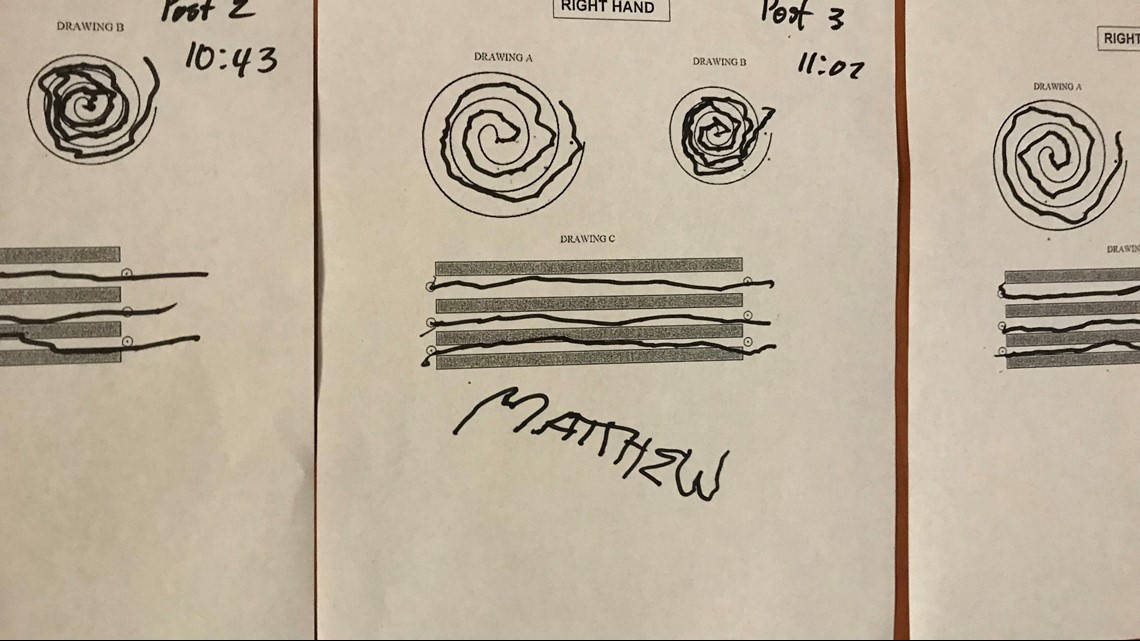

He has a hard time drawing a circle or writing his name. But he said the worst thing is other people’s reactions.

“When I crossed the border, border agents would always put me into secondary," Jensen said. "If I got pulled over, an officer would always think I was hiding something.”

The most common treatment for tremors is deep brain stimulation, which requires a surgeon to implant electrical probes in your brain and a pacemaker in your chest.

But Jensen has opted for a new, still-experimental treatment at the University of Maryland Medical Center in Baltimore. It’s called focused ultrasound.

The medical team strapped Jensen into an MRI and adjusted a helmet equipped with about 1,000 jets of acoustic energy around his head.

“We’re ready to sonicate,” said Dr. Howard Eisenberg, Chair of Neurosurgery at the University of Maryland Medical School, as he prepared to trigger the device.

Like a race where everyone wins, a thousand ultrasound beams must hit the exact same small spot deep inside the brain at exactly the same time.

“Thousands of beams come in, they focus on one spot, and they create a lesion,” said Charlene Aldrich, RN, the research coordinator for the project.

By creating a scar on a neural pathway in a section of the brain called the thalamus, doctors believe they’re blocking the misfiring electrical signals that are causing the tremors.

The focused ultrasound creates heat. The doctors start at the focused ultrasound at a low temperature, and then pull Jensen out and check his response, with exercises, a water bottle and a writing test.

If it seems to be having the right effect, they slowly increase the temperature to make sure the fix is permanent.

Jensen is awake throughout the whole procedure, so doctors can track his progress, which goes from shaky to almost rock steady.

“We had him write his name. And look at the tremor in the first one compared to this one,” said Paul Fishman, a professor of neurosurgery at the medical school, as he pointed to Jensen’s signature on sheets of paper taped the wall of a glassed-in room with a view of the MRI. The jagged edges of Jensen’s handwriting were slowly disappearing.

“Exciting. It’s really amazing,” said Jensen’s wife Bonnie, as she watched.

Doctors said ultrasound is less invasive than standard surgery. But if they over treat, they can leave the patient with the sensation of pins and needles or balance problems. In the worst case, bleeding and stroke are possible.

For Jensen, the three-hour procedure was a miracle.

“It feels awesome,” Jensen said drinking from a big plastic glass of water without spilling a drop.

It’s like the surgeons have given him his life back.

Jensen paid the tens of thousands of dollars for the focused ultrasound himself because few insurance companies will cover it yet.

So far, the FDA has only approved it for one side of the body, so Jensen had doctors fix the right arm, the one he shakes hands with.

Insightec, which makes the focused ultrasound device, is already looking at using it to treat Parkinson’s disease too.