Marine Corps vet pays $30K of his own money to bring fallen brothers home

The Vietnam veteran was left to front the bill for months when government money temporarily dried up.

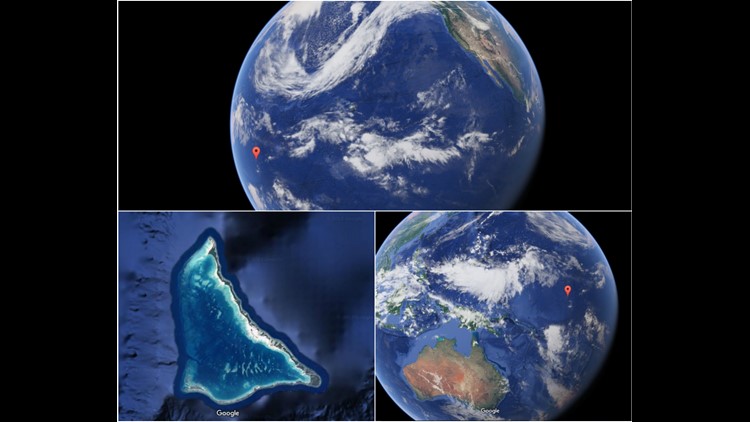

On a South Pacific island where the wounds of war mar majestic beaches, 444 Americans from World War II are still missing, buried under sand or claimed by the lagoon.

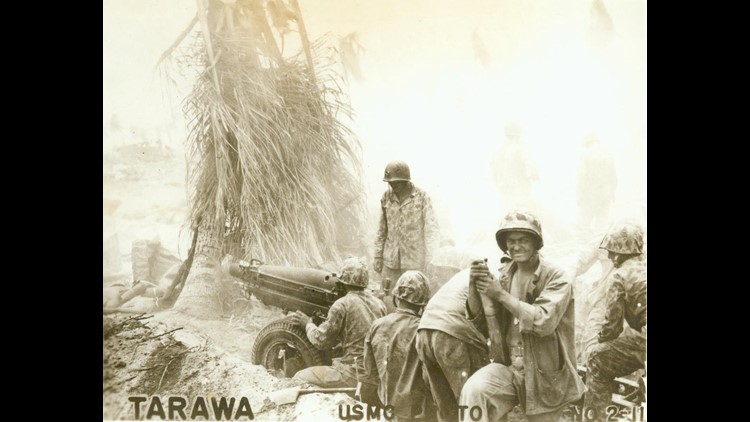

The phrase “no one left behind” is tested here on Tarawa, like nowhere else.

Remains of American dead from November 1943 are still found today on the secluded Pacific atoll, a world away from the dignified marble graves of Arlington National Cemetery.

Skeletons are unearthed near scenes of staggering poverty, feet from pig pens, and in some instances, left in repose under garbage.

The Battle of Tarawa was fought on a sandbar the size of the National Mall, 7,000 miles from Washington, D.C. The U.S. declared victory in three days, after a Japanese admiral boasted it would take a century to conquer the island.

But 74 years after nearly 1,000 U.S. troops lost their lives on Tarawa, the Americans of our time face fading memories and significant sacrifices tied to the challenges of finding the fallen.

In late 2017, a Marine Corps veteran poured tens of thousands of dollars of his own money into the effort in order to pay the anthropologists who unearth the lost remains of Tarawa.

The Vietnam veteran was left to front the bill for months when government money temporarily dried up.

The funding frustrations are traced back to the defense sequester of 2013, with the Pentagon at one point forced to cut more than a third of its MIA recovery operations.

The drawback impacted a valuable mission, with previously unreported data revealing Tarawa yields the most success in terms of finding American remains overseas.

The passage of the $1.3 trillion omnibus spending bill in March now offers renewed optimism, with an influx of money to Tarawa secured for one year.

But with the Battle of Tarawa largely faded from the public consciousness and prioritized below other pressing defense recovery missions, the Americans who return to the island continue the tenuous task of unearthing fallen brothers, left behind for two generations.

Graves Are Gone

The graves of Marines, sailors and airmen eluded discovery on Tarawa for decades, simply because all above-ground evidence of their existence is gone.

Troops who lost their lives were buried quickly – there was little time to return their bodies to Arlington, or to their hometowns, during a time of war.

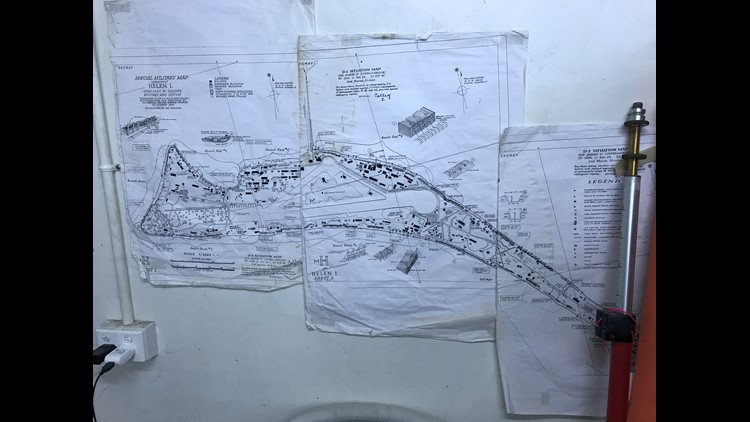

Defense Department documents reveal it was always the nation’s intent to find the war dead placed in shallow burial trenches when peace returned to the Pacific.

But only half the buried Americans were found in the years immediately after the war.

Aerial photographs and archival footage reviewed by WUSA9 show grave markers were removed by Navy construction crews by January 1944, all in an effort to rebuild the island’s decimated airbase.

An area of Tarawa identified as Cemetery 27 had all burial markers cleared, with roads and cargo placed over the graves. The setting still serves as a parking lot today, with the American non-profit known as History Flight excavating the remains of dozens of Marines under the pavement in 2015.

The non-profit continues to maintain the only American presence on the island devoted to finding the fallen.

PHOTOS: Tarawa past and present

Sacrifices, 74 Years Later

Retired Marine Corps Sgt. Glenn Prentice serves as History Flight’s vice president. He returned to Tarawa in March for his 20th trip to the island.

Prentice was back on the remote atoll to oversee the transfer of a full skeleton and bone fragments found by History Flight to the U.S. government. The Marine Corps sent a long-range C-20 aircraft to retrieve the remains, flying them to Hawaii and then to Dover Air Force Base for DNA testing.

But after the detachment of Marines loaded two flag-draped caskets into the aircraft, the financial cost of the homecoming slowly became apparent.

Bank records show Prentice spent $30,000 to fund History Flight’s operations from November 2017 – March 2018, money that largely came from Prentice’s own V.A. disability payments.

Records indicate the Department of Veterans Affairs sends the retired Marine Corps sergeant close to $39,000 annually. Prentice described the payments as normally used to treat PTSD from Vietnam and other combat injuries.

“It was money I simply needed to divert to History Flight, right now,” Prentice said in an interview. “Our employees weren’t getting paid, some people missed their house payments, and of course, the excavation work stopped.”

A review of public records and data compiled on GovTribe, a website for government contract analysis, shows History Flight experienced at least three gaps in federal funding since September 2015.

It was a trickle-down effect, after the arm of the Pentagon known as the Defense POW / MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) saw its budget cut from 2015 until April of this year.

In a June 2017 interview, the agency’s top official said the defense sequester immediately impacted DPAA, with funding falling from $127 million in 2015 to $112 in 2017.

“We took a dip of about 35 percent of our operations, we had to cut,” said Col. Fern Sumpter Winbush, then serving as acting director of DPAA until September 2017. “That was just the reality.”

PHOTOS: Excavating WWII servicemembers on Tarawa

The cuts also limited federal dollars sent to Tarawa, at a time when recoveries on the island began to show the most promise of any location overseas.

Defense data show Tarawa returned 32 sets of identified American remains in fiscal year 2017, followed by 27 returned from North Korea and 15 from South Korea.

Nine sets of remains came from areas involved in the Vietnam War, including Laos and Cambodia.

Cautious Optimism

Congressional action spurred a chain reaction in March, beginning with the approval of the nation’s largest defense budget in history.

DPAA reported funding through September now stands at $146.3 million, a record for the agency.

Weeks after his visit to Tarawa, Prentice received full reimbursement for the $30,000 transferred to History Flight. Records show the non-profit now has a government contract for $1.7 million extending through the end of the year.

“The picture was very uncertain because we had to make contingency plans, also look at private donations, making it very difficult and frustrating at times,” Prentice said.

“But it’s all part of the job, and we’re thrilled now. It’s simply the small price we pay to make sure no one is left behind.”