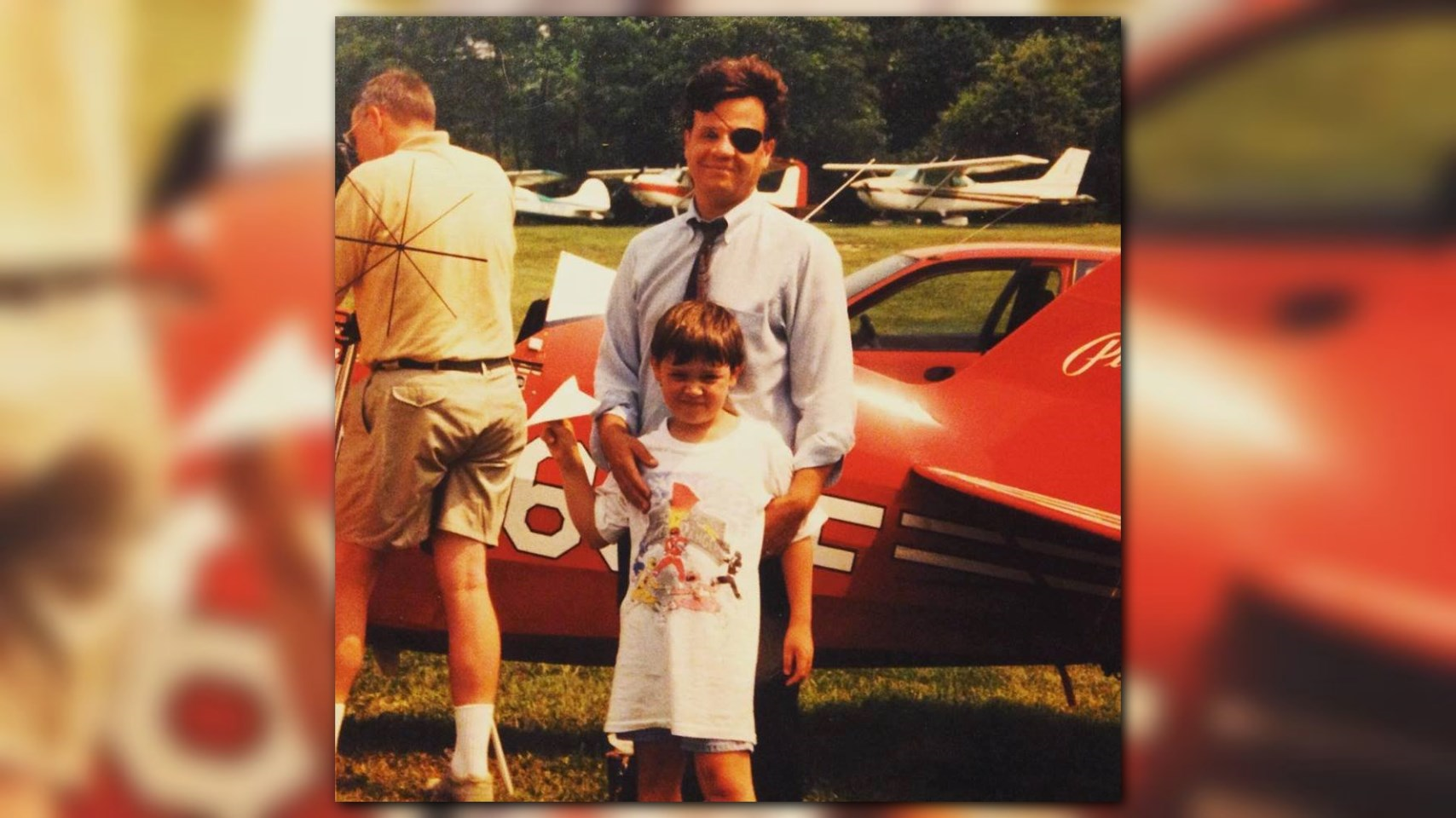

My dad’s brain cancer diagnosis was like taking down Ali in his prime. In just five years, he made a miraculous recovery from a plane crash that took his left eye, learned to fly again, sold his successful business, and started a new one. He was confident—with a ponytail and an eyepatch.

He was 42 years old. I was ten.

While visiting California for an aviation trade show, my dad stood up in our hotel room, clutched his forehead, and fell to the ground in pain. I called 911.

I remember doctors telling my mother that they not only found brain bleeding, but a rare kind of brain tumor. “Gleeo-what,” my mother said, trying to understand the diagnosis. My father’s life expectancy? 12 months, maybe longer.

Over the next few months, my mother and I became all too familiar with glioblastoma— called an “orphan disease” by doctors due to its rarity. About 13,000 people die from it every year. Compare that to lung cancer, which the American Lung Association kills about 150,000 every year. It has afflicted notable Americans—Senator Ted Kennedy, Vice President Joe Biden’s son Beau, and now Senator John McCain. When news of their diagnoses broke, I—not a religious person—prayed for them. Glioblastoma is grisly.

In 1999, the treatment was as aggressive as the disease. My dad underwent a pair of surgeries. He got radiation treatments at Johns Hopkins Medical Center and chemotherapy at Duke University. He smoked marijuana to help with the side-effects. My late mother, also a pilot, flew my father to visit the country’s leading glioblastoma researchers, sometimes showing up unannounced. This earned entry in two clinical trials. But it wasn’t enough.

Around the New Year, my dad’s speech slowed and the left side of his body slumped. My mother and I pushed him in a wheelchair. In July 2000, he slipped into a coma. He took his last breaths early in the morning of August 17. I remember being relieved that my father—a man of action—was no longer bound to a hospice bed.

Doctors argue that glioblastoma is not a death sentence.

“There’s an ever increasing minority who survive,” said Dr. Henry Friedman, who saw my father at Duke University. His aggressive research includes infecting the tumor with polio—a virus that killed for centuries.

“I have great respect for Senator McCain,” said Friedman. “I think what is pivotal is your will to be successful at a patient and institutional level.”