WASHINGTON — Lucille Leach sat down on a bench in Washington D.C.’s Anacostia Park with a heavy heart. Weighed down by six years of questions.

“I don't know who killed my son,” she sighed. “But whoever killed my son, they are not living life for good."

A necklace dangled around her neck with a picture of her son, Antonio Leach in a locket. A son she keeps close to her heart.

“I talk to him every morning and I go see him every month,” she smiled.

What happened to Lucille’s son has become a story that lives online in a series of music and commentary videos. Millions of people have seen the last days of Antonio’s life play out in a story that is too familiar in D.C.

Lucille tries her best to explain what happened from her point of view. It was 2016 and Antonio got caught in a back-and-forth war of words with someone Lucille wouldn’t name. A rival from another DC neighborhood that Antonio had a conflict with.

“My son didn't even rap until this person put out a song on my son,” Lucille said. “They called my son a snitch.”

That is when the feud escalated. Lucille believes Antonio felt pressure to respond to his rival’s music video. So Antonio made one.

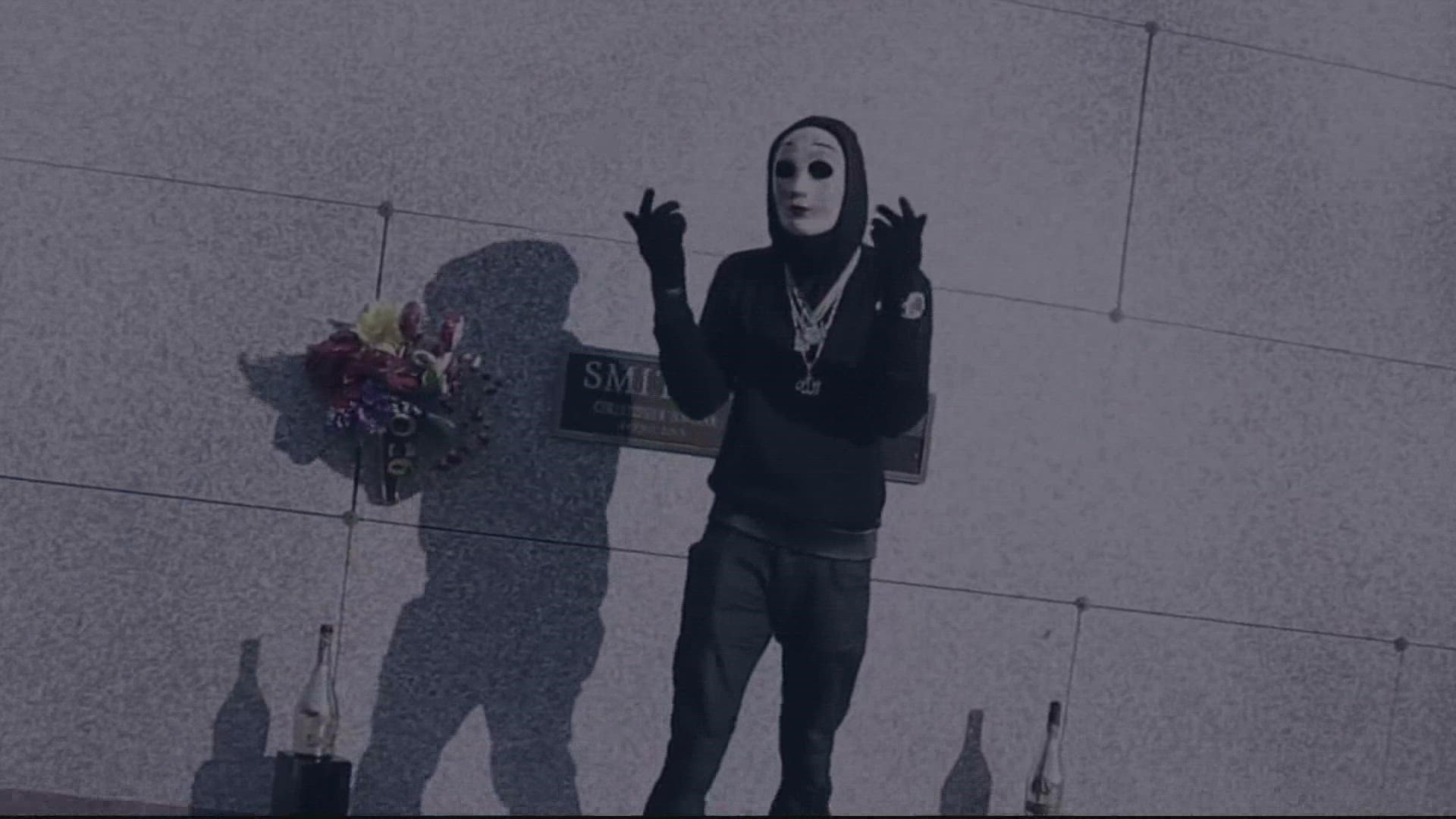

Using the name OGMan Man, Antonio shot a music video called “Truth.” It was a shocking display of insults and threats to his rivals. It even featured him performing near the grave of that rival’s friend.

“I told him, please don't do it, but he had already done it,” Lucille said. “But when he did his, it was seen by millions.”

“After that video came out, I want to say it was two weeks after, they killed my son.”

Lucille said she got the call Antonio had been called to a cookout nearby his home. That’s when someone shot him to death. Six years later, there are no leads and no witnesses -- just a cold case that’s left a D.C. mother empty.

“When this person killed my son, they took a part of me away,” she said as she stared at his picture on her locket.

Unfortunately, the story of Antonio Leach isn’t rare in D.C.

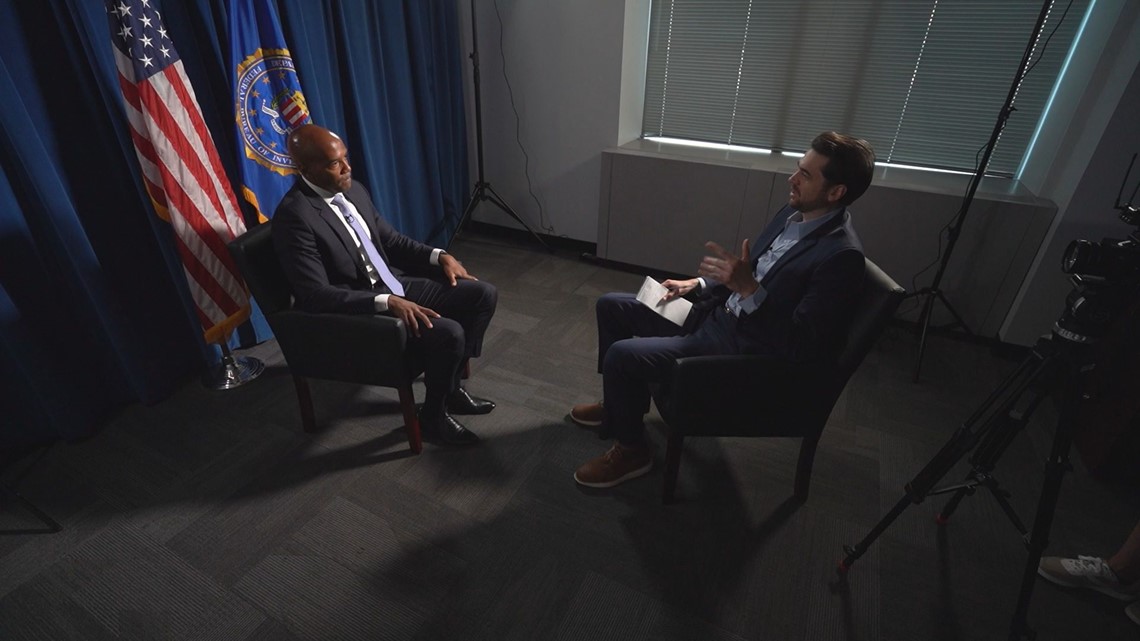

“Violent crimes are occurring because of slights that are being traded back and forth between rap groups or crews,” said Wayne Jacobs, Special Agent in Charge of D.C.’s FBI Field Office.

Jacobs' office tracks D.C.’s neighborhood crew violence. The office works with DC Police to curb it and solve violent crimes.

“It's not necessarily about the music,” Jacobs said. “But it's people using the music as a platform to talk about things that they're either doing, or issues or disputes that they're having with others.”

That theory is backed up by a 2021 report from the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform. The analysis of D.C. gun violence found:

“Exacerbating the social media incited shootings are music videos that promote certain neighborhoods or cliques that also “dis” other crews or individuals, sparking a series of comments and competing videos that escalate into shootings.”

We dug though D.C.’s homicide court files and found further evidence of the trend.

Specifically we looked at three of D.C.’s high-profile killings of children bystanders, 10-year-old Makiyah Wilson, 11-year-old Davon McNeal, and 6-year-old Nyiah Courtney. Inside each case's evidence files were YouTube links to music videos showing some of the suspects threatening violence or disrespecting a rival neighborhood.

A Metropolitan Police Department spokesman did not want to go on camera, but did acknowledge this phenomenon does exist. Detectives use the videos to show evidence of a rivalry that spilled over into violence that in these cases cut down the lives of innocent children.

That’s the view of law enforcement.

In the music community, there is a different take. D.C. hip-hop artist Young E Class calls the connection between videos and violence nonsense.

“These issues [have] been going on since before rap,” he said. “hip-hop might be 40 or 50 years old and these streets situations going on long before that.”

E is no stranger to the streets of D.C. or neighborhood conflicts. He served time in prison for a crime committed in his youth. Since getting out, he’s worked on his music career and also trying to stop the violent cycle that he once was caught up in.

“Even if you just take the music away, there are still issues,” he explained. “It’s still this one neighborhood that’s gonna be like (expletive) this neighborhood. Like, it's gonna happen. This is just the latest way they taunt each other.”

His point is the neighborhoods’ core issues involving violence in D.C. need to be addressed before the music videos.

“A young guy, that doesn't have a stable home or nowhere to go?” E asked. “Oh, my God. Can you imagine? That’s like... That's straight survival.”

Back in Anacostia Park, Lucille Leach pores over her son’s last accomplishments. He had just gotten a business license and a Commercial Driver’s License before he was killed.

“He was gonna be a trucker driver he told me,” she sighed. “He wanted to get out of how we were living.”

When asked whether she thinks the music videos have caused or accelerated the violence in D.C., Lucille said no. She felt it was just a different way for the neighborhoods to beef over conflicts that have gone on for decades.

To her, the core problems affecting D.C.’s violence are systemic and stem from poverty. To her, Antonio wasn’t caught up in violent music, he got caught in a neighborhood rivalry’s violent cycle.

She has a message for parents.

“Talk to your kids, and see what direction they go on in life and try to help them get them help,” she said. “To the children, please just stop. You could be the next one, and your mom had to bury you.”

Sign up for the Get Up DC newsletter: Your forecast. Your commute. Your news.

Sign up for the Capitol Breach email newsletter, delivering the latest breaking news and a roundup of the investigation into the Capitol Riots on January 6, 2021.