SEATTLE — After weeks of social distancing to help curb the spread of coronavirus, it's only natural a few of us - okay, maybe a lot of us - might be thinking: What's the harm in visiting just one friend?

Well, according to researchers at the University of Washington, it could do quite a bit of harm and undo what our social distancing efforts have achieved.

Steven Goodreau, a UW anthropology professor, and Martina Morris, a UW professor of sociology and statistics, first launched the site appropriately titled "Can't I please just visit one friend?" in early April. The site shows how social distancing is affecting the spread of COVID-19 and what would happen if we all decided to visit just that one friend.

“There have been lots of discussions and articles about using social distancing to do things like ‘flatten the curve,’” said Goodreau. “We wanted to illustrate these principles at a community level, to help people visualize how even seemingly simple connections aren’t so simple.”

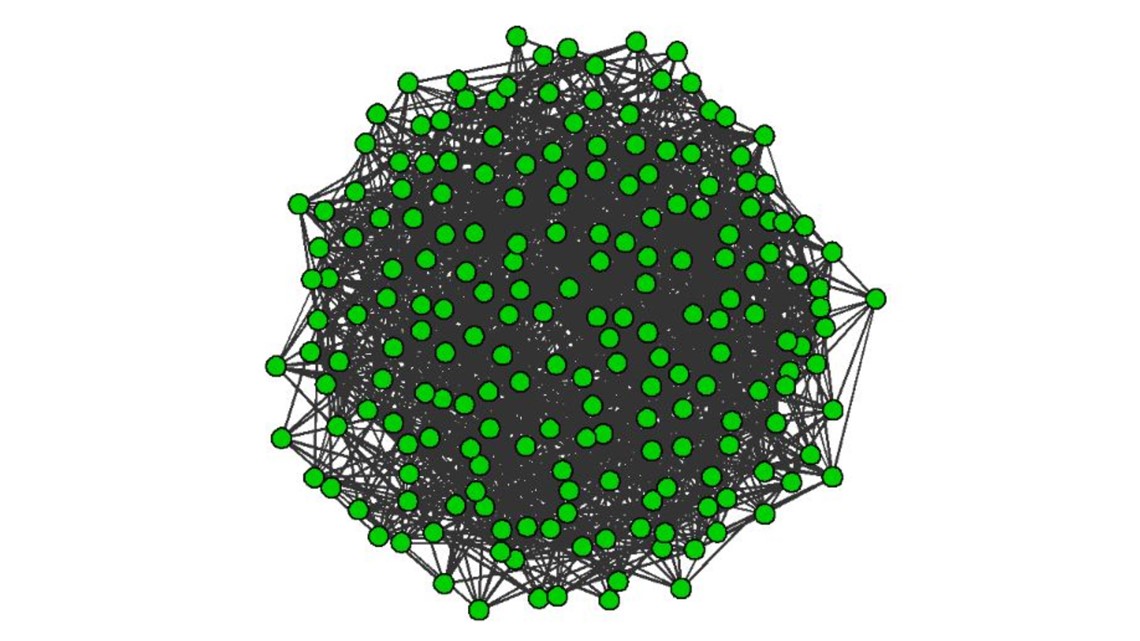

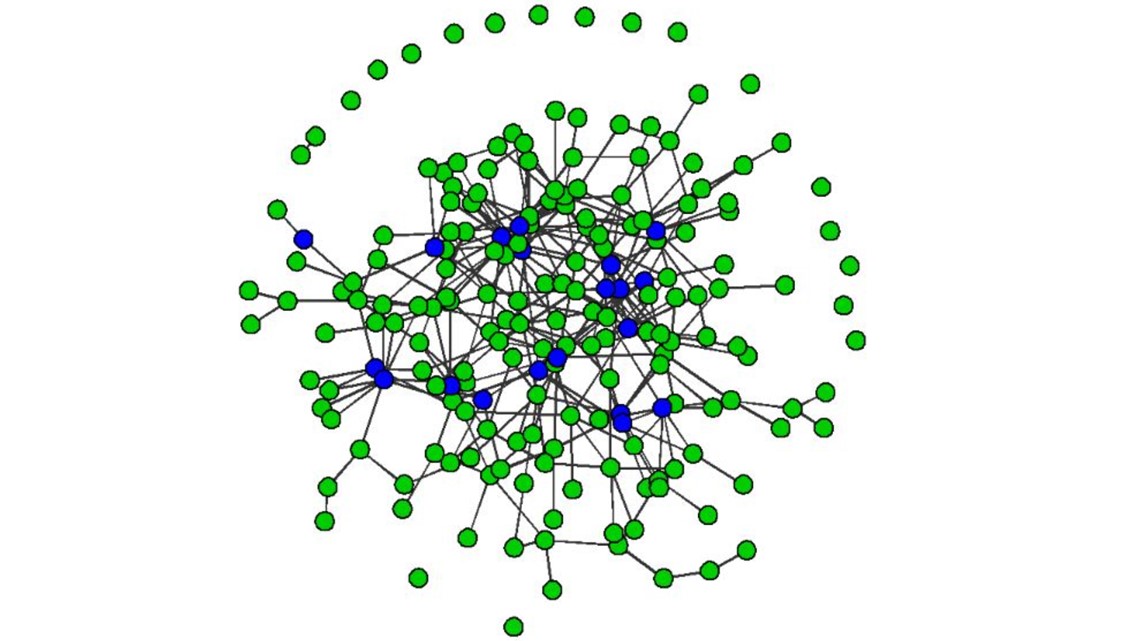

The diagram below shows human connections pre-COVID-19 and prior to social distancing. It represents 200 households and 15 ties per household.

The green dots represent individual households and the gray lines represent frequent, repeated interactions between any members of two households. As you can tell, the connections are numerous and it's hard to keep track.

In this network, every household can be reached from every other household along at least one path, so the largest cluster includes all 200 households or 100%.

For a new virus, this means it's pretty easy to spread across those ties.

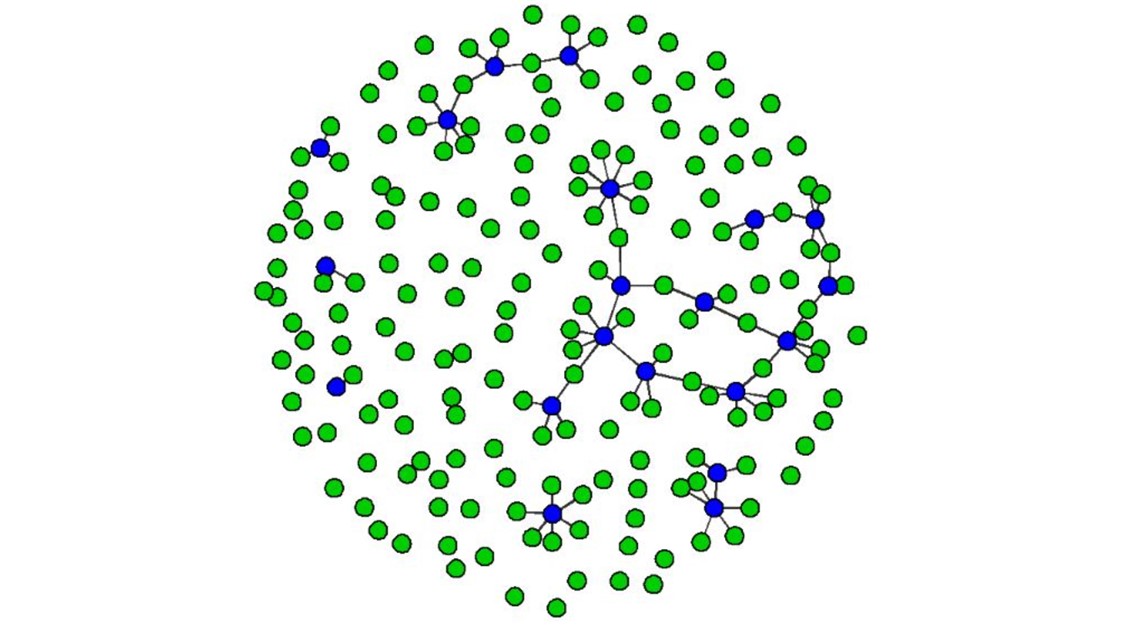

Now let's see what happens when social distancing is in place and the majority of people are following the stay-at-home order.

The diagram below shows most households are now isolated, but 10% of households, shown in blue, include a person with an essential job - such as a grocery store worker or medical staff.

According to Goodreau and Morris, these households still generate social connections that could potentially spread COVID-19, but the largest cluster created by these connections encompasses just 53 households or 26%. So, for the vast majority of households, there is no social connection to potentially expose them to the virus.

But, at this point, you've been cooped up for a few weeks and you're bored, so you decide to call a friend to see about hanging out in person.

The diagram below shows the situation if each household establishes one social connection with another household. The largest cluster, 142 households or 71%, are now reconnected in one large cluster. That's 2.7 times larger than the essential worker's network, according to the study.

Just one COVID-19 case in one of these households now has the chance to spread to nearly three-quarters of the families in this community, whether through direct or indirect social connections.

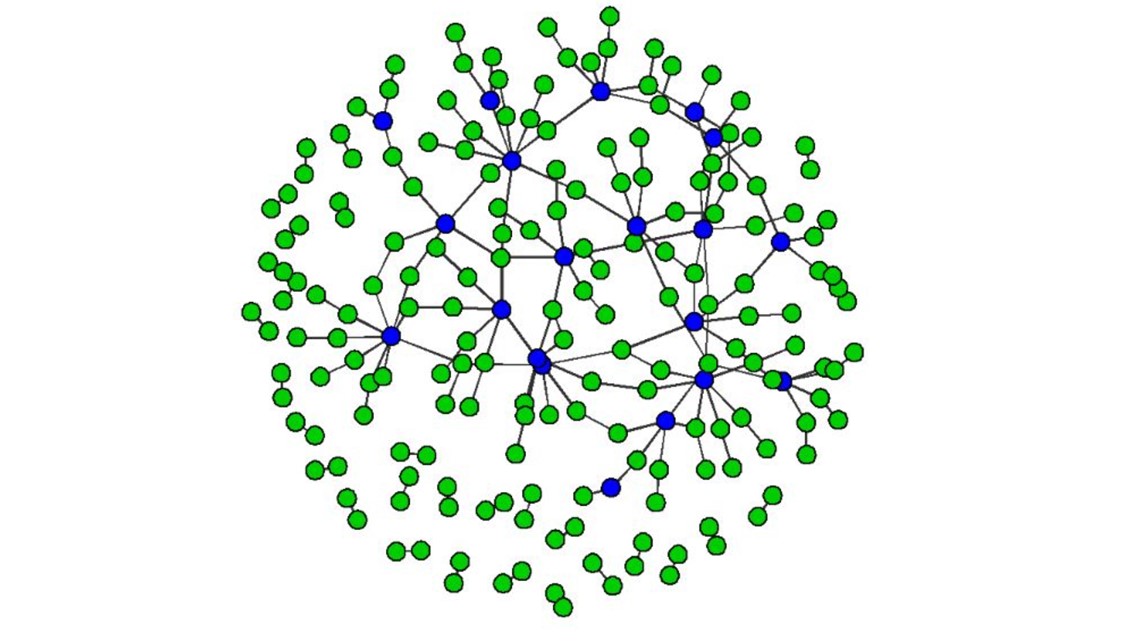

Now, the diagram above is assuming that each household only allows one social connection outside the home, but that's probably pretty difficult to pull off. For example, if you're a parent with two children, chances are if you let one child visit a friend, you'll have to let the other child do the same.

The below diagram shows what happens if an average of two people in each household decides to maintain an in-person social connection with one person from another household.

It's a much larger increase in connections. The largest cluster contains 181 households or 90.5%, which is 3.4 times larger than the essential worker network above. This means if you're part of that large cluster, your household can reach 90.5% of the households in your community and they can reach you.

The chance for the virus to spread amongst this community is far greater than if we keep to our own households.

Humans are social animals and reducing connectivity in social networks is hard, but researchers and doctors alike agree we must stay the course with social distancing to keep slowing the spread of the coronavirus.

“We purposefully keep this quite simple to get the basic idea across to people,” said Morris. “It shows why connections can spread more than we realize, and much more than our instincts might tell us.”