30 years ago: DC's crack kingpin Rayful Edmond arrested at just 24. Here's how he built his empire

DC's biggest and most destructive drug dealer was sentenced to prison 30 years ago for the rest of his life, but now Edmond may be set free.

After nearly 30 years in prison, most of that time divided between maximum security and witness protection, Rayful Edmond III, the biggest drug dealer in the Washington, D.C.'s history, could be on his way back home.

Sometime in May, Edmond is expected in a U.S. District courtroom where he will try to convince a federal judge to let him go free with time served. Most D.C. murder sentences end a lot sooner than Edmond's 30 years in prison.

Here is the real surprise: The federal government supports the 54-year-old's bid to go free. Federal prosecutors and prison officials filed a motion to reduce his life sentences. It's a move that, observers said, is highly unlikely and rare.

The government is arguing that Edmond's assistance in breaking up other drug operations has been invaluable. They said he has led them to more than 100 drug dealers arrests, prosecutions and convictions.

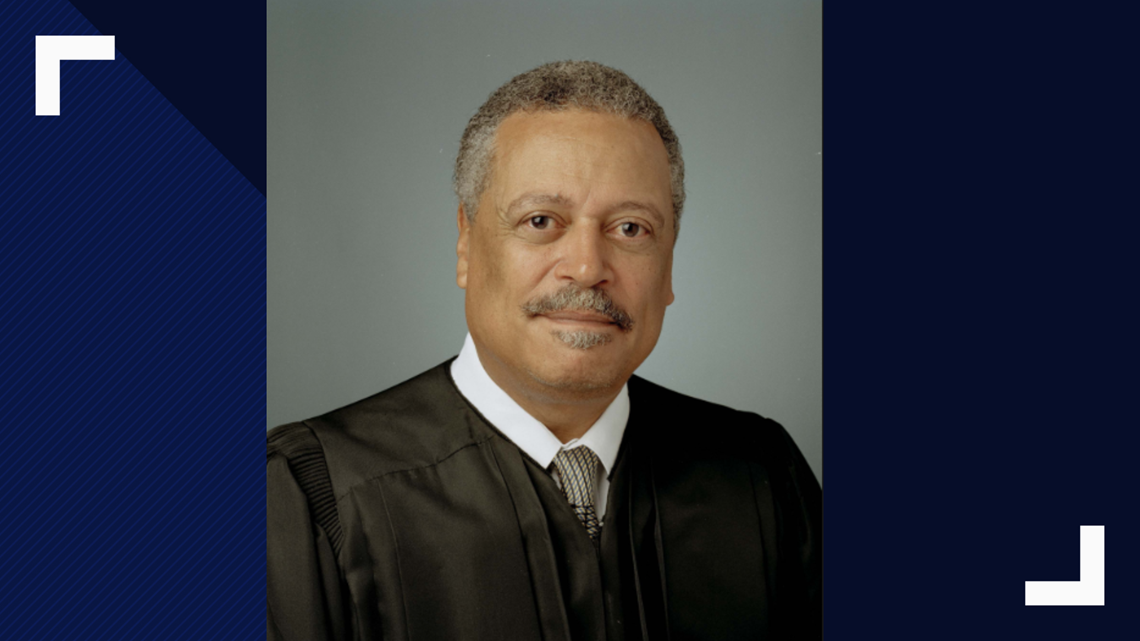

The case has been assigned to U.S. Court District Judge Emmet Sullivan.

Even though in the court motion the government doesn't explicitly ask for "time served," WUSA9 has learned that officials do believe Edmond should be allowed to go free.

Edmond's cooperation with federal agents is described as taking on many forms, ranging from assisting in the conviction of extremely violent individuals, to assisting in the investigation of ongoing narcotics trafficking to assisting in the institution of prison reforms. They characterize the defendant’s cooperation as both deep and wide.

If you go back to April 15, 1989, who could have predicted such an outcome?

Edmond's Rise To Crack Kingpin An empire at just 24 years old

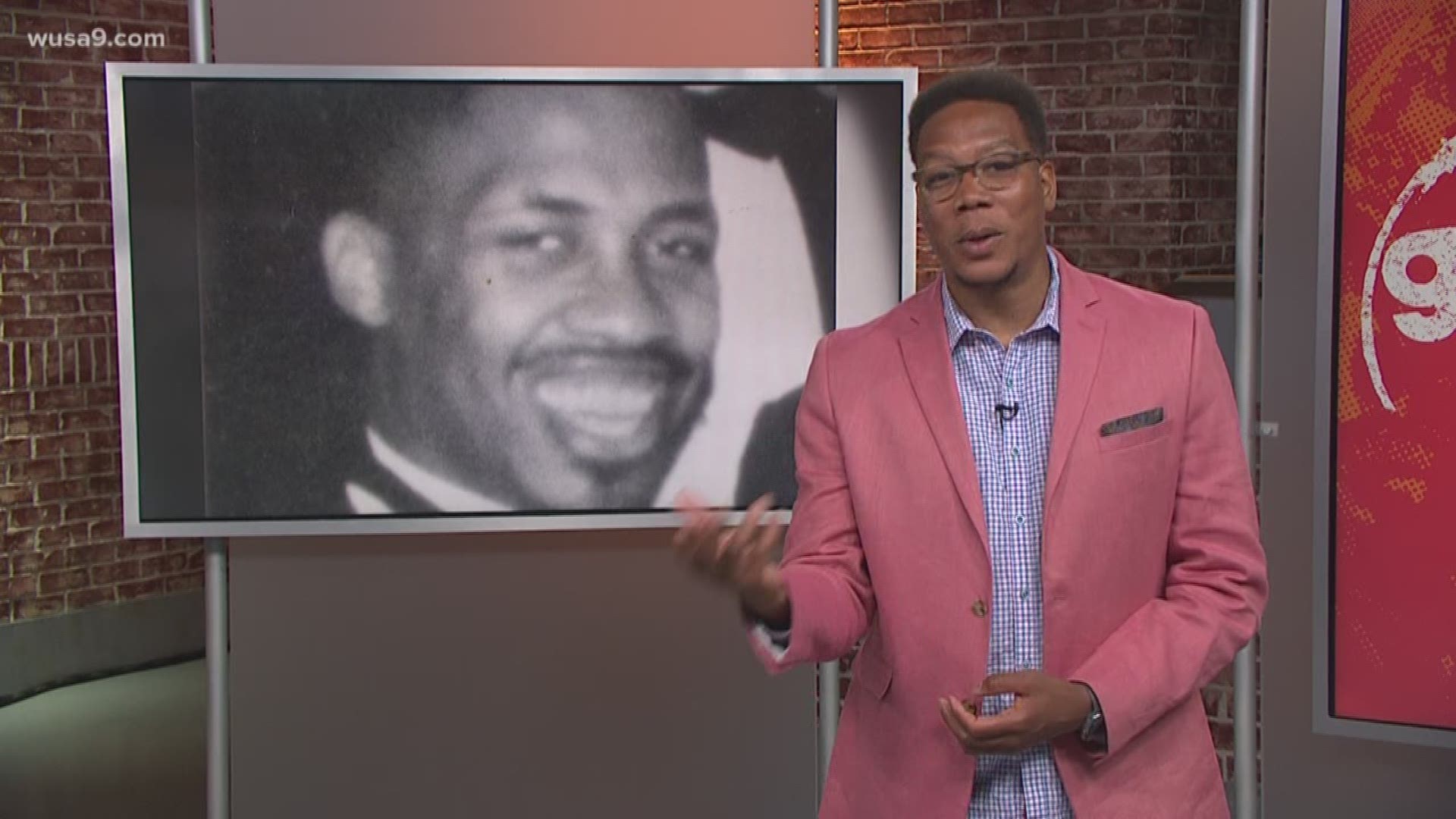

Edmond had become a street legend in but a few years. D.C.-based movie director Kirk Frazer would make a movie about him. Hip-hop artists invoked his name in their lyrics. Young street kids not even born when Edmond ruled the streets claim to be his offspring or made in his likeness.

Edmond, when he was arrested at age 24, had become D.C.'s biggest, most successful and feared crack-cocaine dealer. He was a D.C. native who grew up on M Street, NE. He was smart, a really good basketball player, charismatic with a quick laugh and constant ear-to-ear smile.

Like a lot of the young drug dealers around him, Edmond wasn't poor. His mother and his father had government jobs. But by age 9, he had been exposed to the drug life by his father, Rayful Edmond II. The drug business was equal opportunity; a chance to leap over the rest of the working class into a land of riches.

The people who got hooked on drugs were frowned upon, but the young drug dealers on the corners, the drug bosses and their lieutenants were often considered pillars of the neighborhood.

The influx of drug money into their neighborhoods bought groceries, fancy designer clothes, expensive cars and travel, team uniforms and the best seats at college, Bullets and Redskins games. Drug dealers had cash on hand day and night. They were the ATMs before there were ATMs.

The young drug dealers often had their choice of girlfriends, too. Many of them, like Edmond, left babies behind who had to be reared by young mothers and grandparents after the young father went off to prison. Edmond left two sons when he went away to prison on multiple life sentences.

By any measure as a young drug dealer, Edmond exceeded all expectations. By the time he was 22, investigators said he employed 150 people, many of them juveniles who worked the street corners as crack pushers or lookouts on guard for lurking plainclothes cops.

They planned escape routes down alleys and through boarded up row houses when cops jumped out of their vehicles. Depending on which federal investigator was telling the story, the Edmond drug organization was grossing $200 million per week or $300 million annually.

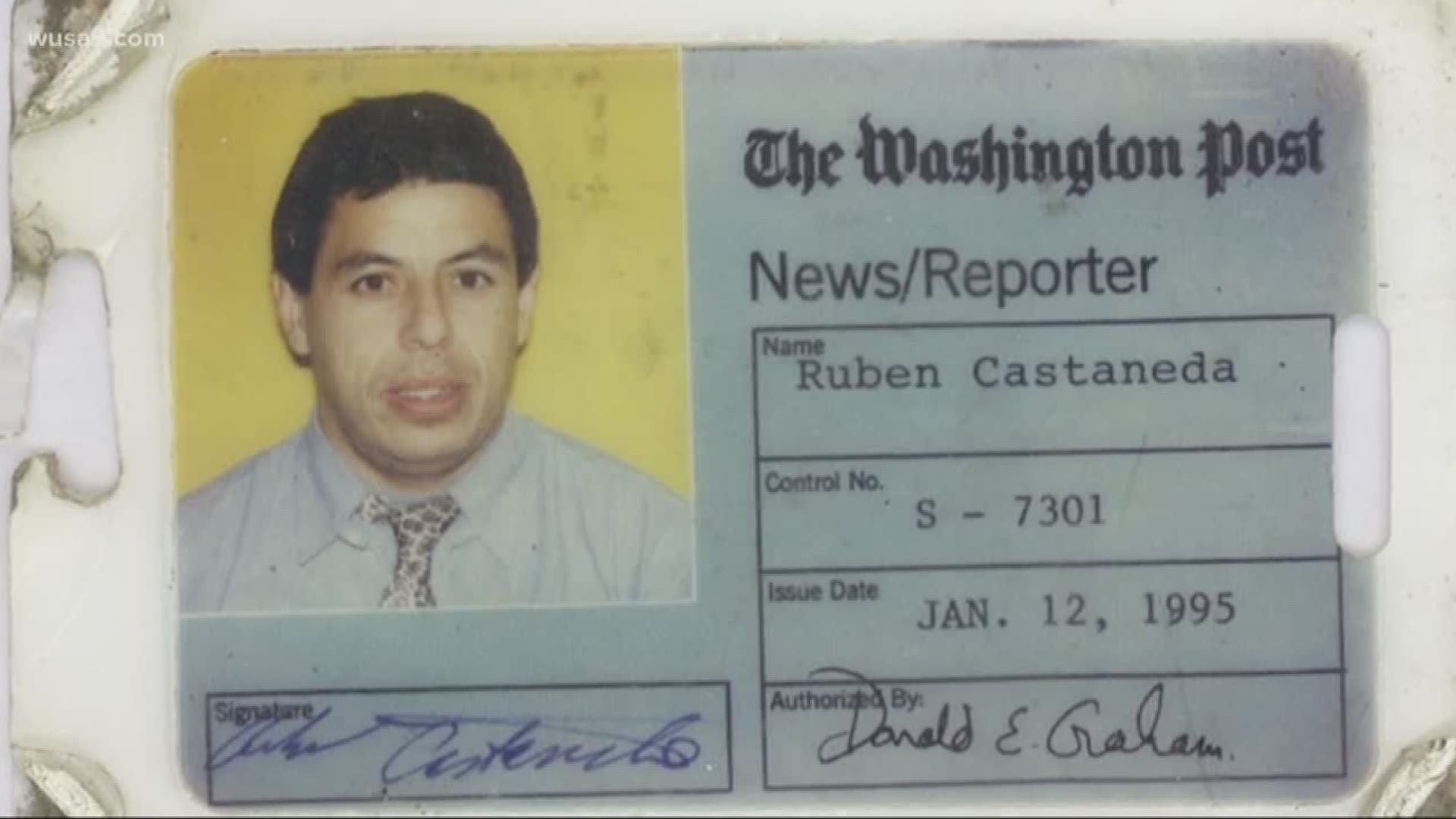

Rubin Castaneda was a Washington Post reporter assigned to cover the crack epidemic when he became hooked on crack. He describes his work at the time as a roller coaster.

"For me, as a reporter covering this was like being on a perpetual adrenaline rush," Castaneda said. "There was non-stop drug dealing, slingers on the street 24/7 and you had violence break out as young men and dealers fought for turf, so it was not safe to live on these blocks."

Castaneda, who wrote a book "S Street Rising" about his own drug involvement said Edmond wasn't the only big drug dealer in D.C. and his arrest had little impact on the city's bustling drug trade.

"There were probably dozens of Rayful Edmonds in terms of young men who ran blocks and sold a lot of drugs responsible for high levels of violence," Castaneda said.

The bulk of the crack and cocaine demand came from working stiffs of all colors, from the city and its suburbs. They started out as recreational users, moving to the cheaper crack from marijuana and PCP. Their vehicles crowded Hanover, Florida Avenue, Orleans and the Trinidad neighborhoods by day and night.

It was a very violent time, fueled by the crack epidemic and vicious turf bales. D.C. became known as "The Murder Capital." Edmond was never charged with murder, but he wasn't clean by any measure.

A drug business this big needed an army to protect the enterprise which eventually covered nearly a third of the District of Columbia. At least 30 homicides were tied to the Edmond organization.

Catching Rayful Police were unprepared, over-matched and caught in the middle

Lowell Duckett was a lieutenant in the D.C. Police Department's famed "Delta Unit." He said police in the beginning were no match for the crack and violence that came with it.

"Keeping it real: We were overwhelmed. When the crack epidemic hit, the D.C. Police Department wasn't ready for it," Duckett said. "We had to upgrade. We went from a revolver to a semi-automatic, and we had to go through the training process, which involved tactics."

An outsider might ask how did the Edmond's drug operation exist for roughly half a decade without drawing attention from local law enforcement?

An easy answer is that some D.C. police officers assigned to the Fifth District were childhood friends or associates of Edmond's, either looked the other way or, in one reported case, acted as body guards for Edmond's operation in northeast D.C.

At or near the top of the Edmond operation was his mother, an aunt, two sisters, a brother-in-law and close childhood friends, like Tony Lewis.

Edmond wasn't low key. He and his close associates were living large and in plain view from the beginning. They liked flashy clothes, jewelry and expensive cars. There were cash junkets to Atlantic City, Las Vegas and the west coast.

And Edmond could ball. He loved basketball and was often spotted at Georgetown Hoya games. His childhood friend, John Turner, was playing for coach John Thompson who eventually sat down with Edmond and asked him to stay away from the Hoya program and his star player Alonzo Mourning in particular. It's one of the most recounted moments in Edmond's story.

Edmond obliged, but his continued friendship with Turner saw the 6-foot-8-inch player eventually leave the Hoya program.

Edmond's big drug supplier had been a Los Angeles dealer with connections to Colombian drug cartels. The beginning of the end of his empire came when his D.C. mules were arrested while picking up drugs in Los Angeles.

Then, on April 15, 1989, a 43-count indictment was issued and Edmond was arrested with 28 others. Their trials were held under the tightest security by scores of deputy U.S. Marshals. The defendants were separated from the rest of the public by bullet-proof plexiglass.

Edmond, Lewis and others were not held in the D.C. jail like most federal prisoners. They were locked up miles away at the Quantico Marine Base and flown into D.C. every morning before trial.

One-hundred witnesses testified. Many of them were former Edmond gang members who turned state witnesses.

In the end, Edmond was convicted and sentenced two life-terms in prison. And, that should have been the end of his drug running days, but, D.C.'s crack kingpin was hardly ready for retirement.

He was sentenced to a maximum security prison in Lewisburg, Pa. Within days of his arrival, the now infamous D.C. drug dealer was introduced to a fellow inmate, Osvaldo Trujillo-Blanco "Chiqui," a convicted drug felon. It turns out that Chiqui was cocaine royalty and son of Griselda Trujillo-Blanco, also known as the godmother of the Colombian drug underworld and founding member of the notorious Medellin drug cartel.

Chiqui was eventually released from prison to return to Colombia and his horse ranch. 60 Minutes reports that's when Edmond's drug operation from behind prison walls took off.

The D.C. kingpin was eventually caught again and given another 30 years in prison. That was when Edmond turned "snitch," agreeing to help the government identify as many as 100 other drug dealers in exchange for his mother's release from prison. She had been serving a 24-year sentence.

Early Release? Despite the crimes, support has grown for Edmond's early release from prison

Edmond is currently 54 years old. Only he and Tony Lewis remain behind bars. Lewis' son, Tony Lewis Jr., won't comment on whether Edmond should be released for time served and his snitching for authorities.

The younger Lewis is married with two children and visits his father often in the federal prison in Cumberland, Md. He said that his father, who is the same age as Edmond, is a model prisoner and often counsels younger inmates. Lewis Jr. said at this point, it would take a presidential pardon for his father to be released.

Edmond, on the other hand, has federal prosecutors in his corner. What he needs is to convince Judge Sullivan. A D.C. native and Howard University undergrad and law school graduate, Sullivan has a reputation as a no-nonsense, tough judge. He once threatened to send President Donald Trump's former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn to prison.

Sullivan has ordered the government and D.C.'s elected attorney general to spell out how he'll hear from victims of Edmond's drug organization. The government has asked for an extension to prepare a response.

The people that we've talked to in person and those on social media are mixed in their opinions. Retired Lieutenant Duckett tells me at first he couldn't believe that the government wants to release the infamous drug dealer, but has since reached another conclusion in looking closer at the case.

"There's still redemption to be done and that's going to be when he gets out. We have to wait and see on that. My prayer is that he's true to his word and he's going to continue to do the good works that he's done while he was incarcerated," Duckett said.

Olivia Chase, a recovering drug addict, said she lost everything on the streets during the Edmond reign, including a stepson. Today, she is an activist and raising a grandson. She recalled how crack made her insane but she does believe Edmond should be released.

"Of course, many lives have been affected, many people have lost a lot of things, including their own lives. But, I think if he has an opportunity, as I had, to recover from that lifestyle then he should be given an opportunity to recover from a hopeless malady," Chase said.

A retired parole officer, who declined to be interviewed on camera, said nine young men in his caseload were eventually killed. He said everyone had been employed by Edmond and he blames him for their deaths. He opposes his release.

On social media, scores of people are coming down on both sides of the argument. Some said Edmond could be a positive influence, like other returning citizens.

Paul Winestock, a childhood friend and later Edmund associate, served 23 years in prison when his drug organization was brought down. He currently mentors juvenile offenders and employs returning citizens in several legitimate businesses that he owns.

Winestock said Edmond and his former lieutenant, Tony Lewis, should be given credit for how they've served some 30 years in prison and should be allowed to make amends in the communities they once helped destroy.

Former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder was the top federal prosecutor in Washington, D.C. when Edmond was taken down. Holder declined to comment on the government's recent motion for WUSA9's story.

Judge Sullivan has made clear he wants to hear from Edmond and from victims, too. Sullivan could deny the government's request. He could reduce Edmond's sentence to time served, or he could impose a new sentence of less than life, making Edmund eligible for parole at some in the future.