WASHINGTON — When you meet Tyrone Walker, it's like picking up a conversation with an old friend.

He's relaxed and calm -- which makes you feel like you can tell him your life story -- but instead, he tells his.

"I fired a gun that took somebody's life. That was the worst mistake of my life," Walker said, talking with his hands and watery eyes.

Walker grew up in the Shaw corridor of D.C. and recalls the smell of Wonder Bread rising at the nearby bakery, arcades and pool halls. He remembers heroin, PCP and crack cocaine coming into and out of his home.

He describes what life was like before he lost his 20s and his 30s to the inside of a cell.

“To be sentenced as a juvenile to 127 years to life, I couldn’t comprehend that; none of us could, so we walked around in this system numb," Walker said.

Walker got a second chance at life at age 44; when he was released on supervised probation after serving nearly 24 years 8 months and 15 days of his sentence.

Under a D.C. law called the Incarceration Reduction Amendment Act of 2016, or IRAA, violent offenders who committed their crimes while under the age of 18 --and have served 15 years of their sentence -- are allowed to petition for re-sentencing trial. But they have to prove they’ve rehabilitated.

Now D.C. Council is considering expanding that law to include anyone who committed a crime while under the age of 25.

Walker is one of 18 returning citizens who, proved his rehabilitation, and got a second chance under IRAA. Now he's doing it for IRAA 2.0 by testifying in support of B23-0127.

"Young people aren't fully developed all the way until their mid-twenties so we know from brain science from adolescent development research that young people are still developing and so this recognizes that," Marc Schindler, Executive Director of Justice Policy Institute, said.

"If someone committed even a serious crime as a young person, if they have successfully rehabilitated themselves over time and can demonstrate they are not a threat to public safety; they should be given an opportunity to show that," Schindler said.

Criminal justice advocacy groups contend that when these offenders, return to society in their late 30s and early 40s, they're not a threat to the public.

"It's important to realize that people generally age out of crime," Joshua Rovner, a senior advocacy associate at The Sentencing Project, explained. "What we're understanding about offending is that it drops precipitously following adolescence. Many people think of adolescence ending at age 18 but nothing really magical happens at age 18....the evidence of brain science really shows adolescence ends at about one's mid-20s."

D.C.'s topmost prosecutor, describes the bill as shortsighted at best, and dangerous at worst.

"We’re talking about individuals who were convicted of very serious violent offenses," U.S. Attorney of the District of Columbia Jessie Liu said. "So murder, sexual assault and sexual assault of children...in the current climate I’m very concerned about that."

In the city, 18 percent of offenders convicted of murder were either 23 or 24 at the time of the abuse, according to data from the D.C. Sentencing Commission. Twenty-three percent of those convicted of manslaughter were between 19-23 at the time.

If the new, expanded version of IRAA passes, 583 offenders would be eligible to apply for early release. Liu says she's concerned about recidivism.

"Our communities are safer when we do a better job of rehabilitating in our custody, Liu said. "The Council should not hastily pass this legislation but should instead gather data about how defendants released under the current version of the IRAA fare over time. The victims of these crimes and the community at large should not be jeopardized by the Council's rush to expand IRAA. The proposed legislation misses the mark."

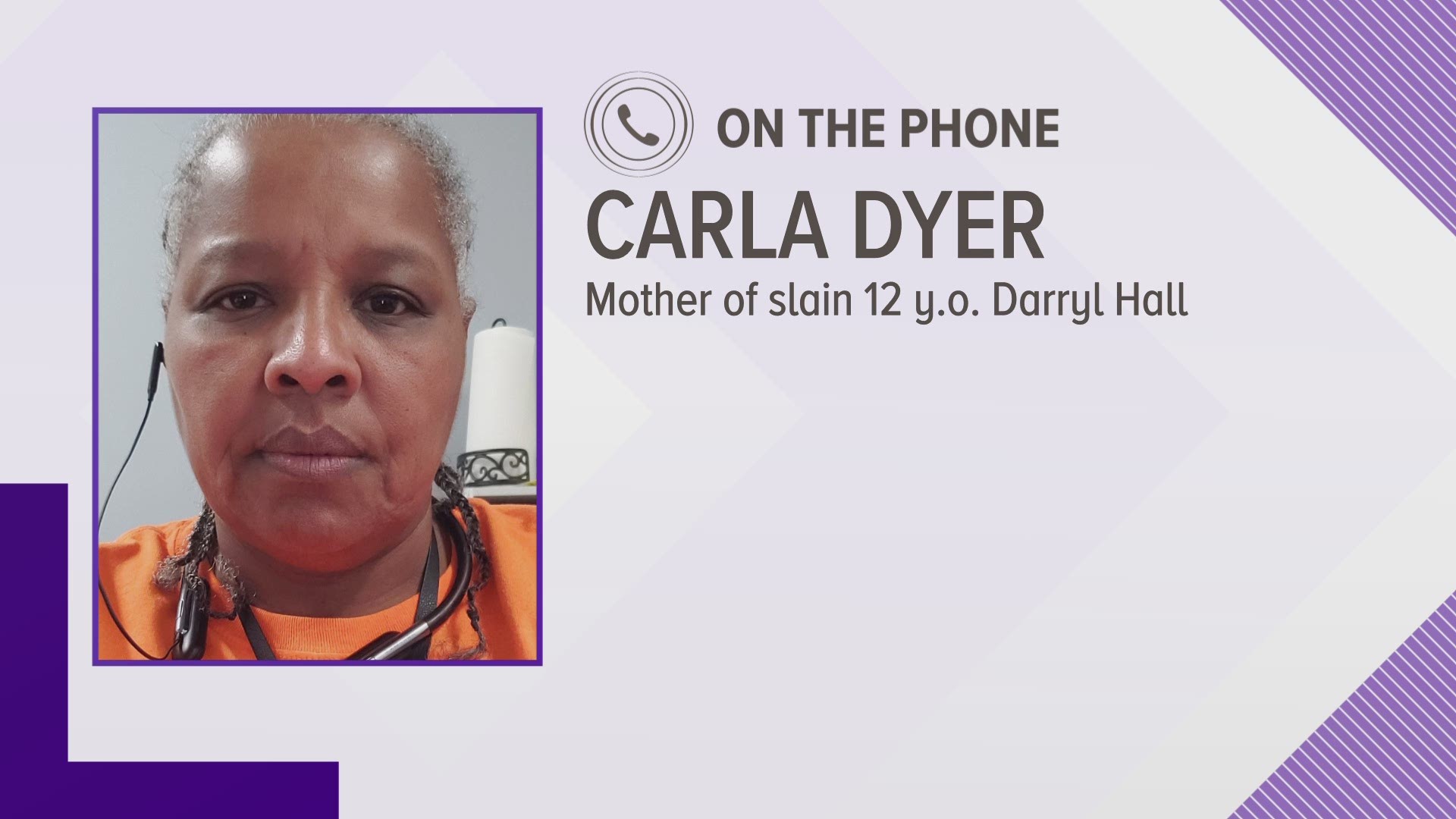

When she heard about D.C.Council's plan, Carla Dyer, mother of 12-year-old Darryl Hall who was shot and killed in 1997, was at a loss for words.

"That's really crazy, D.C.'s just going to have bodies everywhere," Dyer said. "That's not fair, that's not fair at all."

A 16 and 17-year-old were convicted in Hall's case, but under IRAA (2016)--the 17-year-old got out on early release. She says whoever came up with this bill didn't have her or her "baby boy" in mind.

"If somebody 25 or under does something to someone as heinous as they did to my son and they out in 15 years, they still could come out here and do whatever they want to someone else again," Dyer said. "They're going to continue doing it."

RELATED: MAP: 2019 Washington DC Homicides