WASHINGTON — When Cindy Daily and her partner decided to have a baby in the early 2000s, they knew it wouldn't be an easy path. After using a sperm donor and going through several rounds of IVF, their baby boy Zack Daily-Anderson was finally born.

Daily bought donor sperm from the Fairfax Cryobank in Virginia, one of the largest sperm banks in the country.

"It's a long process," Daily said. "We printed out the catalog and started looking at donors who looked like me or my family."

When Daily-Anderson was still a child, his mother heard about the "Donor Sibling Registry," a website that keeps track of and connects children who share the same sperm donor. Through the DSR, Daily was able to find a handful of her son's half siblings. The families formed a bond over their unique situation and on occasion, even vacationed together.

"We started out with five to seven families at the beginning and then it seemed to grow exponentially," she said.

That growth came with the popularity of DNA sites like Ancestry.com and 23andMe causing their donor group number to skyrocket. Today, at 18-years old, Daily-Anderson has 237 half brothers and sisters that he knows of. Some live near him in Virginia, but others are spread out across the United States and the world. According to the family, all the siblings are linked to the same man who donated his sperm over many years.

During an interview in her Winchester, Virginia home, Daily said her family doesn't want to sensationalize their story, but wants to see some regulations in the industry that allowed their family to form.

"I think we need to take a step back, and the industry needs to step back and look at why are you allowing 230 some births to happen," Daily said.

Now a high school senior, Daily-Anderson has a relationship with some of his half siblings, but for many of the families, knowing how big their group has gotten has become too overwhelming.

"It's cool on a smaller scale, but when it gets to a larger scale, like our group, it's a bit worrisome," Daily-Anderson said.

Daily and her son said they don't want people to focus so much on the size of their donor family, but more on the lack of oversight in the fertility industry.

"You have a government that regulates us to death, but this is a loophole that they’ve never investigated," she said.

Their situation is one of many that highlights just how complicated the fertility industry is in the United States.

"The U.S. fertility industry, in terms of lack of regulation, has been called the 'Wild West,'" said Naomi Cahn, a family law professor at the University of Virginia.

There are few laws or limits set by the U.S. government, only guidelines. Those guidelines come from the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. The organization's detailed publication suggests sperm donors be at least 21 years old, recommends both donor and recipient counseling and also urges banks to set a limit of 25 births per donor. But ultimately, there is no oversight and no enforcement of the guidelines.

"At a minimum, we need to know the number of children conceived each year through donor sperm," Cahn said.

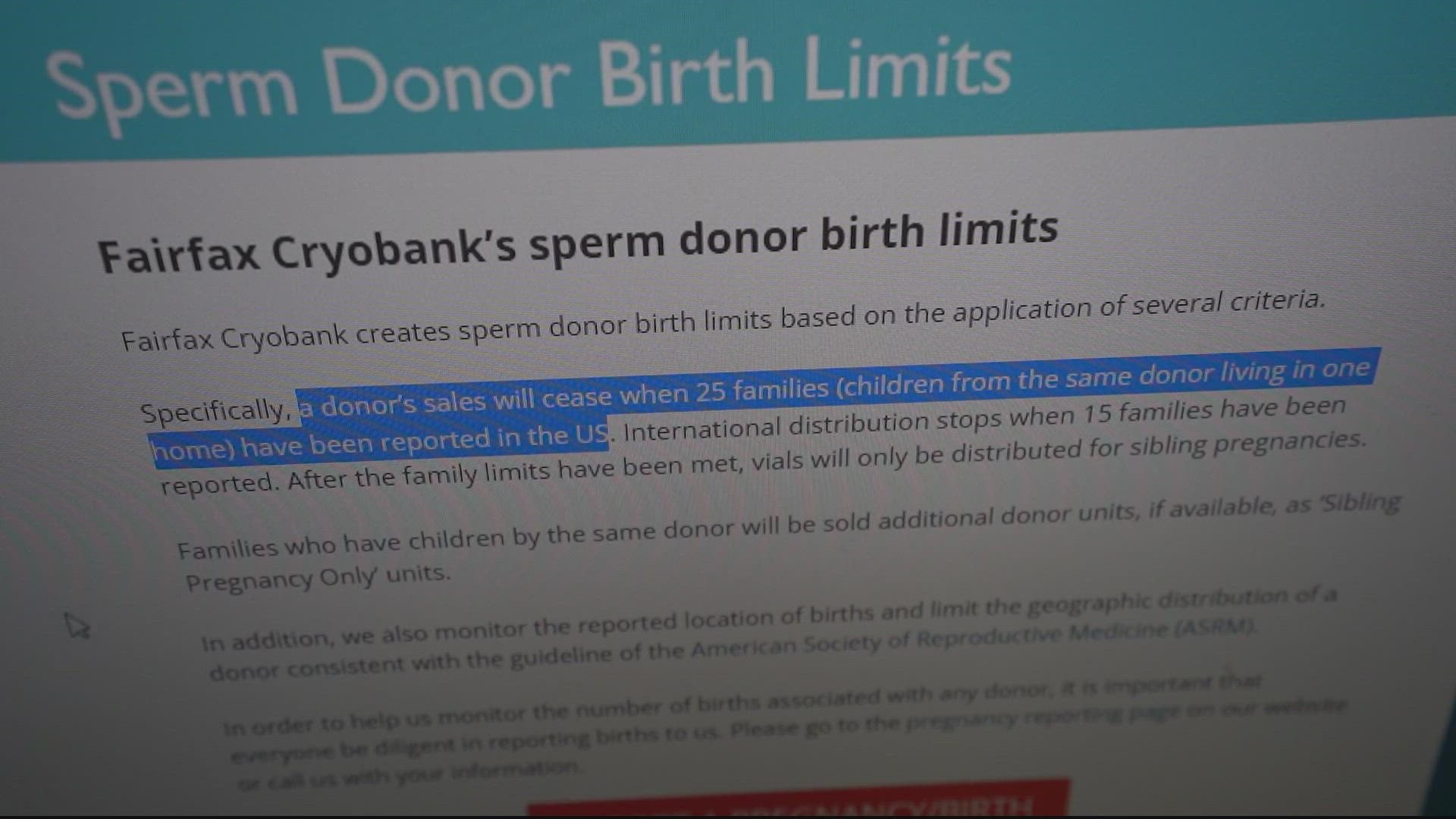

On Fairfax Cryobank's website, where Daily received her donor sperm, those guidelines are listed out clearly. The sperm bank, which declined WUSA9's request for an interview, states that in the U.S., a donor's distribution will stop when 25 families using the same donor have been reported. Internationally, their donor distribution will cease when 15 families using the same donor have been reported.

But even if a bank follows those guidelines, there's no limit on how many different places a donor can go to donate.

The U.S. Donor Conceived Council is a newly formed nonprofit organization that works to advocate for the needs of donor-conceived people.

"The voice of donor-conceived people up until this point hasn’t been heard," Tyler Sniff, the vice president of legal affairs at the U.S. Donor Conceived Council said.

Sniff discovered he was donor-conceived at 32 years old after taking a DNA test he received as a gift. With the use of DNA sites on the rise, donor anonymity is not guaranteed like it was decades ago.

On May 10, lawmakers in Colorado passed a new law that advocates say is the first of its kind in the nation. Starting in 2025, Colorado will no longer allow anonymous sperm and egg donations, meaning when a donor-conceived person turns 18, they would have access to their genetic donor's identity. The child and their family would also have access to the donor's medical information before the age of 18.

"We can't guarantee anonymity," one of the sponsors of the bill, Colorado Rep. Kerry Tipper (D), said. "It's very disruptive to donors' lives 18 years down the road to be contacted by some children, or a lot of children, that are genetically theirs. It's disruptive to their lives, as well as the donor-conceived children that didn't know. This is really best practice for both sides."

The new law also enforces the minimum age of 21 for all donors, and requires egg and sperm banks to keep strict records to make sure no donor is used for more than 25 families in and out of state. This law, however, does not impact the number of siblings that can be born to one family.

Some lawmakers who voted against the bill voiced concerns about the negative impact this law might potentially have on the number of donors still willing to donate if anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

While groundbreaking, this law only impacts one state. Advocates hope to keep pushing for an impact on a larger scale.

"It hopefully provides a template for other states to consider changing their approaches to donor conception," Cahn said.

Daily and her son said that despite their family situation, life is very normal for them. But they hope that something can be done to prevent large donor groups like theirs from happening in the future.

"I think we made the best of it, but I’d like other people not to have to go through that," Daily said. "Keep it small, keep it simple."